Difficulties related to communication are among the earliest symptoms of dementia and tend to worsen as the disease progresses. Difficulty with word finding, replacing a word with an unrelated word, or not finding a word at all often occurs in the early stage. As the disease progresses, forgetting names of family members and friends, confusion about family relationships, and loss of the ability to recognize family members is not uncommon.

Losing the ability to communicate is embarrassing, frustrating, and stigmatizing. Needs go unmet and social interactions gradually become more stressful and tiring. Being unable to communicate needs and preferences can lead to conflicts and depression and make communication more difficult for caregivers.

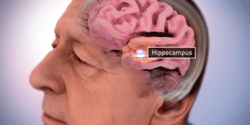

Location of the hippocampus. Source: Image courtesy of the National Institute on Aging/National Institutes of Health. Public domain.

In Alzheimer’s, damage to the hippocampus affects the formation of new, short-term memories. This means a person does not remember the “what, where, and when” of recent events—what they ate yesterday, where they went 2 days ago, and the date of their next doctor’s appointment.

In frontal-temporal dementia, damage begins in the front part of the brain. Because of the location, memory is (initially) less affected than in Alzheimer’s disease. This is because the front part of the brain is responsible for judgment, planning, moral reasoning, logical thinking, and social behavior. As a result, a person may become more impulsive, make sexual comments or socially inappropriate remarks, and gradually lose the ability to make decisions.

In vascular dementia, damage is caused by impaired blood flow to the brain. Cognitive changes can be widespread and not necessarily associated with a specific part of the brain. There may be a slowness of thought, problems with attention and concentration, and difficulties with language. Complex, fast-paced conversations or quick changes in topic may be difficult to follow.

In Lewy body dementia, abnormal clumps of alpha-synuclein (Lewy bodies) form throughout the cerebral cortex, brainstem, and midbrain. The location influences the symptoms, which vary from person to person. A person with Lewy Body dementia can experience paranoia, delusions, and hallucinations (usually visual), which are very real for the person experiencing them.

6.1 Areas of Brain Associated with Communication

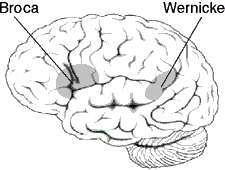

Certain parts of the brain are responsible for speech and language, mainly located in the left side of the brain. These brain regions and their connections form a network that provides the hardware for language in the brain. Without this network, we would not be able to talk to or understand others (Brauer, 2014).

The loss or decline of language and communication skills is called aphasia. This is an acquired language disorder that affects a person’s ability to comprehend and produce language. People with aphasia have trouble expressing themselves, finding the right words, understanding the words they are hearing—and also, have difficulty with reading and writing. Aphasia is a common symptom in a person with a stroke that affects the left side of the brain.

Wernicke’s aphasia is caused by damage to the left temporal lobe. It is sometimes referred to as fluent aphasia because a person can speak but the words carry no meaning. Broca’s aphasia is caused by damage to the left frontal lobe. It is sometimes referred to as non-fluent aphasia because a person’s speech is short and choppy. Global aphasia is a combination of Wernicke’s and Broca’s aphasia in which a person is unable to understand the spoken word or communicate with speech.

Speech and Language Areas of the Brain

Left: Areas of the left side of the brain associated with processing speech and language. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Used with permission. Right: Broca’s and Wernicke’s brain regions are highlighted in red and orange. The blue and green lines illustrate connections that link the two regions with one another and form a network of language areas. Frontiers for Young Minds. Reprinted with permission.

Communication and emotions are related. An area of the brain located close to the hippocampus called the amygdala is involved with emotions, particularly emotional behavior, learning, and motivation. Damage to this part of the brain can affect a person’s ability to read facial emotions as well as their ability to control their own emotions. Damage to the amygdala can affect a person’s ability to understand when another person is frustrated, angry, or even happy. This likely affects a person’s ability to follow non-verbal facial cues.

6.2 How Dementia Affects Communication

Dementia affects our ability to communicate, as well as our ability to comprehend what others are trying to communicate. A person with dementia may (Alzheimer’s Society of Canada, 2024):

- Create new words for ones that are forgotten.

- Repeat a word or phrase (perseveration).

- Have difficulty organizing words into logical sentences.

- Curse or use other offensive language.

- Revert to their original language.

- Talk less than usual.

6.3 Managing Communication Challenges

Caregivers may not understand that, for a person with dementia, difficulties with communication increase a person’s confusion and stress. For caregivers and healthcare providers, the ability to communicate effectively and successfully with people impaired by cognitive decline is a learned skill.

Techniques that improve communication and reduce agitation, confusion, fear, or anxiety include (Zeman, 2015):

- Approaching from the front or side and sitting or kneeling at eye level.

- Assessing your client’s body language.

- Monitoring your own body language, facial expression, and tone of voice.

- Introducing yourself each time and explaining what you are doing and why.

- Making sure the person with dementia can clearly see you.

- Reducing distractions.

- Speaking slowly and clearly using short sentences.

- Allowing extra time for a response.

Communication habits to be avoided include:

- Standing over or speaking “down” to a person

- Using words such as: “she’s just like a baby” or “he’s the same as my 2-year-old”

- Talking in complex or lengthy sentences

- Speaking quickly

- Using an impatient voice

- Failing to allow the person with dementia enough time to process what you are trying to communicate

- Rushing through any activity

Hallie Is Scared

Introduction: As many as two-thirds of stroke patients experience cognitive impairment or cognitive decline following a stroke; approximately one-third go on to develop dementia. This may be inadvertently overlooked because, following a stroke, the emphasis is often on recovery of functional abilities such as walking and activities of daily living.

Client Information: Hallie is a 90-year-old woman who moved from Phoenix to live with her daughter in Miami, Florida following a brainstem stroke. She is struggling with mobility and also has difficulty expressing her needs. She refuses to participate in any activities.

Prior to suffering the stroke, she lived independently in Mesa, Arizona with her alcoholic son. In the hospital following the stroke, she was given a feeding tube due to swallowing problems. When she arrived in Florida, she was able to walk a few steps with a walker but needed a great deal of assistance with transfers, toileting, and bathing. For more than a year after moving she was unable to name the town or even what state she was living in. She was, however, able to read and write and her vision was good enough to read the captions on the TV.

Now, almost 2 years after her stroke, Hallie is off her feeding tube, eating independently and enthusiastically, coloring intricate patterns in a coloring book. She is transferring and bathing with much less assistance. She is still unable to walk more than few steps and has difficulty with memory and recall.

Timeline: Because of her improvement, Hallie’s daughter feels her mother might enjoy the local specialized adult daycare program. The first time they attend, Hallie was withdrawn and refused to participate in any activities—even drawing. The activities director, Celena, tried to engage Hallie in a conversation but she just smiled and asked where her mother is. Celana asked Hallie to tell her about her mother, but she didn’t (or couldn’t) answer.

When Hallie’s daughter came to pick up her mom, the daycare center administrator reported that Hallie didn’t participate in any activities and wouldn’t budge from her recliner—even to use the bathroom. The activities direct feels that, with some gentle encouragement, Hallie will begin to participate in activities. She reported her observations and concerns to the facility administrator.

Intervention: The staff discussed Hallie’s situation after the center closed that afternoon. The administrator asked Jeni, a registered nurse, to assess Hallie in the morning—to spend some time with her and try to draw her out. Hallie’s daughter is also a nurse, and the administrator thinks that Hallie may be comfortable talking to a nurse. When Hallie arrives the next day, Jeni, using her dementia-specific training, approaches Hallie from the front, introduces herself, sits beside her, and offers her hand, which Hallie takes. She asks about Hallie’s daughter and says that she too is a nurse. She tries to engage Hallie in a general conversation, but without success.

Hallie is very quiet and seems confused. She asks Jeni where she is and again asks for her mother. Jeni makes sure Hallie is comfortable, quietly assesses her hearing and vision, and makes sure Hallie is able to understand English. Finally, after some quiet back and forth, Hallie admits that she’s scared. Jeni asks her why and she says she is scared because she can’t remember things. This provides staff with the information they need to design activities that will help Hallie feel more comfortable at day care.

Discussion: It is normal for a person to feel uncomfortable in a new social situation. This is especially true for a person with memory problems. Hallie is new to adult daycare, in a new living situation, and new to Florida. The transition has been difficult for her. The staff acknowledge Hallie’s fears and make sure to support and educate Hallie’s family caregivers.

Hallie has many positive things going for her, considering the severity of her stroke. Her vision is good, she has a good sense of humor, she enjoys drawing, and she eats just about anything you put in front of her. Staff members learn that Hallie isn’t fond of physical activity but is able to concentrate on her intricate drawings for long periods of time. She also likes TV. They design a program of activities that focuses on art, drawing, and painting. They encourage her to participate in the exercise class, which she does reluctantly. Eventually, the activities director realizes that Hallie does better with one-on-one exercise.

Client Perspective: Hallie tells her daughter that she doesn’t want to go to “that place” although she isn’t able to articulate what she means. Her daughter encourages Hallie to go again, telling her that they are having hamburgers for lunch. Hallie says she is OK with that and agrees to attend adult daycare again.