Certain pain syndromes are pervasive. Low back pain, migraine headaches, post operative pain, cancer pain, and pain associated with arthritis are some of the most common reasons patients seek medical care for pain.

Low Back Pain

Low back pain affects approximately 80% of people at some stage in their lives. If low back pain becomes chronic it often results in lost wages and additional medical expenses and can increase the risk of incurring other medical conditions (Chou et al., 2016).

In the United States, the total indirect and direct costs due to low back pain are estimated to be greater than $100 billion annually (Wang et al., 2012). It is the fifth most common reason for all physician visits. Approximately one-quarter of U.S. adults reported having low back pain lasting at least 1 day in the past 3 months, and more than 7% reported at least one episode of severe low back pain in the previous year.

Clinically, the natural course of low back pain is usually favorable; acute low back pain frequently disappears within 1 to 2 weeks. Any of the spinal structures, including intervertebral discs, facet joints, vertebral bodies, ligaments, or muscles could be an origin of back pain, which is, unfortunately, difficult to determine. In those cases in which the origin of back pain cannot be determined, the diagnosis given is nonspecific low back pain (Aoki et al., 2012).

Assessing Low Back Pain

The vast majority of low back pain patients who present to primary care have pain that cannot be reliably attributed to a specific disease or spinal abnormality. Spinal imaging abnormalities such as degenerative disc disease, facet joint arthropathy, and bulging or herniated intervertebral discs are extremely common in patients with or without low back pain, particularly in older adults, and such findings are poor predictors for the presence or severity of low back pain (Chou et al., 2016).

Low back pain symptoms can arise from many anatomic sources, such as nerve roots, muscle, fascia, bones, joints, intervertebral discs, and organs within the abdominal cavity. Symptoms can also be caused by aberrant neurologic pain processing, a condition called neuropathic low back pain. The diagnostic evaluation of patients with low back pain can be challenging and requires complex clinical decision-making. Nevertheless, the identification of the source of the pain is of fundamental importance in determining the therapeutic approach (Allegri et al., 2016).

The location of pain, frequency of symptoms, duration of pain, history of previous symptoms, previous treatments, and response to treatment should be assessed. The possibility of low back pain due to pancreatitis, nephrolithiasis, or aortic aneurysm, or systemic illnesses such as endocarditis or viral syndromes, should also be considered. Low back pain can be influenced by psychological factors, such as stress, depression, or anxiety. History should include substance use exposure, detailed health history, work habits, and psychosocial factors (Allegri et al., 2016).

Back pain can be referred or felt at a site distant from the source of the pain. Pain can be local or referred from a painful stimulus occurring in and internal organ. An example of referred pain is when a heart attack occurs and pain in felt in the jaw, shoulder, or arm.

Pain may also be felt in the area or region within the territory of a dermatome, an area of skin supplied by a single sensory nerve. This is referred to as radiating pain and can be quite confusing for patients. If the nerve root is irritated or inflamed, pain can be evoked by any motion that stretches or compresses the root of the nerve; this is referred to as radicular pain, which can occur in patients with serious or progressive neurologic deficits or underlying conditions requiring prompt evaluation, as well as patients with other conditions that may respond to specific treatments.

Patients with back and leg pain have a fairly high sensitivity for herniated disc, with more than 90% of symptomatic lumbar disc herniation occurring at the L4/L5 and L5/S1 levels. A focused examination that includes straight leg–raise testing and a neurologic examination that includes evaluation of knee strength and reflexes (L4 nerve root), great toe and foot dorsiflexion strength (L5 nerve root), foot plantar flexion and ankle reflexes (S1 nerve root), and distribution of sensory symptoms should be done to assess the presence and severity of nerve root dysfunction.

Imaging tests such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be considered only in the presence of clinical elements that are not completely clear or in the presence of neurologic deficits or other medical conditions. The recommendation of the American College of Radiology is not to do imaging for low back pain within the first 6 weeks unless red flags are present. Red flags include recent significant trauma or milder trauma at age older than 50 years, unexplained weight loss, unexplained fever, immunosuppression, history of cancer, intravenous drug use, prolonged use of corticosteroids, osteoporosis, age older than 70 years, and focal neurologic deficits with progressive or disabling symptoms (Allegri et al., 2016).

Treating Low Back Pain

In Oregon changes to the Oregon Health Plan/Prioritized List of Health Services, effective July 1, 2016, have expanded coverage for the assessment and conservative treatment of uncomplicated back pain and conditions. Previously, the OHP has limited treatment to patients with muscle weakness or other signs of nerve damage. Beginning in 2016, treatments will be available for all back conditions. Before treatment begins, providers will assess patients to determine their level of risk for chronic back pain, and whether they meet criteria for a surgical consultation (OHA, 2016).

Based on the results, one or more of the following covered treatments may be appropriate:

- Acupuncture

- Chiropractic manipulation

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (a form of talk therapy)

- Medications (including short-term opiate drugs, but not long-term prescriptions)

- Office visits

- Osteopathic manipulation

- Physical and occupational therapy

- Surgery (only for a limited number of conditions where evidence shows surgery is more effective than other treatment options) (OHA, 2016)

In addition, yoga, intensive rehabilitation, massage, or supervised exercise therapy are now recommended to be included in the comprehensive treatment plans. These services, which also have evidence of effectiveness, will be provided where available as determined by each Coordinated Care Organization (CCO) (OHA, 2016).

Interventional Pain Management Techniques

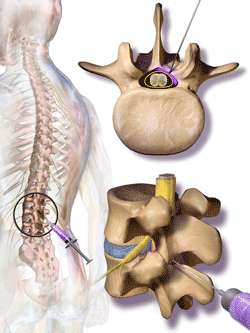

Interventional techniques are minimally invasive procedures that place drugs in targeted areas or ablate target nerves. This category includes epidural injections as well as some surgical techniques such as laser or endoscopic discectomy, intrathecal infusion pumps, and spinal cord stimulators, used for the diagnosis and management of chronic, persistent, or intractable pain (Manchikanti et al., 2010).

Steroids are injected into the cerebrospinal fluid in the canal surrounding the spine. Nerves branch out from the spine. The nerve roots, which may be compressed, are at the base of the nerves. Source: Blausen.com staff. “Blausen gallery 2014.” Wikiversity Journal of Medicine.

Epidural injections, in which steroids and anti-inflammatories are injected directly into the epidural space of the spinal cord, are the most commonly performed procedures in interventional pain management, comprising 46% of all interventional techniques. The most commonly performed procedures are lumbosacral interlaminar or caudal epidural injections. Facet joint interventions are the second most commonly performed procedures, constituting 38% of all interventional techniques in 2011 (Manchikanti et al., 2010).

Analysis of various spinal interventional techniques indicates that there has been an overall increase in interventions of 177% per 100,000 in the Medicare fee-for-service population, with the highest increases seen for sacroiliac joint injections at 331%, facet joint interventions at 308%, and epidurals at 130% (Manchikanti et al., 2013). A systematic review of interventional therapies for low back and radicular pain concluded: “Few nonsurgical interventional therapies for low back pain have been shown to be effective in randomized, placebo-controlled trials” (IOM, 2011).

Although interventional techniques are often considered to be surgical procedures, more invasive procedures such as joint replacement, spinal fusion, and disc replacement are also commonly and successfully used to relieve pain. These types of surgeries often occur after other conservative treatments have failed to relieve the pain.

Migraine Headaches

A migraine is a painful headache thought to result from vasodilation of blood vessels in the brain. Migraines cause intense, pulsing or throbbing pain on one or possibly both sides of the head. People with migraine headaches often describe pain in the temples or behind one eye or ear. Migraine sufferers may have symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and sensitivity to light and sound. Some people see spots or flashing lights or have a temporary loss of vision that forewarn of an impending headache. If a migraine occurs more than 15 days each month for 3 months, it is considered chronic.

Numerous imaging studies of migraine patients have described multiple changes in brain functions as a result of migraine attacks; these include enhanced cortical excitability, increased gray matter volume in some regions and decreased in others, enhanced brain blood flow, and altered pain modulatory systems (Maleki et al., 2011).

Migraine has no current cure. Drug therapies are broadly divided into two groups: (1) those designed to treat acute occurrences, and (2) those that are prophylactic (preventive) in nature. Many people who have migraines use both forms of treatment. The goal is to treat migraine symptoms as soon as possible and to minimize the number of migraine occurrences by avoiding triggers.

Post Operative Pain

In the United States, nearly 100 million surgeries take place annually—about 46 million inpatient and about 53 million outpatient procedures. Post operative pain is often underestimated and undertreated, leading to increased morbidity and mortality, mostly due to respiratory and thromboembolic complications, increased hospital stay, and impaired quality of life (EAU, 2013).

Post operative pain is common and can be caused by tissue damage, the presence of drains and tubes, post operative complications, prolonged time in an awkward position, or a combination of these factors. Good post operative pain management requires good pain assessment and measurement in all post operative patients. Assessment should focus on the patient’s response to surgery as well as respiratory and cardiac complications. It should occur at scheduled intervals, in response to new pain, and prior to discharge (EAU, 2013).

Although much of the focus on post operative pain management is in hospitals, about 60% of surgical procedures in community hospitals are performed on an outpatient basis, and persistent problems exist with pain management after discharge (IOM, 2011). This may be because there is not enough time to assess post surgical pain prior to discharge or to establish a pain management program at home.

Psychological factors such as anxiety and depression can be important predictors in the development of post operative pain. Age has also been found as a predictor, with younger individuals being at higher risk for moderate to intense pain. Patients at high risk for severe post operative pain should be provided with special attention. Patients with good analgesia are more cooperative, recover more rapidly, and leave the hospital sooner. They also have a lower risk for prolonged pain after surgery (Ene et al., 2008).

Post operative pain that continues for more than 2 months and cannot be explained by other causes is referred to as persistent post surgical pain (Kehlet & Rathmell, 2010). About 10% to 50% of post operative patients develop persistent pain following common surgical procedures such as groin hernia repair, breast and thoracic surgery, leg amputation, and coronary artery bypass surgery, often due to nerve damage during the procedure (IOM, 2011).

Persistent post operative pain is a serious clinical problem. The factors that seem to affect its incidence include the extent of preoperative pain, trauma during surgery, and anxiety and depression. Cancer patients are particularly susceptible. Comorbidity of pain and depression provokes worsening of both conditions (Ghoneim & O’Hara, 2016).

To identify the scope of a person’s pain following surgery, especially pain persisting more than 2 to 3 months, a careful clinical evaluation is needed. This includes history, physical examination, and appropriate special tests in order to identify or exclude reversible underlying conditions (Gilron & Kehlet, 2014). Be aware of risk of persistent pain following surgery in the following instances:

- If the patient was previously pain free but has now developed a new chronic pain syndrome

- If previous pain at the site of surgery still remains

- If the patient previously suffered from a chronic pain syndrome—unrelated to the surgery—and the pain persists (Gilron & Kehlet, 2014)

In the ICU, most, if not all, patients will experience pain at some point during their ICU stay. Pain can be related to injury, surgery, burns, or comorbidities such as cancer, or from procedures performed for diagnostic or treatment purposes. Some patients may even experience substantial pain at rest. Despite increased attention to assessment and pain management, pain remains a significant problem for ICU patients (Kyranou & Puntillo, 2012).

Unrelieved pain in adult ICU patients is far from benign. Medical and surgical ICU patients who recalled pain and other traumatic situations while in the ICU had a higher incidence of chronic pain and post traumatic stress disorder symptoms than did a comparative group of ICU patients. Concurrent or past pain may be the greatest risk factor for development of chronic pain (Kyranou & Puntillo, 2012).

Pain Associated with Cancer

Pain occurs in 20% to 50% of patients with cancer (NCI, 2016). It is one of the most feared and common symptoms of a variety of cancers and is a primary determinant of the poor quality of life in cancer patients (Bali et al., 2013). Cancer-associated pain—particularly neuropathic pain—is often resistant to conventional therapeutics whose application may be severely limited due to side effects (Bali et al., 2013). In the advanced stage, moderate to severe pain affects roughly 80% of cancer patients. Younger patients are more likely to experience cancer pain and pain flares than are older patients (NCI, 2016).

Research from Europe, Asia, Australia, and the United States indicates that cancer patients are repeatedly undertreated for pain, both as inpatients and outpatients—sometimes receiving no analgesia at all. Regardless of what stage the cancer has reached, it is necessary to determine the prevalence of pain in specific cancer types, both to raise awareness among clinicians and to improve patient management (Kuo et al., 2011).

Breakthrough pain is common in cancer patients. It is a temporary increase or flare of pain that occurs in the setting of relatively well-controlled acute or chronic pain (NCI, 2016).

Incident pain is a type of breakthrough pain related to certain activities or factors such as vertebral body pain from metastatic disease. Breakthrough and incident pain are often difficult to treat effectively because of their episodic nature. In one study, 75% of patients experienced breakthrough pain; 30% of this pain was incidental, 26% was non-incidental, 16% was caused by end-of-dose failure, and the rest had mixed etiologies (NCI, 2016).

Pain can be a side-effect of therapies used to treat cancer. Pain is reported by 59% of patients receiving anti-cancer treatment and 33% of patients after curative treatments (NCI, 2016). Pain syndromes caused by cancer therapies include:

- Infusion-related pain syndromes (venous spasm, chemical phlebitis, vesicant extravasation, and anthracycline-associated flare)

- Treatment-related mucositis

- Chemotherapy-related musculoskeletal pain (diffuse arthralgias and myalgias in 10% to 20% of patients)

- Dermatologic complications and chemotherapy (acute herpetic neuralgia, tingling or burning in their palms and soles, rash)

- Pain from supportive care therapies (osteonecrosis, avascular necrosis)

- Radiation-induced pain (mucositis, mucosal inflammation in areas receiving radiation, pain flares, and radiation dermatitis) (NCI, 2016)

Clinical management of cancer pain is complex, driven by patient’s response, and the need to have both shorter and longer acting preparations and equi-analgesic dose ratios. The process of combining or switching opioids is complex for the clinician, who must understand the different half-life, receptors, and conversion ratios of these opioids, which can vary greatly among individuals, opioids, and even by opioid dose (Gao et al., 2014).

The Pain Ladder was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in the context of cancer care. The WHO three-step analgesic ladder presents a stepped approach based on pain severity. If the pain is mild, begin with Step 1. If pain persists or worsens, a change to a Step 2 or Step 3 analgesic is indicated. At each step, an adjuvant drug* or modality such as radiation therapy may be considered in selected patients (WHO, 2016).

*Adjuvant drugs: can enhance the analgesic effect of opioid drugs in patients with cancer. Concurrent use of adjuvants is recommended by the WHO and has been recognized as an effective strategy in improving the balance between analgesia and side effects. However, consistent evidence suggests an under-utilization of adjuvants in cancer pain management, which may contribute to unnecessary opioid switching or rotation (Gao et al., 2014).

World Health Organization Analgesic Ladder

Source: Adapted from WHO, 1986. Used with permission.

In general, analgesics should be given “by mouth, by the clock, by the ladder, and for the individual” and should include regular scheduling of the analgesic, not just on an as-needed basis. In addition, rescue doses for breakthrough pain should be added. Each analgesic regimen should be adjusted for the patient’s individual circumstances and physical condition (NCI, 2013).

Pain Associated with Arthritis

Arthritis and other rheumatic conditions are a leading cause of disability in adults in the United States. Negative consequences, including pain, reduced physical ability, depression, and reduced quality of life, can impact the physical functioning and psychological well-being of those living with these conditions (Schoffman et al., 2013).

Treatment of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions is costly, and given the growing number of people in the United States over the age of 65, these conditions are expected to be a large burden on the healthcare system in the coming years. The number of Americans with arthritis and other rheumatic conditions is expected to reach about 67 million by 2030 (25% of Americans) (Schoffman et al., 2013).

Osteoarthritis

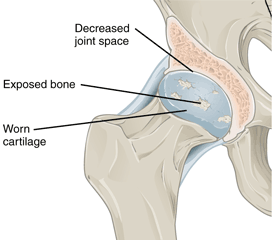

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a joint disorder characterized by degeneration of joint cartilage. Spurs grow out from the edge of the bone, and synovial fluid increases, causing stiffness and pain (NIAMS, 2015). With OA, joint pain and stiffness worsens over time. OA is the most common form of arthritis and affects close to 27 million Americans. After the age of 65, 60% of men and 70% of women experience OA (Van Liew et al., 2013).

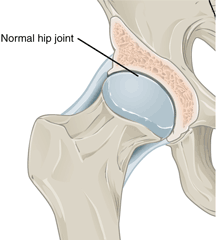

Hip Joint Showing Osteoarthritis Progression

Left: Normal hip joint. Right: Hip joint with osteoarthritis. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Osteoarthritis in Joints

Osteoarthritis most often occurs in the hands (at the ends of the fingers and thumbs), spine (neck and lower back), knees, and hips. Source: NIAMS, 2015.

Although the prevalence of osteoarthritis increases with age, younger people can also develop it, usually as the result of a joint injury, a joint malformation, or a genetic defect in joint cartilage. Before age 45, more men than women have osteoarthritis; after age 45, it is more common in women. OA is more likely to occur in people who are overweight and in those with jobs that stress particular joints. The joints most commonly affected by OA are those at the ends of the fingers, thumbs, neck, lower back, knees, and hips (NIAMS, 2015).

Best practice guidelines focus on self-management: weight control, physical activity, and pharmacologic support for inflammation and pain. Although low-grade inflammation underlies chronic osteoarthritis, it has not been a focus of best practice guidelines. Obesity is an independent risk factor for osteoarthritis and there is an interactive relationship among osteoarthritis, obesity, and physical inactivity (Dean & Hansen, 2012).

Physical exercise is widely recommended for individuals with OA. A meta-analysis on treatments for OA found that exercise programs reduced pain, improved physical functioning, and enhanced quality of life among individuals with OA (Van Liew et al., 2013). Despite this, close to 44% of adults with arthritis report not engaging in exercise.

Pain associated with osteoarthritis can lead to decreased physical activity, which is an independent risk factor for inflammation, likely due to the reduced expression of anti-inflammatory mediators. Physical inactivity also reduces daily energy expenditure and promotes weight gain (Dean & Hansen, 2012).

Psychological distress can adversely affect people with OA. Evidence suggests that anxiety and depression lead to reduced functioning and to lower levels of physical activity. Although depression may pose barriers to activity engagement, physical activity has been shown to improve its symptoms and is a common focus of behavioral therapies. Conversely, improvements in depression are also likely to lead to increases in activity levels and quality of life (Van Liew et al., 2013).

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is among the most disabling forms of arthritis and it affects about 1% of the U.S. adult population (about 2 million people). RA is an autoimmune disease that involves inflammation of the synovium, a thin layer of tissue lining the joint space. As the disease worsens, there is a progressive erosion of bone, leading to misalignment of the affected joint, loss of function, and disability. Rheumatoid arthritis tends to affect the small joints of the hands and feet in a symmetric pattern, but other joint patterns are often seen.

Because of its systemic pro-inflammatory state, RA can damage virtually any extra-articular tissue. Cardiovascular disease is considered an extra-articular manifestation and a major predictor of poor prognosis. Traditional risk factors such as obesity, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, hypertension, physical inactivity, advanced age, male gender, family history of cardiovascular disease, hyperhomocysteinemia, and tobacco use have been associated with cardiovascular disease in RA patients. In fact, seropositive RA may, like diabetes, act as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (Sarmiento-Monroy et al., 2012).

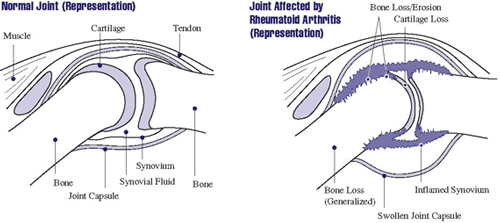

Joint Affected by Rheumatoid Arthritis

In rheumatoid arthritis, the synovium becomes inflamed, causing warmth, redness, swelling, and pain. As the disease progresses, the inflamed synovium invades and damages the cartilage and bone of the joint. Surrounding muscles, ligaments, and tendons become weakened. Rheumatoid arthritis can also cause more generalized bone loss that may lead to osteoporosis (fragile bones that are prone to fracture). Source: NIAMS, 2016.

Women are nearly three times more likely than men to develop rheumatoid arthritis—it can start at any age (mean age at the onset is 40 to 60 years). The precise cause of rheumatoid arthritis is unknown; like other autoimmune diseases it arises from a variable combination of genetic susceptibility, environmental factors, and the inappropriate activation of the immune responses. Multiple genes are associated with disease susceptibility, with the HLA locus accounting for 30% to 50% of the overall genetic risk (Fattahi & Mirshafiey, 2012).

Studies that explore the role of pain as a predictor of functional disability typically focus on concurrent pain, or treat pain as a variable when examining predictors of future function. Since factors other than pain are the main predictors of interest, these studies fail to fully characterize the association of pain with future function and, more important, do not explore how different measures of pain and the time periods they reference may impact results (Santiago et al., 2016).

Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is an inflammatory joint disease characterized by stiffness, pain, swelling, and tenderness of the joints, as well as the surrounding ligaments and tendons. It affects men and women equally, typically presents at the age of 30 to 50 years, and is associated with psoriasis in approximately 25% of patients. Cutaneous disease usually precedes the onset of psoriatic arthritis by an average of 10 years in the majority of patients but 14% to 21% of patients with psoriatic arthritis develop symptoms of arthritis prior to the development of skin disease. The presentation is variable and can range from a mild, nondestructive arthritis to a severe, debilitating, erosive joint disease (Lloyd et al., 2012).

Psoriatic arthritis affects fewer people in the United States than rheumatoid arthritis. It has a highly variable presentation, which generally involves pain and inflammation in joints and progressive joint involvement and damage. There are multiple clinical subsets of psoriatic arthritis, including:

- Monoarthritis of the large joints

- Distal interphalangeal arthritis

- Spondyloarthritis, or a symmetrical deforming polyarthropathy similar to that of rheumatoid arthritis (Lloyd et al., 2012)

Left untreated, a proportion of patients may develop persistent inflammation with deforming progressive joint damage which leads to severe physical limitation and disability (Lloyd et al., 2012).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs help with symptomatic relief, but they do not alter the disease course or prevent disease progression. Intra-articular steroid injections can be used for symptomatic relief. Physical or occupational therapy may also be helpful in symptomatic relief (Lloyd et al., 2012).

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs are the mainstay of treatment for patients suffering from psoriatic arthritis. Currently, the most effective class of therapeutic agents for treating psoriatic arthritis is the TNF-α inhibitors; however, these drugs show a 30% to 40% primary failure rate in both randomized clinical trials and registry-based longitudinal studies (Lloyd et al., 2012).

Back Next