Medicine and drug use is highly regulated by the federal government and states to protect people from harm. Regulations require pharmaceutical companies to place warnings on packaging of over-the-counter and prescribed medicines. Federal and state regulations control who is able to prescribe medicines with a high risk for abuse. Medical training institutions teach students to prescribe controlled substances and over the counter medicines safely. Schools of pharmacy teach pharmacists to dispense medicines safely. Pharmaceutical boards regulate the practice of dispensing medicines (OHA, 2014).

Many states require prescriber education on pain and the use of pharmaceutical medicines to control pain. States regulate the age at which individuals can legally purchase and consume alcohol. Federal and state laws establish penalties to control and punish infractions of laws and regulations by individuals (patients, prescribers, and pharmacists), institutions, corporations, and criminal organizations that promote and control drug trade. Yet all of these laws and regulations have not prevented misuse, abuse, addiction, and overdoses due to the use of prescribed medicines, alcohol, and illegal drugs (OHA, 2014).

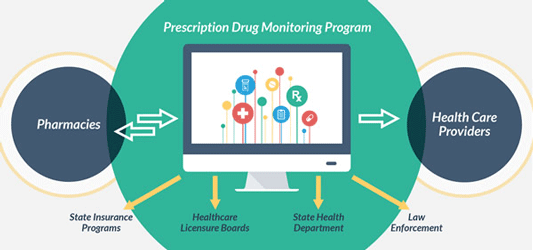

The increase in non-medical use of pharmaceuticals suggests that prevention measures—such as provider and patient education and restrictions on the use of specific formulations—have not been adequate to curb widespread abuse and misuse. Given the societal burden of the problem, additional interventions are needed, such as more systematic provider education, universal use of state prescription drug monitoring programs by providers, routine monitoring of insurance claims information for signs of inappropriate use, and efforts by providers and insurers to intervene when patients use drugs inappropriately (MMWR, 2010).

Preventing Diversion

Diversion is the use of drugs for other than medically necessary or legal purposes or for non-medical or not–medically authorized purposes. Diversion involves, but is not limited to, physicians who sell prescriptions to drug dealers or abusers; pharmacists who falsify records and subsequently sell the drugs; employees who steal from inventory and falsify orders to cover illicit sales; prescription forgers; and individuals who commit armed robbery of pharmacies and drug distributors (DEA, n.d.).

Source: CDC.

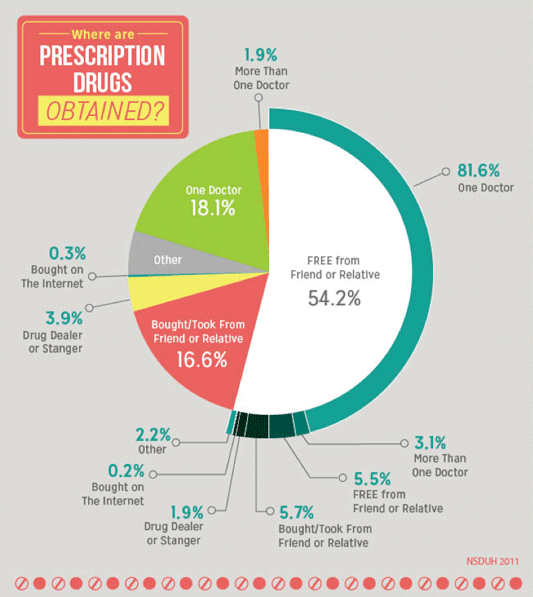

Surveys reveal that diversion of prescription drugs is endemic in communities. Diversion takes place in many contexts, most often when friends and relatives share their prescription pain relievers. Fifty-four percent of those surveyed in the United States reported the source of the pain relievers that they used non-medically was free from their family and friends (OHA, 2014).

Almost all prescription drugs involved in overdoses originate from prescriptions; very few come from pharmacy theft. However, once they are prescribed and dispensed, prescription drugs are frequently diverted to people using them without prescriptions. More than 3 out of 4 people who misuse prescription painkillers use drugs prescribed to someone else. Most prescription painkillers are prescribed by primary care and internal medicine doctors and dentists, not specialists. About 20% of prescribers prescribe 80% of all prescription painkillers (CDC, 2013a).

More than half of prescription drugs are obtained from a friend or relative. Source: NIDA, 2014.

A large number of new unregulated substances (designer drugs) are being abused for their psychoactive properties, often resulting in violent and unpredictable behavior. This growing phenomenon is particularly challenging, first because of the speed with which rogue chemists can modify existing drugs and market them and second because of the ease with which the Internet allows for the sharing of information about and purchase of products such as “spice” and “bath salts” (Volkow, 2013).

Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs

Source: cdc.gov.

AMA Recommendations

The American Medical Association acknowledges that opioid addiction is a national problem that has reached epidemic proportions. They urge physicians to take the following steps to address opioid abuse (AMA, 2016b):

- Register and use your state prescription drug monitoring program to check your patient’s prescription history.

- Educate yourself on managing pain and promoting safe, responsible opioid prescribing.

- Support overdose prevention measures, such as increased access to naloxone.

- Reduce the stigma of substance use disorder and enhance access to treatment.

- Ensure patients in pain aren’t stigmatized and can receive comprehensive treatment.

All on the Same Team: Managing Chronic Pain (9:03)

Patients on opioids and providers work to improve their quality of life. Oregon Pain Guidance

(2016)

https://www.youtube.com/watchv=2kP10Z228Os&feature=youtu.be

Providing Naloxone (Narcan) to Laypeople

Since 1996 an increasing number of programs provide laypeople with training and kits containing the opioid antagonist naloxone hydrochloride (Narcan) to reverse the potentially fatal respiratory depression caused by heroin and other opioids. In 2014 the Harm Reduction Coalition (HRC), a national advocacy and capacity-building organization, surveyed managers of organizations in the U.S. known to provide naloxone kits to laypeople. Managers reported on the amount of naloxone distributed, overdose reversals by bystanders, and other program data for 644 sites that were providing naloxone kits to laypersons as of June 2014. From 1996 through June 2014, surveyed organizations provided naloxone kits to 152,283 laypeople and received reports of 26,463 overdose reversals (Wheeler et al., 2015).

Providing naloxone kits to laypeople reduces overdose deaths, is safe, and is cost-effective. U.S. and international health organizations recommend providing naloxone kits to laypeople who might witness an opioid overdose; to patients in substance use treatment programs; to persons leaving prison and jail; and as a component of responsible opioid prescribing (Wheeler et al., 2015).

Although the number of organizations providing naloxone kits to laypeople is increasing, in 2013 twenty states had no such organization, and nine had less than one layperson per 100,000 population who had received a naloxone kit. Among these 29 states with minimal or no access to naloxone kits for laypeople, 11 had age-adjusted 2013 drug overdose death rates higher than the national median (Wheeler et al., 2015).

At their annual meeting in June 2016, the AMA adopted new policies that encourage physicians to co-prescribe naloxone to patients at risk of an overdose; promote timely and appropriate access to non-opioid and non-pharmacologic treatments for pain; and support efforts to delink payments to healthcare facilities with patient satisfaction scores relating to the evaluation and management of pain (AMA, 2016a).

The new naloxone policies are intended to increase access to the overdose-reversing drug for friends and family members of patients at risk of overdose. The policy also encourages private and public payers to include all forms of naloxone on their preferred drug lists and formularies with nominal or no cost sharing. The policy supports liability protections for physicians and other authorized health care professionals to prescribe, dispense and administer naloxone. Delegates called for policies to enable law enforcement agencies to carry and administer naloxone, as many states have done (AMA, 2016a).

Probuphine: Fighting Opioid Dependence

Medications like buprenorphine and methadone have revolutionized the treatment of people with opioid use disorder. By controlling cravings and withdrawal symptoms without producing a high, these medications enable the patient to engage in treatment and make healthier choices while balance is gradually restored in brain circuits involved in reward and self-control. In people with severe disorders, these circuits are greatly disrupted (NIDA, 2016c).

One of the challenges with all addiction medications, however, is making sure patients adhere to their prescribed regimen. For the medication to be effective, the patient must take their prescription or show up at the clinic daily. This can be challenging for anyone managing life’s responsibilities, especially in times of stress. Failing at this challenge may mean relapse, which can delay recovery (NIDA, 2016c).

In May of 2016 the FDA approved a long-acting buprenorphine implant called Probuphine. This subdermal implant delivers a constant low dose of buprenorphine over six months, the first such tool in the treatment of opioid use disorder. The implant is approved for individuals with opioid dependence who have already been treated with, and are medically stable on, existing orally absorbed buprenorphine formulations. It is a valuable new therapeutic tool for this subset of patients (NIDA, 2016c).

Buprenorphine, which in numerous studies has been shown to significantly improve outcomes for patients, has previously only been available in products that must be taken daily. The Probuphine implant, created by marrying buprenorphine to a polymer, delivers the drug steadily in the body at a low dose, eliminating the need for daily dosing (NIDA, 2016c).

Back Next