Here I lie in my hospital bed

Tell me, sister morphine, when are you coming round again?

Oh, I don’t think I can wait that long

Oh, you see that my pain is so strong

The scream of the ambulance is soundin’ in my ear

Tell me, sister morphine, how long have I been lying here?

What am I doing in this place?

Why does the doctor have no face?

Marianne Faithfull, Sister Morphine

The United States is in the midst of an unprecedented drug overdose epidemic. Since 1999 prescription drug overdose death rates have quadrupled (CDC, 2016b). In 2009, for the first time in U.S. history, drug overdose deaths outnumbered motor vehicle deaths (CDC, 2013a). Since pain was coined “the fifth vital sign” in the 1990s, sales of prescription opioids in the Unites States have quadrupled (see below) (Bartels et al., 2016).

Source: CDC, 2016a.

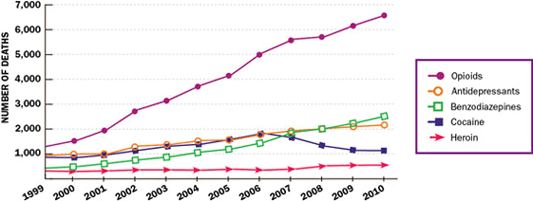

This increase in the prescription of opioids for pain management has been accompanied by a dramatic rise in prescription opioid-associated morbidity and mortality. In 2010 more than 16,000 deaths were attributed to prescription opioids, making them a leading cause of injury death in the general population (Bartels et al., 2016). There are now more deaths from opioid-related overdoses than from all other illicit drugs combined. Emergency department visits, substance treatment admissions, and economic costs associated with opioid abuse have all soared (CDC, 2013a).

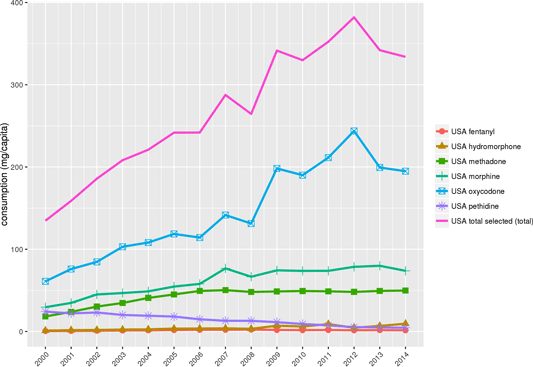

Some startling statistics illustrate the magnitude of the abuse problem. Between 1997 and 2011 the U.S. population increased only 16%, however the number of prescription pain medications sold by pharmacies increased significantly more than that. Between 1997 and 2011:

- Oxycodone sales increased by 1,259%

- Hydrocodone sales increased by 356%

- Methadone sales increased by 1,099%

- Fentanyl sales increased by 711%

- Morphine sales increased by 246%

- Buprenorphine sales increased from 17 grams in 2002 to 1,639 kg in 2011 (McDonald & Carlson, 2013)

USA Opioid Consumption (mg/capita), 2000—2014

Sources: International Narcotics Control Board; World Health Organization population data By: Pain and Policy Studies Group, University of Wisconsin/WHO Collaborating Center, 2016.

The increased availability of opioid analgesics means they are being used in ways that are unsafe or unintended. OxyContin, for example, which was designed as a slow-release, oral medication is now being crushed, then snorted or injected, with lethal consequences. To combat this, new formulations are being designed to deter some of these abuses. For example, a new formulation of OxyContin releases from 21% to 48% less opioid when tampered with (milled, manually crushed, dissolved, and boiled) than the original version (Raffa et al., 2012).

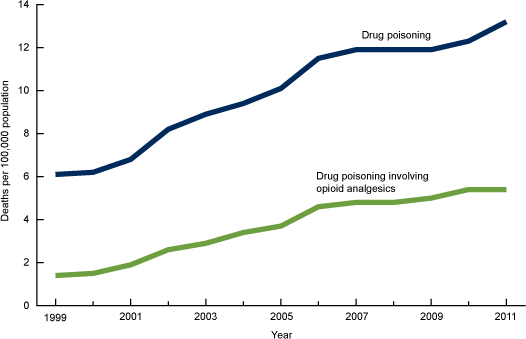

Benzodiazepines have been reported frequently in deaths involving opioid analgesics. Over the past decade, there has been an upward trend in the presence of benzodiazepines in opioid-analgesic poisoning deaths. In 1999 benzodiazepines were involved in 13% of the opioid analgesic poisoning deaths; by 2011, 31% of the opioid analgesic–related drug-poisoning deaths also involved benzodiazepines (NCHS, 2014).

Age-Adjusted Drug-Poisoning and Opioid-Analgesic Poisoning Death Rates, United States, 1999–2011

Source: NCHS, 2014.

Prescription Drug Abuse

Prescription drug abuse is the use of a medication without a prescription, in a way other than as prescribed, or for the experience or feelings elicited. According to several national surveys, prescription medications, such as those used to treat pain, attention deficit disorders, and anxiety, are being abused at a rate second only to marijuana among illicit drug users. The consequences of this abuse have been steadily worsening, reflected in increased treatment admissions, emergency room visits, and overdose deaths (NIDA, 2014b).

Prescription drug abuse can include taking a drug prescribed for someone else, taking more of the medication than was prescribed, taking medication more frequently than was directed, or altering the formulation (crushing, snorting) so as to obtain a greater amount of active agent than was originally intended (NIDA, 2012).

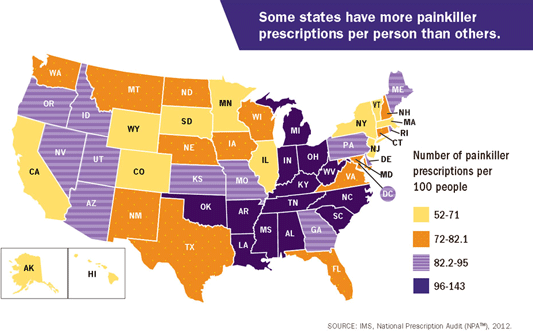

Prescribing rates for opioids vary widely across states. In 2012 healthcare providers in the highest-prescribing state wrote almost 3 times as many opioid painkiller prescriptions per person as those in the lowest prescribing state. Some of the increased demand for prescription opioids is from people who use them non-medically, who sell them, or who obtain them from multiple prescribers. Many states report problems with for-profit, high-volume pain clinics (so-called pill mills) that prescribe large quantities of painkillers to people who don’t need them medically (CDC, 2016a).

Source: CDC, 2016a.

Opioid pain medication abuse presents serious risks: from 1999 to 2014, more than 165,000 persons died from overdose related to opioid pain medication in the United States (CDC, 2016b). In the past decade, while the death rates for the top leading causes of death such as heart disease and cancer have decreased substantially, the death rate associated with opioid pain medication has increased markedly. Sales of opioid pain medication have increased in parallel with opioid-related overdose deaths. The Drug Abuse Warning Network estimated that >420,000 ED visits were related to the misuse or abuse of narcotic pain relievers in 2011, the most recent year for which data are available (CDC, 2016b).

Having a history of a prescription for an opioid pain medication increases the risk for overdose and opioid use disorder, highlighting the value of guidance on safer prescribing practices for clinicians. A recent study of patients aged 15 to 64 years receiving opioids for chronic noncancer pain and followed for up to 13 years revealed that:

- 1 in 550 patients died from opioid-related overdose at a median of 2.6 years from their first opioid prescription, and

- 1 in 32 patients who escalated to opioid dosages >200 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) died from opioid-related overdose. (CDC, 2016b)

Did You Know. . .

Enough prescription painkillers were prescribed in 2010 to medicate every American adult around-the-clock for one month (CDC, n.d.).

Several factors have contributed to the rise in opioid prescriptions for chronic noncancer. These include reservations against alternative pain therapies, especially those related to adverse events associated with long-term use of NSAIDs, aggressive and, at times, misleading product marketing by the manufacturers, and the widespread belief that opioid therapy carries a low risk of addiction potential (Xu & Johnson, 2013).

Methadone

Methadone is a synthetic narcotic first developed by German scientists during World War II to address a shortage of morphine. Methadone was introduced into the United States in 1947 as an analgesic (Dolophinel) and has emerged as a commonly prescribed medication for the management of pain. Methadone is also used for the treatment of opioid dependence, in which case it may be dispensed only in federally approved Opioid Treatment Programs.

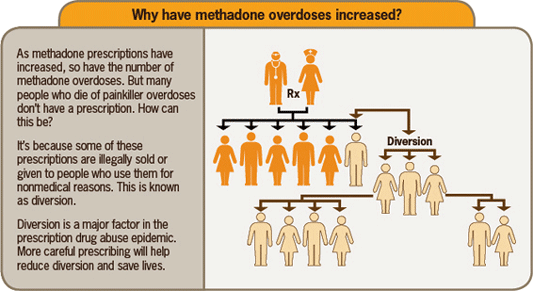

Methadone has been associated with disproportionate numbers of overdose deaths relative to the frequency with which it is prescribed for pain. Methadone has been found to account for as much as one-third of opioid-related overdose deaths involving single or multiple drugs in states that participated in the Drug Abuse Warning Network, which was more than any opioid other than oxycodone, despite representing <2% of opioid prescriptions outside of opioid treatment programs in the United States; further, methadone was involved in twice as many single-drug deaths as any other prescription opioid (MMWR, 2016).

Source: CDC, 2012.

Methadone differs from most other opioids because of its long half-life, delayed onset, narrow therapeutic window, and interactions with drugs such as alcohol and benzodiazepines. Methadone is less expensive than other opioids and is increasingly being prescribed as a cost-effective alternative, partly due to pressure from insurance companies.

Fentanyl

Drug incidents and overdoses related to fentanyl are occurring at an alarming rate throughout the United States and represent a significant threat to public health and safety. Often laced in heroin, fentanyl and fentanyl analogues produced in illicit clandestine labs are up to 100 times more powerful than morphine and 30 to 50 times more powerful than heroin.

DEA Administrator Michele M. Leonhart, 2015

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid analgesic that is similar to morphine but is 50 to 100 times more potent. It is a schedule II prescription drug, and it is typically used to treat patients with severe pain or to manage pain after surgery. It is also sometimes used to treat patients with chronic pain who are physically tolerant to other opioids.

Fentanyl can be absorbed through the skin (fentanyl patch), by IV injection, by mouth (for breakthrough cancer pain), and intranasally. There are two types of fentanyl:

- Pharmaceutical fentanyl, which is primarily prescribed to manage acute and chronic pain associated with advanced cancer.

- Non-pharmaceutical fentanyl, which is illegally made, and is often mixed with heroin and/or cocaine—with or without the user’s knowledge—in order to increase the drug’s effect.

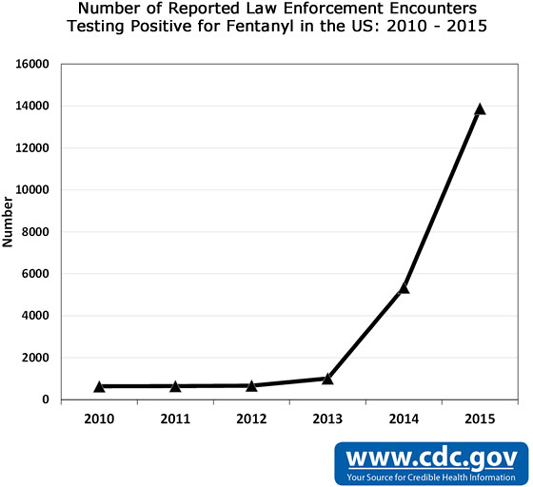

There has been a sharp increase in the number of fentanyl overdoses in recent years. Most of the increases in fentanyl deaths over the last three years do not involve prescription fentanyl but are related to illicitly made fentanyl that is being mixed with or sold as heroin—with or without the users’ knowledge—and increasingly as counterfeit pills. In July 2016 the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) issued a nationwide report indicating hundreds of thousands of counterfeit prescription pills have been entering the U.S. drug market since 2014, some containing deadly amounts of fentanyl and fentanyl analogs. The current fentanyl crisis continues to expand in size and scope across the United States (CDC, 2016a).

This graph uses data from the DEA National Forensic Laboratory Information System (NFLIS) on the number of law enforcement drug submissions that test positive for fentanyl from 2014 to 2015 as of July 1, 2016. Source: CDC.

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is used in medication-assisted treatment (MAT) to help people reduce or quit their use of heroin or other opiates, such as pain relievers like morphine (SAMHSA, 2016). Buprenorphine and Suboxone (a combination of buprenorphine and naloxone) are used to treat opioid dependence. These medications work to prevent withdrawal symptoms when someone stops taking opioid drugs by producing similar effects to these drugs. In recent years, buprenorphine has surpassed methadone as a drug of diversion and abuse (Medline Plus, 2016).

Buprenorphine is the first medication to treat opioid dependency that is permitted to be prescribed or dispensed in physician offices, significantly increasing treatment access. Because of buprenorphine’s opioid effects, it can be misused, particularly by people who do not have an opioid dependency. Naloxone is added to buprenorphine to decrease the likelihood of diversion and misuse of the combination drug product. When these products are taken as sublingual tablets, buprenorphine’s opioid effects dominate and naloxone blocks opioid withdrawals. If the sublingual tablets are crushed and injected, however, the naloxone effect dominates and can bring on opioid withdrawals (SAMHSA, 2016).

Analysis of law enforcement samples by the National Forensic Laboratory Information System indicated that, in contrast to methadone, the number of buprenorphine reports increased from 90 in 2003 (one year after buprenorphine was approved to treat opioid dependence) to more than 10,000 in 2010, but has increased more slowly since then, reaching a high of nearly 12,000 in 2013. The majority of buprenorphine reports were from the Northeast U.S. census region, while the West had the lowest number (CESAR, 2014).

Drug-Related Deaths in Oregon

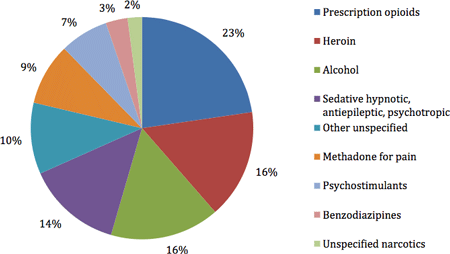

In 2012 Oregon had the highest rate of non-medical use of prescription pain relievers in the nation. That year, a total of 346 individuals died due to drug overdose (OHA, 2014).

Prescription opioids accounted for about a quarter of unintentional and undetermined overdose deaths in Oregon in 2012. Methadone (prescribed for pain) accounted for 40% of the 164 prescription opioid deaths in 2012. Although methadone overdose death rates peaked in 2006 and have declined since 2006–2008, the rates in 2012 are nearly double the rates in 2000. More than 16,000 individuals had at least one prescription for methadone in 2012 (OHA, 2014).

Percent of Unintentional and Undetermined Overdose Deaths Due to Prescribed Medications, Illicit Drug, and Alcohol Oregon, 2012

Source: Oregon Health Authority, 2014.

Although drug poisoning deaths associated with illicit drugs such as heroin and cocaine have increased in recent years, prescription opioid analgesics are increasingly a factor in drug poisoning deaths. In Oregon, between 2000 and 2012:

- 4,182 people died in Oregon due to unintentional and undetermined drug overdose (322 per year).

- Unintentional and undetermined drug overdose death rates appear to have peaked in 2007 at 11.4 per 100,000 and declined to 8.9 per 100,000 in 2012. Nonetheless, the overdose death rate in 2012 remains 1.9 times higher than in 2000.

- The highest rates of death due to unintentional and undetermined drug overdose occurred among Caucasian and non-Latino Oregonians for every type of drug. (OHA, 2014)

In Oregon, more males than females have died from unintentional prescription drug overdose with a ratio of 1.5 males to 1 female. Unintentional overdose death rates significantly increase for males and females starting at age 25. The peak ages for deaths are ages 45-54 (OHA, 2014).

Success in Oregon

As a Core Violence and Injury Prevention Program funded grantee, the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) reports the rate of poisoning due to prescription opioid overdose in Oregon declined 38% between 2006 and 2013. Oregon’s rate of death associated with methadone poisoning decreased 58% in the same time period.

Key initiatives to address the problem include the:

- establishment of a PDMP to track prescriptions of controlled substances;

- implementation of prior authorization for Methadone doses >100mg/day under Medicaid;

- education and access of lay persons to provide naloxone to persons suspected of overdose; and

- physician and allied health care trainings about safe and effective pain care.

OHA continues to promote adoption of their PDMP, and works with health systems, insurers and other partners to increase access to medication assisted treatment and non-pharmaceutical pain care for chronic non-cancer pain.

Source: CDC, 2016a.

Intertwined Epidemics: Prescription Opioids and Heroin

The enormous increase in the availability of prescription pain medications is drawing new users to these drugs and changing the geography and age-grouping of opiate-related overdoses. While many drugs and medicines have potential for overdose, the use of both prescription opioids and heroin (often taken in combination with other medicines and drugs) has increased since 1999. With increased use of opioids, communities have seen increases in overdose hospitalizations and deaths and need for treatment (OHA, 2014).

Most of the current cases of opioid-related overdoses can be traced to two fronts: (1) illegal heroin consumption, and (2) the illicit use or misuse of prescription opioids. The rise in prescription opioid-related overdose deaths has been particularly alarming in rural areas; between 1999 and 2004 prescription opioid-related overdose deaths increased 52% in large urban counties and a staggering 371% in non-urban counties (Unick et al., 2013).

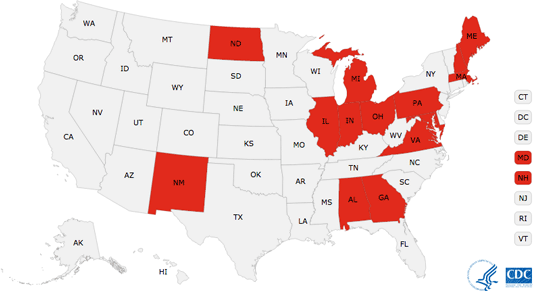

Significant increases in drug overdose death rates were seen in the Northeast, Midwest and South census regions. In 2014 the five states with the highest rates of death due to drug overdose were West Virginia, New Mexico, New Hampshire, Kentucky, and Ohio. Fourteen other states reported statistically significant increases in the rate from 2013 to 2014: Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Virginia (CDC, 2016b).

Drug Overdose Increase, 2013–2014

Statistically significant drug overdose death rate increase from 2013 to 2014, U.S. states.

There is an evolving flux between prescription opioid use and heroin use in urban areas. Ethnographic work from Montreal shows that individuals at risk for heroin use have begun shifting to injecting prescription opioids. Additional evidence from Baltimore and Washington State suggests a high prevalence of prescription abuse in injection drug using populations, often preceding heroin use. Interestingly, recent changes to the formulation of OxyContin, the brand name long-acting form of oxycodone, have been linked to a self-reported rise in heroin use. What these studies suggest is that prescription opioid misuse and heroin use are intertwined (Unick et al., 2013).

Opioid Abuse Among Adolescents and Young Adults

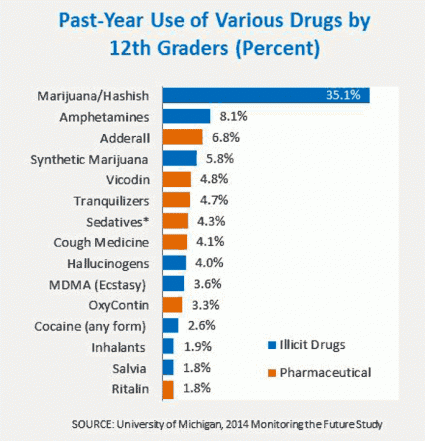

Adolescents and young adults are especially vulnerable to prescription drug abuse, particularly opioids and stimulants. According to the Monitoring the Future (MTF) survey, an ongoing study of the behavior and attitudes of American youth involving nearly 45,000 8th, 10th, and 12th grade students, although there has been a decline in the use of certain illicit drugs, psychotherapeutic drugs now make up a significantly larger part of the overall U.S. drug problem than was true 10 to 15 years ago. This is in part because use increased for many prescription drugs over that period, and in part because use of a number of street drugs has declined substantially since the mid to late 1990s (Johnston et al., 2015).

It seems likely that young people are less concerned about the dangers of using these prescription drugs because they are widely used for legitimate purposes. Also, prescription psychotherapeutic drugs are now being advertised directly to the consumer, which implies that they are safe to use. Fortunately, the use of most of these drugs has either leveled or begun to decline in the past few years. The proportion of 12th graders misusing any of these prescription drugs (eg, amphetamines, sedatives, tranquilizers, or narcotics other than heroin) in the prior year continued to decline in 2015 down from its high in 2005 (Johnston et al., 2015).

Amphetamine use without a doctor’s orders—currently the second most widely used class of illicit drugs after marijuana—continued a gradual decline in 2015 in all grades, though the one-year declines did not reach statistical significance. Use of narcotics other than heroin without a doctor’s orders (measured only in 12th grade) also continued a gradual decline begun after 2009 (Johnston et al., 2015).

Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2015.

Opioid Abuse Among Middle-Aged and Older Adults

Prescription opioid–related overdoses rates are increasing the most in middle-aged individuals. Older adults represent another area of concern. Although older adults currently comprise just 13% of the population, they account for more than one-third of total outpatient spending on prescription medications in the United States. Older patients are more likely to be prescribed long-term and multiple prescriptions, which could lead to misuse or abuse (NIDA, 2014b).

The high rates of comorbid illnesses in older populations, age-related changes in drug metabolism, and the potential for drug interactions may make any of these practices more dangerous than in younger populations. Further, a large percentage of older adults also use over-the-counter medicines and dietary supplements, which (in addition to alcohol) could compound any adverse health consequences resulting from prescription drug abuse (NIDA, 2014b).

Gender Differences in Opioid Abuse

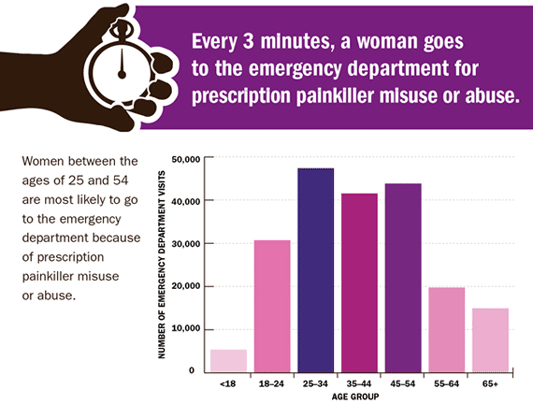

Overall, adult men and women have roughly similar rates of nonmedical use of prescription drugs, although some studies suggest that women are more likely than men to be prescribed drugs, particularly narcotics and anti-anxiety drugs. Adolescent females are more likely than males to use psychotherapeutic drugs nonmedically. Research has also suggested that women are at increased risk for nonmedical use of narcotic analgesics and tranquilizers such as benzodiazepines (CDC, 2013b).

Prescription pain medication overdoses are increasing among women. Although men are still more likely to die of prescription painkiller overdoses (more than 10,000 deaths in 2010), the gap between men and women is closing. Deaths from prescription painkiller overdose among women have risen more sharply than among men; since 1999 the percentage increase in deaths was more than 400% among women compared to 265% in men. This rise relates closely to increased prescribing of these drugs during the past decade (CDC, 2013b).

Deaths of Women from Prescription Painkillers, 1999–2010

Prescription painkiller deaths among women have increased dramatically since 1999. Source: CDC, 2013b.

Prescription Painkillers: Growing Problem Among Women

- More than 5 times as many women died from prescription painkiller overdoses in 2010 than in 1999.

- Women between the ages of 25 and 54 are more likely than other age groups to go to the emergency department from prescription painkiller misuse or abuse.

- Women ages 45 to 54 have the highest risk of dying from a prescription painkiller overdose.*

- Non-Hispanic white and American Indian or Alaska Native women have the highest risk of dying from a prescription painkiller overdose.

- Prescription painkillers are involved in 1 in 10 suicides among women.

*Death data include unintentional, suicide, and other deaths. Emergency department visits only include suicide attempts if an illicit drug was involved in the attempt.

Prescription Painkillers Affect Women Differently than Men

- Women are more likely to have chronic pain, be prescribed prescription painkillers, be given higher doses, and use them for longer time periods than men.

- Women may become dependent on prescription painkillers more quickly than men.

- Women may be more likely than men to engage in “doctor shopping” (obtaining prescriptions from multiple prescribers).

- Abuse of prescription painkillers by pregnant women can put an infant at risk.

Source: CDC, 2013b.

Source: CDC.

Opioid Abuse in Patients with Chronic Pain

Diagnosed chronic pain patients make up less than 1% of the insured population in the United States but consume about 45% of all prescription opioids. It has been estimated that up to 40% of pain patients on chronic opioid therapy display aberrant drug-related behaviors (Raffa et al., 2012).

Chronic pain has been intertwined with substance abuse: 33% of individuals in a substance abuse program reported suffering from chronic pain and individuals in substance abuse treatment programs with chronic pain were significantly more likely to abuse opioids than those not reporting chronic pain. The term rational abuse has been put forth to describe chronic pain patients who abuse opioids because of undertreated pain, but very little is known about this population (Raffa et al., 2012).

Back Next