Informal caregivers provide regular care or assistance to a friend or family member who has a health problem or disability.

CDC, 2019c

The CDC considers the health of caregivers to be an important and growing public health priority that affects the quality of life for millions of individuals (CDC, 2018d).

Informal or unpaid caregivers (family members or friends) are the backbone of long-term care provided in people’s homes. While some aspects of caregiving may be rewarding, caregivers can also be at increased risk for negative health consequences, which may include stress, depression, difficulty maintaining a healthy lifestyle, and shortchanging their own preventive health services.

As the number of older Americans increases, so will the number of caregivers needed to provide care. The number of people 65 years old and older is expected to double between 2000 and 2030. It is expected that there will be 71 million people aged 65 years old and older when all baby boomers are at least 65 years old in 2030.

Currently, there are 7 potential family caregivers per adult. By 2030, there will be only 4 potential family caregivers per adult (CDC, 2018d).

Role of Caregivers

Caregivers provide assistance with another person’s social or health needs. Caregiving may include help with one or more activities important for daily living such as bathing and dressing, paying bills, shopping and providing transportation. It also may involve emotional support and help with managing a chronic disease or disability. Caregiving responsibilities can increase and change as the recipient’s needs increase, which may result in additional strain on the caregiver (CDC, 2019c).

Caregivers can be unpaid family members or friends or paid caregivers. Informal or unpaid caregivers are the backbone of long-term care provided in people’s homes. In particular, middle-aged and older adults provide a substantial portion of this care in the United States, as they care for children, parents, or spouses. These informal caregivers are the focus here (CDC, 2019c).

Caregiving can affect the caregiver’s life in a myriad of ways including his/her ability to work, engage in social interactions and relationships, and maintain good physical and mental health. Caregiving also can bring great satisfaction and strengthen relationships, thus enhancing the caregivers’ quality of life. As the population ages and disability worsens, it is critical to understand the physical and mental health burden on caregivers, the range of tasks caregivers may preform, and the societal and economic impacts of long-term chronic diseases or disability. Gathering information on these topics enables us to plan for public health approaches to assist individuals as well as their communities and maintain the health of caregivers and care recipients. (CDC, 2019c).

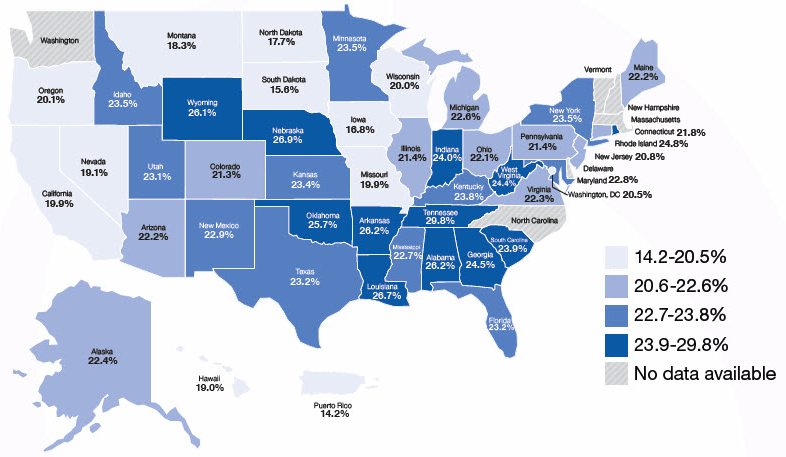

Adults Aged 45 Years or Older Who Reported Being a Caregiver to a Friend or Family Member

Source: CDC, 2019c.

Who Are Caregivers?

Caregivers provide care to people who need some degree of ongoing assistance with everyday tasks on a regular or daily basis. The recipients of care can live either in residential or institutional settings, range from children to older adults, and have chronic illnesses or disabling conditions (CDC, 2018d).

Approximately 25% of U.S. adults 18 years of age and older reported providing care or assistance to a person with a long-term illness or disability in the past 30 days, according to 2009 data from CDC’s state-based Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. This is termed “informal or unpaid care” because it is provided by family or friends rather than by paid caregivers. The one-year value of this unpaid caregiver activity was estimated as $450 million dollars in 2009 (CDC, 2018d).

Effects on Caregivers

Informal or unpaid caregiving has been associated with:

- Elevated levels of depression and anxiety

- Higher use of psychoactive medications

- Worse self-reported physical health

- Compromised immune function

- Increased risk of early death

Over half (53%) of caregivers indicate that a decline in their health compromises their ability to provide care. Furthermore, caregivers and their families often experience economic hardships through lost wages and additional medical expenses. In 2009 more than 1 in 4 (27%) of caregivers of adults reported a moderate to high degree of financial hardship as a result of caregiving.

There are positive aspects of caregiving, and many people note that providing care for a family member with a chronic illness or a disabling condition offers:

- A sense of fulfillment

- Establishment of extended social networks or friendship groups associated with caregiving

- Feeling needed and useful

- Learning something about oneself, others, and the meaning of life (CDC, 2018d)

There are a number of things caregivers can do to reduce stress and make their job easier. One is to make sure they have detailed organized information about the person they are caring for.

Care Planning

Developing and maintaining a care plan helps balance the caregiver’s life and that of the person to whom they are providing care. Not every care situation requires the same amount of work and the more there is to attend to the more being organized will help.

A caregiver for someone with Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, or another chronic health condition may manage everything from medications and getting dressed in the morning to doctor appointments, social events, and meals (CDC, 2017j). (See the earlier section of this course on dementia for additional caregiver information.)

A care plan is a form that summarizes a person’s health conditions and current treatments for their care (one is available on the CDC Caregiver website). The plan should include information about:

- Health conditions

- Medications

- Healthcare providers

- Emergency contacts

- Caregiver resources

Talking with the person’s doctor may be helpful in completing the care plan. At that time, you can also discuss advance care plan options, such as what follow-up care is necessary, end-of-life care options, and resources that are available to help make things easier for you as a caregiver. Try to update the care plan every year or if there is a change in the person’s health or medications, and remember to respect the care recipient’s privacy after reviewing their personal information (CDC, 2017j).

Developing a care plan

- Start a conversation about care planning with the person you take care of. If your care recipient isn’t able to provide input, anyone who has significant interaction with the care recipient (a family member or home nurse aide) can help complete the form.

- Talk to the doctor of the person you care for or another healthcare provider. A physician can review the form you started and help to complete it, especially if there is a conversation about advance care planning.

- Ask about relevant care options are relevant. Medicare covers appointments that are scheduled to manage chronic conditions and for discussing advance care plans. Beginning in January of 2017, Medicare covers care planning appointments specifically for people with Alzheimer’s, other dementias, memory problems, or suspected cognitive impairment.

- Discuss any needs you have as a caregiver; 84% of caregivers report they could use help on caregiving topics especially related to safety at home, dealing with stress, and managing their care recipient’s challenging behaviors. Caregivers of people with dementia or Alzheimer’s are particularly at greater risk for anxiety, depression, and lower quality of life compared to caregivers of people with other chronic conditions (CDC, 2017j).

Benefits of a care plan

- Care plans can reduce ED visits, hospitalizations, and improve overall medical management for people with a chronic health condition, like Alzheimer’s disease, resulting in better quality of life for all care recipients.

- Care plans can provide supportive resources for you, the caregiver, to continue leading a healthy life of your own (CDC, 2017j).

Keep a care plan to reduce stress and allow quick action in emergencies such as the CDC Caregiving Care Plan Form available at their website (CDC, 2018e).

Resources for Caregivers

The National Family Caregiver Support Program (NFCSP) provides grants to states and territories to fund various supports that help family and informal caregivers care for older adults in their homes for as long as possible. It was established in 2000 and authorized under the Older Americans Act of 1965 Act (see earlier section of course) (ACL, 2019b).

The grantees provide the following kinds of services:

- Information to caregivers about available services

- Assistance to caregivers in gaining access to the services

- Individual counseling, organization of support groups, and caregiver training

- Respite care; and

- Supplemental services, on a limited basis

The services are coordinated with other state and community-based services. Research has demonstrated positives benefits for caregivers in reducing depression, anxiety, and stress, and enabling them to provide care longer (ACL, 2019b).

The 2016 Reauthorization of the Older Americans Act authorized four specific populations of caregivers as eligible to receive services:

- Adult family members or other informal caregivers age 18 and older providing care to individuals 60 years of age and older

- Adult family members or other informal caregivers age 18 and older providing care to individuals of any age with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders

- Older relatives (not parents) age 55 and older providing care to children under the age of 18; and

- Older relatives, including parents, age 55 and older providing care to adults ages 18 to 59 with disabilities (ACL, 2019b)

American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) Caregiving

The prevalence of caregivers in the AI/AN population is greater than that of the general U.S. population. Like people of all racial/ethnic groups, AI/AN families want to care for their elders and the elders want to remain in their homes and have family care as long as possible. One concern for AI/AN communities is that there is an out-migration from the reservations to urban areas for jobs, leaving a potentially smaller pool of prospective caregivers (CDC, 2018f).

For the American Indian/Alaskan Native (AI/AN) population, taking care of an elder is a continuation of an ancient custom of extended family and lifelong care for family. Indian family caregivers are similar to non-Indian caregivers in many ways; however, the resources available to them are much more limited. In addition, eligibility criteria for long-term care services are often couched in language that is not culturally sensitive. Surveys show AI/AN families would like training on how to take care of an older adult, help to coordinate care and navigate the health system, respite care and adult daycare to give the caregiver a break, support groups, and more services for their care recipient (CDC, 2018f).

Caregiver Advise, Record, Enable (CARE) Act

The AARP pioneered this model legislation, which is now law in 44 states, to provide much needed support for family caregivers when the person they care for is transitioning back home from a hospitalization.

The CARE Act requires hospitals to:

- Record the name of the family caregiver on the medical record of the person they care for.

- Inform the family caregivers when that person is to be discharged.

- Provide the family caregiver with education and instruction for the medical tasks he or she will need to perform for the patient at home.

Family caregivers are often called upon to manage multiple medications, provide wound care, manage special diets, give injections, and operate monitors or other specialized medical equipment. Most have no formal training, but being able to do these task helps keep their family member at home and out of an institution. Being able to prepare for the patient’s return home and get training on how to care for them is something many have asked for (AARP, 2016).