Primary prevention refers to the treatment of individuals with no history of stroke. Measures often include use of platelet anti-aggregants, statins, and exercise. The 2011 AHA/ASA guidelines for the primary prevention of stroke emphasize the importance of lifestyle in reducing modifiable risk factors (Goldstein et al., 2011).

Secondary preventive measures are important for people already identified as having had a stroke. For these individuals, lifestyle changes are appropriate; however, there is an increased emphasis on use of medications to manage medical co-morbidities as well as those directed specifically toward stroke.

The 2011 AHA/ASA guidelines recommended emergency department-based smoking cessation interventions and considered it reasonable for the ED to screen all patients for hypertension and substance abuse, especially stimulant abuse (Goldstein et al., 2011).

Guidelines issued in 2014 by the AHA/ASA on the secondary prevention of stroke continue to emphasize nutrition and lifestyle, but include a new section on aortic atherosclerosis (Hughes, 2014). These recommendations include the following:

- Patients who have had a stroke or TIA should be screened for diabetes and obesity.

- Patients should be screened for sleep apnea.

- Patients should undergo a nutritional assessment and be advised to follow a Mediterranean-type diet.

- Patients who have had a stroke of unknown cause should undergo long-term monitoring for atrial fibrillation.

- The new oral anticoagulants dabigatran, apixaban, and rivaroxaban are among the drugs recommended for patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation.

- The guidelines no longer recommend the use of niacin or fibrates to raise high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol or reduce secondary stroke risk. (Hughes, 2014)

Despite the advent of new treatments for acute ischemic stroke and the promise of other acute therapies, prevention remains the best approach for reducing the incidence of stroke. Age, gender, race, family history, and medical history (such as a previous stroke) are non-modifiable risk factors for stroke. But those who practice a healthy lifestyle have an 80% lower risk of a first stroke compared with those who do not (JAHA, 2011b).

Once a stroke occurs, rapid diagnosis is essential so that clot-busting drugs or other treatment can be given immediately, because “time is brain.” However, many gaps have been identified in the public knowledge of stroke symptoms. It has long been the goal of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), in conjunction with the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American Stroke Association (ASA), to increase public awareness of stroke signs and symptoms.

The public needs education about lifestyle changes that can reduce their risk of stroke. Messages about prevention have focused on modifiable risk factors such as reducing high blood pressure, reducing cholesterol, improving emergency response, decreasing tobacco use, improving nutrition, increasing physical activity, decreasing obesity, and decreasing and controlling diabetes.

Blood Pressure

Hypertension remains the most important, well-documented, modifiable risk factor for stroke, and treatment of hypertension is among the most effective strategies for preventing both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.

Journal of the American Heart Association, 2011

About 1 out of 3 American adults has high blood pressure and another 25% have pre-hypertension—blood pressure numbers that are higher than normal, but not yet in the high blood pressure range. In 2010 high blood pressure cost the United States $76.6 billion in healthcare services, medications, and missed days of work. About 70% of those with high blood pressure who took medication had their high blood pressure controlled (CDC, 2014c).

Cholesterol

Approximately 1 in every 6 adults—more than 16% of the U.S. adult population—has high total cholesterol (240 mg/dL and above). People with no additional risk factors, but with high total cholesterol, have approximately twice the risk of heart disease as people with optimal levels (below 200 mg/dL). Lowering saturated fat and increasing fiber in the diet, maintaining a healthy weight, and getting regular physical activity can reduce a person’s risk for cardiovascular disease and stroke by lowering cholesterol levels. In addition to lifestyle changes, statins (eg, lovastatin, simvastatin) may be needed to reduce cholesterol levels (CDC, 2013b).

Emergency Response

Heart attacks and strokes are life-and-death emergencies in which every second counts. Nearly half of all stroke and heart attack deaths occur before patients are transported to hospitals. For this reason, prehospital emergency medical service (EMS) organizations and providers are vital partners with public health to reduce death and disability from heart attacks and strokes. Additionally, it is important for the public to recognize the major warning signs and symptoms and the need to immediately call 911(CDC, 2014d).

Tobacco

Cigarette smokers have twice the risk of stroke compared to nonsmokers. Smoking decreases the amount of oxygen in the blood, causing the heart to work harder. Smoking promotes atherosclerosis and increases levels of blood clotting factors (NINDS, 2015).

Nutrition

A healthy diet can reduce the risk for acquiring medical conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, high lipid levels, coronary artery disease, and obesity. All of these conditions increase the chance of having a stroke. Recent studies indicate that a diet rich in fruits and vegetables can lower the risk of heart disease and stroke. Those people who ate more than five servings of fruits and vegetables per day had roughly a 20% lower risk of coronary heart disease and stroke compared with individuals who ate less than three servings per day (Harvard School of Public Health, 2011a).

Another study found that a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and low-fat dairy products lowered systolic blood pressure by 11mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure by almost 6mm Hg—as much as achieved by medications (Harvard School of Public Health, 2011a).

The average American consumes 3400 mg of sodium each day, most of which comes from processed, store-bought, and restaurant foods. Only about 5% comes from salt added during cooking and about 6% comes from adding salt at the table. Current dietary guidelines recommend that adults should consume no more than 2,300 mg of sodium per day. However, the following population groups should consume no more than 1,500 mg per day:

- People 40 years of age or older

- African Americans

- Those with hypertension (CDC, 2014e)

Two out of three (69%) adults in the United States fall into one or more of these three groups that are at especially high risk for health problems from too much sodium (CDC, 2014e).

Blood pressure rises with increasing amounts of sodium in the diet, and sodium reduction lowers cardiovascular disease and death rates over the long term. Higher salt intake is associated with a 23% increase in stroke and a 14% increase in heart disease (Harvard School of Public Health, 2011b).

Physical Activity

Physical activity can help maintain a healthy weight and lower cholesterol and blood pressure. The Surgeon General recommends that adults should engage in moderate-intensity exercise for at least 30 minutes on most days of the week (CDC, 2014f).

Obesity

Because people who are overweight or obese have an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and stroke, weight management can reduce a person’s risk from these factors (CDC, 2014f).

Diabetes

People who have diabetes are at least twice as likely as someone who does not have diabetes to have heart disease or a stroke. People with diabetes also tend to develop heart disease or have strokes at an earlier age than other people. Women who have not gone through menopause usually have less risk of heart disease than men of the same age. But women of all ages with diabetes have an increased risk of heart disease because diabetes cancels out the protective effects of being a woman in her childbearing years (NDIC, 2014).

People with diabetes who have already had one heart attack run an even greater risk of having a second one. In addition, heart attacks in people with diabetes are more serious and more likely to result in death. High blood-glucose levels over time can lead to atherosclerosis (NDIC, 2014). If blood-glucose levels are high at the time of a stroke, then brain damage is usually more severe and extensive than when blood glucose is well-controlled. Treating diabetes can delay the onset of complications that increase the risk of stroke (NINDS, 2014b).

Carotid Endarterectomy

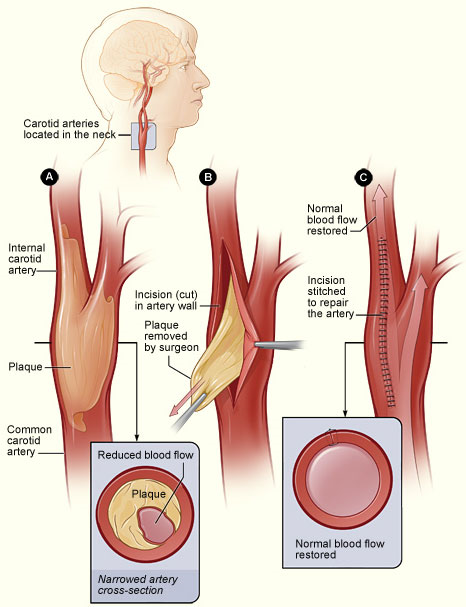

Carotid endarterectomy is a surgical procedure in which fatty deposits are removed from one of the two carotid arteries located in the neck. Carotid endarterectomy is done to prevent stroke for those who have a certain level of blockage and to prevent recurrent stroke; this is not an acute stroke treatment.

The carotid arteries are the main suppliers of blood to the brain. Two recent NINDS trials showed that carotid endarterectomy is a safe and effective stroke prevention therapy for most people with greater than 50% stenosis of the carotid arteries when performed by a qualified and experienced neurosurgeon or vascular surgeon (NINDS, 2015a).

Patients may need a carotid endarterectomy if they have:

- Had a TIA or stroke with at least 70% narrowing of the carotid artery.

- Had a TIA or mild stroke in the past 6 months that did not leave them completely disabled, and the carotid arteries are at least 50% narrowed.

- Not had a TIA or stroke, but the carotid arteries are narrowed 60% or more and they have a low risk of complications from the surgery. (WebMD, 2014)

Those most likely to benefit from surgery are people who have had symptoms and have 70% or greater narrowing (stenosis) of their carotid artery. People with less than 50% narrowing do not seem to benefit from surgery (WebMD, 2014).

Carotid Endarterectomy

Figure A shows a carotid artery with plaque buildup. The inset image shows a cross section of the narrowed carotid artery. Figure B shows how the carotid artery is cut and how the plaque is removed. Figure C shows the artery stitched up and normal blood flow restored. The inset image shows a cross section of the artery with plaque removed and normal blood flow restored. Source: NIH, n.d.

A large clinical trial was done to test the effectiveness of carotid endarterectomy versus carotid stenting. Stenting involves inserting a long, thin catheter into an artery in the leg and threading the catheter through the vascular system into the stenosis of the carotid artery. Once the catheter is in place, the radiologist expands the stent with a balloon on the tip of the catheter to open the stenosis (NINDS, 2015a).

Following up after an average of 2.5 years, there was no difference in the estimated 4-year rates of early stroke and later stroke, heart attack, or death—between carotid artery stenting and carotid endarterectomy. The study also found that the age of the patient made a difference. At age 69 and younger, stenting results were slightly better. Conversely, for patients older than 70, surgical results were slightly superior to stenting (NINDS, 2012).

Carotid endarterectomy has been shown to reduce the risk of TIA and stroke in people with moderate to severe narrowing (70%–99%) of the carotid arteries. Carotid endarterectomy is three times more effective than treatment with medication alone in these patients (WebMD, 2014).

Carotid endarterectomy is recommended for patients with a non-disabling stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) within 6 months and 70% to 99% ipsilateral stenosis when the perioperative rate of major adverse events is <6% (UMHS, 2014).

A carotid endarterectomy can be considered for patients with a non-disabling stroke or TIA within 6 months and 50% to 69% ipsilateral stenosis, based on individual patient factors when the perioperative rate of major adverse events is less than 6% (UMHS, 2014).

Perform carotid endarterectomy as early as judged possible after the stroke or TIA, when risk of another stroke is highest. This benefit of surgery decreases with time (UMHS, 2014).

Carotid stenting is an alternative to carotid endarterectomy when patients are at high risk for surgery or in specific circumstances (e.g., high carotid bifurcation, extensive radiation induced stenosis, prior carotid intervention). The perioperative morbidity and mortality of carotid stenting should be less than 6% (UMHS, 2014).

Other therapies: All patients with carotid disease after stroke should be on optimal medical therapy and have appropriate lifestyle modifications, whether or not an intervention is performed (UMHS, 2014).

Atrial Fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a major risk factor for stroke. As already noted, the 2011 AHA/ASA primary stroke prevention guidelines recommend that ED’s screen for atrial fibrillation and assess patients for anticoagulation therapy if AF is found (Goldstein et al., 2011).

In several trials, oral anticoagulation with warfarin was shown to be superior to aspirin plus clopidogrel for prevention of vascular events in patients with AF who were at high risk for stroke. The Atrial fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial with Irbesartan for prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE W) was stopped early because of clear evidence of the superiority of anticoagulation as opposed to antiplatelet therapy (Connolly et al., 2006).

For patients with AF after stroke or TIA, the 2010 AHA/ASA secondary stroke prevention guidelines are in accord with the standard recommendation of warfarin or other anticoagulant, with aspirin as an alternative for patients who cannot take oral anticoagulants. Clopidogrel should not be used in combination for these patients because the bleeding risk equals that of Coumadin or other anticoagulants, but without the benefits (Wann et al., 2011).

Recognizing Stroke Symptoms

The most common identifying feature of stroke is its acute onset. Every second a clot blocks blood flow to the brain, 32,000 brain cells die. Administration of clot-busting thrombolytic drugs must happen as soon as possible after onset of symptoms to prevent further brain damage. A New York study determined that only 20% of patients arrived at a designated stroke center within 3 hours of stroke symptom onset (the recommended time frame for use of thrombolytics). This study showed that more than 70% of respondents would call 911 if they noticed someone having difficulty speaking, but only 33% would call 911 for double vision or trouble seeing (Jurkowski et al., 2008).

Stroke Symptoms

Source: National Institutes of Health.

The delay between symptom onset and arrival at a hospital is influenced by:

- Identification of stroke symptoms

- Determination that the symptoms require immediate emergency care

- Calling 911

- The time it takes until hospital arrival

Evidence suggests that most of the delay between symptom onset and hospital arrival occurs before the call to 911 is made (Jurkowski et al., 2008).

The CDC, AHA, and ASA, among others, have developed public health programs that emphasize quick recognition of stroke signs and symptoms.In June 1998 the Brain Attack Coalition, a group of professional, volunteer, and government entities dedicated to reducing stroke-related death and disability, reached consensus on the symptoms of stroke. Previously, standardized definitions for stroke signs and symptoms did not exist (Wall et al., 2008, updated 2013).

The consensus symptoms are:

- Sudden numbness or weakness of face, arm, or leg, especially on one side of the body

- Sudden confusion or trouble speaking or understanding speech

- Sudden trouble seeing in one or both eyes

- Sudden trouble walking, dizziness, or loss of balance or coordination

- Sudden severe headache with no known cause

The “suddens” were adopted by several national and state-based educational campaigns and are used to convey stroke symptoms in clinical and public health settings and among advocacy organizations concerned with stroke.

Although consensus on stroke symptoms has been achieved, public awareness has still lagged behind. For example, advocacy organizations in Massachusetts have annually conducted at least one campaign on the signs and symptoms of stroke. Yet in 2003 only 18% of Massachusetts adults were aware of all signs and symptoms of stroke, but 80% said they would call 911 if they thought someone was having a stroke or heart attack. Because early recognition leads to early treatment and improved clinical outcomes, increasing symptom recognition could vastly improve stroke survival and quality of life (Wall, 2008, updated 2013).

To address the lack of recognition of stroke symptoms in their state, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health Heart Disease and Stroke Prevention and Control Program (HSPC) hired a social marketing and communications company to develop an evidence-based approach to educate the public to recognize the signs of stroke and respond by calling 911. The campaign showed that a public awareness campaign that includes mass media can increase stroke recognition but should target family, coworkers, and caregivers of those at highest risk for stroke. Moreover, educational efforts should focus on behaviors that promote early seeking of hospital care (Wall, 2008, updated 2013).

In another instance, the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale (CPSS), a three-item scale based on a simplification of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale was accurately used by untrained laypeople to identify stroke signs in mock patients and in stroke survivors when prompted by a 911 telecommunicator. The CPSS can identify stroke patients who are candidates for thrombolytic treatment when performed by a physician and has similar results when used by prehospital care providers (Wall, 2008, updated 2013).

The CPSS was modified with the addition of a fourth item, so that it could be used by lay people before they called 911. These and other studies lead to the development of the Stroke Heroes Act FAST campaign which, in a retrospective chart review of 3500 stroke patients, successfully identified almost 90% of patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack (Wall, 2008, updated 2013).

Checking for Signs of Stroke

F: Does the face look uneven?

A: Does the arm drift down?

S: Does the speech sound strange?

T: Every second brain cells die. Call 911 at any sign of stroke.

Source: CDC, 2014b.