Assessment and documentation of pain, systematically and consistently, guides the identification of pain as well as the effectiveness of treatment. Since the goal of therapy is to alleviate pain and improve function, assessment should focus on pain and functional status.

The most critical aspect of pain assessment is that it be done on a regular basis using a standard format. Pain should be re-assessed after each intervention to evaluate the effect and determine whether interventions should be modified. The time frame for re-assessment should be directed by the needs of the patient and the hospital or unit policies and procedures.

A self-report by the patient has traditionally been the mainstay of pain assessment. Family caregivers can be used as proxies for patient reports, especially in situations in which communication barriers exist, such as cognitive impairment or language barriers. It is important to note that family members who act as proxies typically, as a group, report higher levels of pain than patient self-reports, although there is individual variation.

Both physiologic and behavioral responses can indicate the presence of pain and should be noted as part of a comprehensive assessment, particularly following surgery. Physiologic responses include tachycardia, increased respiratory rate, and hypertension. Behavioral responses include splinting, grimacing, moaning or grunting, distorted posture, and reluctance to move. A lack of physiologic responses or an absence of behaviors indicating pain may not mean there is an absence of pain.

Good documentation allows communication among clinicians about the current status of the patient’s pain and responses to the plan of care. The Joint Commission requires that pain be documented as a means of prompting clinicians to re-assess and document pain whenever vital signs are obtained. Documentation is also used as a means of monitoring the quality of pain management within the institution.

Pain Assessment Tools

Selecting a pain assessment tool should be, when possible, a collaborative decision between patient and provider to ensure that the patient is familiar with the tool. If the clinician selects the tool, consideration should be given to the patient’s age; physical, emotional, and cognitive status; and personal preferences. Patients who are alert but unable to talk may be able to point to a number or a face to report their pain. The pain tool selected should be used on a regular basis to assess pain and the effect of interventions; it should not, however, be used as the sole measure of pain (AHRQ, 2008).

Pain Scales

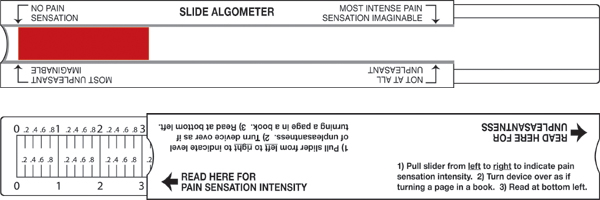

Many pain intensity measures have been developed and validated. Most measure only one aspect of pain (ie, pain intensity) and most use a numeric rating. Some tools measure both pain intensity and pain unpleasantness and use a sliding scale that allows the patient to identify small differences in intensity. The following illustrations show some commonly used pain scales.

Visual Analog Scale

The Visual Analog Scale. The left endpoint corresponds to “no pain” and the right endpoint (100) is defined as “pain as intense as it can be.”

†A 10-cm baseline is recommended for VAS scales.

Source: Adapted from Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel, 1992 (AHCPR, 1994). Public domain.

Numeric Rating Scale

The Numeric Rating Scale. Indicated for adults and children (>9 years old) in all patient care settings in which patients are able to use numbers to rate the intensity of their pain. The NRS consists of a straight horizontal line numbered at equal intervals from 0 to 10 with anchor words of “no pain,” “moderate pain,” and “worst pain.” Source: Adapted from Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel, 1992 (AHCPR, 1994). Public domain.

The Pain Scale for Professionals

The Pain Scale for Professionals. The patient slides the middle part of the device to the right and left and views the amount of red as a measure of pain sensation. The arrow at the left means “no pain sensation” and the arrow at the right indicates the “most intense pain sensation imaginable.” The sliding part of the device is moved on a different axis for the unpleasantness scale. The arrow at the left means “not at all unpleasant” and the arrow at the right represents pain that is the “most unpleasant imaginable.” Source: The Risk Communication Institute. Used with permission.

|

Verbal Rating Scale (VRS) |

|

|---|---|

|

Description |

Points Assigned |

|

No pain |

0 |

|

Mild pain |

2 |

|

Moderate |

5 |

|

Severe |

10 |

Simpler tools such as the verbal rating scale (VRS) classify pain as mild, moderate, or severe. Some studies indicate that older adults prefer to characterize their pain using the VRS. The description can be translated to a number for charting (see following table) and works particularly well if everyone on the unit uses the same scale.

For patients with limited cognitive ability, scales with drawings or pictures, such as the Wong-Baker FACES™ scale, are useful. Patients with advanced dementia may require behavioral observation to determine the presence of pain.

Wong-Baker FACES™ Pain Rating Scale

The Wong-Baker FACES scale is especially useful for those who cannot read English and for pediatric patients. Source: Copyright 1983, Wong-Baker FACES™ Foundation, www.WongBakerFACES.org. Used with permission.

Pain Questionnaires

Pain questionnaires typically contain verbal descriptors that help patients distinguish different kinds of pain. The McGill Pain Questionnaire, developed by Melzack in 1971, asks patients to describe subjective psychological feelings of pain. Pain descriptors such as pulsing, shooting, stabbing, burning, grueling, radiating, and agonizing (and more than seventy other descriptors) are grouped together to convey a patient’s pain response. The McGill Pain Questionnaire combines a list of questions about the nature and frequency of pain with a body-map diagram to pinpoint its location. The questionnaire uses word lists separated into four classes (sensory, affective, evaluative, and miscellaneous) to assess the total pain experience. After patients are finished rating their pain words, the administrator allocates a numerical score, called the “Pain Rating Index.” Scores vary from 0 to 78, with the higher score indicating greater pain (Srouji et al., 2010).

The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), developed by the World Health Organization, also uses the questionnaire format to measure pain. The ability to resume activity, maintain a positive affect or mood, and sleep are relevant functions for patients. The BPI uses a numeric rating scale to assess difficulties with walking, general activity, mood, and sleep.

Assessing Pain in Children

Despite decades of research and the availability of effective analgesic approaches, many children continue to experience moderate to severe pain, especially after hospitalization. Greater research efforts are needed to identify the factors that facilitate effective pain management. Overall, the factors affecting children’s pain management are influenced by cooperation (nurses, doctors, parents, and children), child (behavior, diagnosis, and age), organization (lack of routine instructions for pain relief, lack of time, and lack of pain clinics), and nurses (experience, knowledge, and attitude) (Aziznejadroshan et al, 2016).

Pain evaluation in small children can be a difficult task, since it is a multidimensional experience that possesses sensory and affective components often hard to discriminate by the existing scores. Previous experiences, fear, anxiety, and discomfort may alter pain perception; thus, poor agreement between instruments and raters is often the norm. It has been suggested that, in children younger than 7 years of age and in cognitively impaired children, evaluation of pain intensity through self-report instruments can be inaccurate due to poor understanding of the instrument and poor capacity to translate the painful experience into verbal language; therefore, complementary observational pain measurements should be used to assess pain intensity (Kolosovas-Machuca et al., 2016).

Three methods are commonly used to measure a child’s pain intensity:

- Self-reporting: what a child is saying, using age-appropriate numeric scales, pictorial scales, or verbal scales.

- Behavioral measures: what a child is doing using motor response, behavioral responses, facial expression, crying, sleep patterns, decreased activity or eating, body postures, and movements. These are more frequently used with neonates, infants, and younger children where communication is difficult.

- Physiologic measures: how the body is reacting using changes in heartrate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation, palmar sweating, respiration, and sometimes neuroendocrine responses. They are generally used in combination with behavioral and self-report measures, as they are usually valid for short-duration acute pain and differ with the general health and maturational age of the infant or child. In addition, similar physiologic responses also occur during stress, which results in difficulty distinguishing stress versus pain responses (Srouji et al., 2010).

Children’s capability to describe pain increases with age and experience, and changes throughout their developmental stages. Although observed reports of pain and distress provide helpful information, particularly for younger children, they are reliant on the individuals completing the report (Srouji et al., 2010).

Assessing Pain in Infants

The major challenge with infant pain assessment is that neonates cannot self-report their subjective experience of pain. Moreover, there is a lack of agreement on the best proxy modality of assessing infant pain, whether it is cortical, biochemical, physiologic, or behavioral. Recent work has suggested discordance not only among modalities, but also within an assessment modality. For example, the validity and reliability of physiologic measures of infant pain are presently disputed because these measures are influenced by additional variables that have not been properly taken into account (eg, infection and respiratory rate) (Waxman et al., 2016).

Cardio-physiologic indices of pain, such as heart rate and heart rate variability, are pervasive in the hospital setting. Recently, a group of Canadian researchers looked at the development of cardiovascular responses to acutely painful medical procedures over the first year of life in both preterm and term-born infants. Researchers noted the following:

- Extremely pre-term infants (born at less than 28 weeks gestational age) displayed a blunted heart rate response to acute pain in the first week of life.

- In infants born between 28 and less than 32 weeks gestational age, mean heart rate was found to significantly increase following an acutely painful procedure from birth to four months of age.

- In infants born at 32 to less than 37 weeks gestational age, mean heart rate was found to increase in response to acute pain during the first postnatal week of life; however, the magnitude of responses was variable.

- During the first four postnatal months of life, full-term infants displayed an increase in mean heart rate in response to acute pain; however, the magnitude of responses was variable (Waxman et al., 2016).

The most common pain measures used for infants are behavioral. These measures include crying, facial expressions, body posture, and movements. The quality of these behaviors depends on the infant’s gestational age and maturity. Preterm or acutely ill infants, for example, do not elicit similar responses to pain due to illness and lack of energy. Interpretation of crying in infants is especially difficult, as it may indicate general distress rather than pain. Cry characteristics are also not good indicators in preterm or acutely ill infants, as it is difficult for them to produce a robust cry (Srouji et al., 2010).

Assessing Pain in Toddlers

In toddlers, verbal skills remain limited and quite inconsistent. Pain-related behaviors are still the main indicator for assessments in this age group. Nonverbal behaviors such as facial expression, limb movement, grasping, holding, and crying are considered more reliable and objective measures of pain than self-reports. Most children of this age are capable of voluntarily producing displays of distress, with older children displaying fewer pain behaviors (ie, they cry, moan, and groan less often) (Srouji et al., 2010).

Most 2-year-old children can report the incidence and location of pain, but do not have the adequate cognitive skills to describe its severity. Three-year-old children, however, can start to differentiate the severity of pain, and are able to use a three-level pain intensity scale with simple terms like “no pain,” “little pain” or “a lot.” Children in this age group are usually able to participate in simple dialogue and state whether they feel pain and “how bad it is” (Srouji et al., 2010).

Assessing Pain in Preschoolers

By the age of four years, most children are usually able to use 4- to 5-item pain discrimination scales. Their ability to recognize the influence of pain appears around the age of five years, when they are able to rate the intensity of pain. Facial expression scales are most commonly used with this age group to obtain self-reports of pain. These scales require children to point to the face that represents how they feel or the amount of pain they are experiencing (Srouji et al., 2010).

Assessing Pain in School-Aged Children

Healthcare professionals depend more comfortably on self-reports from school-aged children. Although children at this age understand pain, their use of language to report it is different from adults. At roughly 7 to 8 years of age children begin to understand the quality of pain. Self-report, visual analog, and numerical scales are effective in this age group. A few pain questionnaires have also proven effective for this age (eg, pediatric pain questionnaire, adolescent pediatric pain tool) (Srouji et al., 2010).

Assessing Pain in Adolescents

Adolescents tend to minimize or deny pain, especially in front of friends, so it is important to provide them with privacy and choice. For example, they may or may not choose to have parents present. They expect developmentally appropriate information about procedures and accompanying sensations. Some adolescents regress in behavior under stress. They also need to feel able to accept or refuse strategies and medications to make procedures more tolerable. To assess pain, specifically chronic pain, the adolescent pediatric pain tool (APPT) or the McGill pain questionnaire are helpful (Srouji et al., 2010).

Assessing Pain in Cognitively Intact Adults

For the cognitively intact adult, assessment of pain intensity in the clinical setting is most often done by using the 0 to 10 numeric rating scale or the 0 to 5 Wong-Baker Faces scale, or the VRS. Once patients know how to use a pain intensity scale, they should establish “comfort-function” goals. With the clinician’s input, patients can determine the pain intensity at which they are easily able to perform necessary activities with the fewest side effects.

The American Geriatrics Society (AGS) and the British Geriatrics Society have issued guidelines for the management of pain in older adults, which begins with an accurate assessment and includes the impact of pain on the patient’s daily activities. When analgesic treatment and pain-modulating drugs are used, co-morbidities and other risk factors must be carefully considered. The least invasive method of administration should be used—in most cases the oral route is preferred (Age and Ageing, 2013).

Assessing Pain in Cognitively Impaired Adults

The assessment of pain in patients with cognitive impairment is a significant challenge. Cognitively impaired patients tend to voice fewer pain complaints but may become agitated or manifest unusual or sudden changes in behavior when they are in pain. Caregivers may have difficulty knowing when these patients are in pain and when they are experiencing pain relief. This makes the patient vulnerable to both under-treatment and over-treatment.

In the absence of accurate self-report it has been necessary to develop observational tools to be used in both research and practice, based on the interpretation of behavioral cues to assess the presence of pain. This approach has resulted in a proliferation of pain assessment instruments developed to identify behavioral indicators of pain in people with dementia and other cognitive impairment (Lichtner et al., 2014).

The most structured observational tools are based on guidance published by the American Geriatrics Society, which describe six domains for pain assessment in older adults:

- Facial expression

- Negative vocalization

- Body language

- Changes in activity patterns

- Changes in interpersonal interactions

- Mental status changes (Lichtner et al., 2014)

In people with dementia, the interpretation of these behaviors can be complex due to overlap with other common behavioral symptoms or cognitive deficits such as boredom, hunger, anxiety, depression, or disorientation. This increases the complexity of accurately identifying the presence of pain in patients with dementia and raises questions about the validity of existing instruments (Lichtner et al., 2014).

As a result, there is no clear guidance for clinicians and care staff on the effective assessment of pain, nor how this should inform treatment and care decision-making. A large number of systematic reviews have been published, which analyze the relative value and strength of evidence of existing pain tools. There is a need for guidance on the best evidence available and for an overall comprehensive synthesis (Lichtner et al., 2014).

In a systematic review of reliability, validity, feasibility and clinical utility of 28 pain assessment tools used with older adults with dementia, no one tool appeared to be more reliable and valid than the others (Lichtner et al., 2014). Patient self-report remains the gold standard for pain assessment but in non-verbal older adults the next best option, from a user-centered perspective, becomes the assessment of a person who is most familiar with the patient in their everyday life in a hospital or other care setting; this is sometimes referred to as a “silver standard” (Lichtner et al., 2014).

A thorough review of pain assessment tools for nonverbal older adults by Herr, Bursch, and Black of The University of Iowa is available here.

Keeping these challenges in mind, three commonly used behavioral assessment tools are examples of tools that are used in assessing pain and evaluating interventions in cognitively impaired adults.

Behavioral Pain Scale

The Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS) was developed for use with critically ill patients in the ICU. It evaluates and scores three categories of behavior on a 1 to 4 scale:

- Facial expression: 1 for relaxed to 4 for grimacing

- Upper-limb movement: 1 for no movement to 4 for permanently retracted

- Ventilator compliance: 1 for tolerating ventilator to 4 for unable to control ventilation

A cumulative score above 3 may indicate pain is present; the score can be used to evaluate intervention, but cannot be interpreted to mean pain intensity. The patient must be able to respond in all categories of behavior—for example, the BPS should not be used in a patient who is receiving a neuromuscular blocking agent.

Pain Assessment Checklist

Pain behavior checklists differ from pain behavior scales in that they do not evaluate the degree of an observed behavior and do not require a patient to demonstrate all of the behaviors specified, although the patient must be responsive enough to demonstrate some of the behaviors. These checklists are useful in identifying a patient’s “pain signature”—the pain behaviors unique to that individual.

The Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate (PACSLAC) is a caregiver-administered tool that evaluates sixty behaviors divided into four subscales:

- Facial expressions (13 items)

- Activity/body movements (20 items)

- Social/personality/mood (12 items)

- Physiological indicators/eating and sleeping changes/vocal behaviors (15 items)

A checkmark is made next to any behavior the patient exhibits. The total number of behaviors may be scored but cannot be equated with a pain intensity score. It is unknown if a high score represents more pain than a low score. In other words, a patient who scores 10 out of 60 behaviors does not necessarily have less pain than a patient who scores 20. However, in an individual patient, a change in the total pain score may suggest more or less pain.

Advanced Dementia Scale (PAINAD)

The Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia Scale (PAINAD) was developed to provide a clinically relevant and easy-to-use observational pain assessment tool for individuals with advanced dementia. The aim of the tool developers was to “develop a tool for measuring pain in non-communicative individuals that would be simple to administer and had a score from 0 to 10” (Herr, et al., 2008). This tool is used when severe dementia is present. This tool involves the assessment of breathing, negative vocalization, facial expression, body language, and consolability.

|

Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

0 |

1 |

2 |

Score* |

|

Breathing |

Normal |

|

|

|

|

Negative vocalization |

None |

|

|

|

|

Facial expression |

Smiling or inexpressive |

|

Facial grimacing |

|

|

Body language |

Relaxed |

|

|

|

|

Consolability |

No need to console |

Distracted or reassured by voice or touch |

Unable to console, distract, or reassure |

|

|

PAINAD Scoring: 1-3 = Mild; 4-6 = Moderate; 7-10 = Severe |

Total: |

|||

Clinical Assessment of Cancer Pain

Pain assessment in patients with pain secondary to cancer begins with a thorough discussion of the patient’s goals and expectations for pain management, including balancing pain levels and other patient goals, such as mental alertness. Comprehensive pain assessment also includes pain history, pain intensity, quality of pain, and location of pain. For each pain location, the pattern of pain radiation should be assessed (NCI, 2016).

A review of the patient’s current pain management plan and how he or she has responded to treatment is important. This includes how well the current treatment plan addresses breakthrough or episodic pain. A full assessment also reviews previously attempted pain therapies and reasons for discontinuation; other associated symptoms such as sleep difficulties, fatigue, depression, and anxiety; functional impairment; and any relevant laboratory data and diagnostic imaging. A focused physical examination includes clinical observation of pain behaviors, pain location, and functional limitations (NCI, 2016).

Psychosocial and existential factors that can affect pain must also be assessed and treated. Depression and anxiety in particular can strongly influence the pain experience. Across many different types of pain, research has shown the importance of considering a patient’s sense of self-efficacy over their pain: low self-efficacy, or focus on solely pharmacologic solutions, is likely to increase the use of pain medication (NCI, 2016).

Patients who catastrophize pain (eg, patient reports pain higher than 10 on a 10-point scale) are more likely to require higher doses of pain medication than are patients who do not catastrophize. Catastrophizing is strongly associated with low self-efficacy and reliance on chemical coping strategies. Assessing the impact of pain on the individual’s life and associated factors that exacerbate or relieve pain can reveal how psychosocial issues are affecting the patient’s pain levels (NCI, 2016).

A number of factors can help a provider predict response to pain treatment in a cancer patient. Specifically, a high baseline pain intensity, neuropathic pain, and incident pain are often more difficult to manage. Certain patient characteristics such as a personal or family history of illicit drug use, alcoholism, smoking, somatization, mental health issues such as depression or anxiety, and cognitive dysfunction are associated with higher pain expression, higher opioid doses, and longer time to achieve pain control (NCI, 2016).

Several risk-assessment tools have been developed to assist clinicians, such as the Edmonton Classification System for Cancer Pain (ECS-CP) and the Cancer Pain Prognostic Scale (CPPS) (NCI, 2016).

The ECS-CP considers (1) neuropathic pain, (2) incident pain, (3) psychological distress, (4) addiction, and (5) cognitive impairment. The presence of any of these factors indicates that pain may be more difficult to control. The ECS-CP has been validated in various cancer pain settings. The CPPS (NCI, 2016) considers four variables in a formula to determine the risk score:

- Worst pain severity (Brief Pain Inventory)

- Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G) emotional well-being

- Initial morphine equivalent daily dose (≤60 mg/day; >60 mg/day)

- Mixed pain syndrome

CPPS scores range from 0 to 17, with a higher score indicating a higher possibility of pain relief (NCI, 2016).