One of the most common definitions of pain comes from the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), which describes pain as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage.” When we are exposed to something that causes pain, if able, we quickly or reflexively withdraw. The sensory feeling of pain is called nociception.

In the absence of an objective measure, pain is a subjective individual experience. How a person responds to pain is related to his or her genetic features and cognitive, motivational, emotional, and psychological state. Pain response is also related to gender, experiences and memories of pain, cultural and social influences, and general health (Sessle, 2012).

Factors Influencing the Experience of Pain | |

|---|---|

Physiologic/biologic factors |

|

Psychological factors |

|

Acute Pain

Acute pain comes on quickly and can be severe, but lasts a relatively short time (IOM, 2011). It can be intensely uncomfortable. It usually has a well-defined location and an identifiable painful or noxious stimulus from an injury, brief disease process, surgical procedure, or dysfunction of muscle or viscera. Acute pain alerts us to possible injury, inflammation, or disease and can arise from somatic or visceral structures.

Acute pain is often successfully treated with patient education, mild pain medications, environmental changes, and stress reduction, physical therapy, chiropractic, massage therapy, acupuncture, or active movement programs. Acute pain is usually easier to treat than chronic pain.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has targeted improved treatment of acute pain as an area of significant healthcare savings. The IOM states that better treatment of acute pain, through education about self-management and better clinical treatment, can avoid its progression to chronic pain, which is more difficult and more expensive to treat (IOM, 2011).

Chronic Pain

Chronic pain generally refers to pain that exists for three or more months and does not resolve with treatment. The three-month time frame is not absolute and some conditions may become chronic in as little as a month.

Chronic pain is common; it affects 1 in 5 adults, is more prevalent among women and elders, and is associated with physically demanding work and lower level of education (King & Fraser, 2013). Chronic pain is a silent epidemic that reduces quality of life, negatively impacts relationships and jobs, and increases rates of depression (Sessle, 2012).

Chronic pain is a symptom of many diseases. Up to 70% of cancer patients suffer from chronic pain and, among individuals living with HIV/AIDS, pain has been reported at all stages of infection (Lohman et al., 2010).

Chronic pain is also costly. A 2011 IOM report places this cost at more than $500 billion per year in the United States, creating an economic burden that is higher than the healthcare costs for heart disease, cancer, and diabetes combined. These economic costs stem from the cost of healthcare services, insurance, welfare benefits, lost productivity, and lost tax revenues (Sessle, 2012).

Chronic pain is a multidimensional process that must be considered as a chronic degenerative disease not only affecting sensory and emotional processing, but also producing an altered brain state (Borsook et al., 2007). Chronic pain persists over time and is resistant to treatments and medications that may be effective in the treatment of acute pain.

Aspects of Chronic Pain

When pain becomes chronic, sensory pathways continue to transmit the sensation of pain even though the underlying condition or injury that originally caused the pain has healed. In such situations, the pain itself may need to be managed separately from the underlying condition. Other aspects of chronic pain include:

- Chronic pain may express itself as a consequence of other conditions. For example, chronic pain may arise after the onset of depression, even in patients without a prior pain history.

- Chronic pain patients are often defined as “difficult patients” in that they often have neuropsychologic changes that include changes in affect and motivation or changes in cognition, all of which rarely predate their pain condition.

- In some conditions such as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), manifestations of dysautonomia, movement disorders, and spreading pain (ipsilateral and contralateral) are all indicative of complex secondary changes in the CNS that can follow a relatively trivial peripheral nerve injury.

- Chronic opioid therapy results in a hyperalgesic state (an increased sensitivity to pain) in both experimental and clinical pain scenarios, implying changes in central processing.

- Opioids fail to produce pain relief in all individuals, even at high doses. This implies the development of “analgesic resistance,” a consequence of complex changes in neural systems in chronic pain that complicates the utility of opioids for long-term therapy. (Borsook et al., 2007)

Chronic pain can be difficult to distinguish from acute pain and, not surprisingly, clinicians have less success treating chronic pain than treating acute pain. Chronic pain does not resolve quickly and opioids or sedatives are often needed for treatment, which complicates the clinician-patient relationship. Because medical practitioners often approach chronic pain management from a medication perspective, other modalities are sometimes overlooked.

Chronic pain can affect every aspect of life. It is associated with reduced activity, impaired sleep, depression, and feelings of helplessness and hopelessness, and about one-fourth of people with chronic pain will experience physical, emotional, and social deterioration over time.

Acute pain can progress to chronic pain. Whether this occurs can depend on a number of factors, including the availability of treatment during the acute phase. Factors from birth, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood can also affect whether pain becomes chronic.

Lifespan Factors Affecting the Development of Chronic Pain | |

|---|---|

From birth |

|

Childhood |

|

Adolescence |

|

Adulthood |

|

Musculoskeletal pain, especially joint and back pain, is the most common type of chronic pain (IOM, 2011). Although musculoskeletal pain may not correspond exactly to the area of injury, it is nevertheless commonly classified according to pain location. However, most people with chronic pain have pain at multiple sites (Lillie et al., 2013).

Describing Chronic Pain According to Pathophysiology

When chronic pain is classified according to pathophysiology, three types have been described by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP):

- Nociceptive pain: caused by stimulation of pain receptors

- Neuropathic pain: caused by damage to the peripheral or central nervous system

- Psychogenic pain: caused or exacerbated by psychiatric disorders

Nociceptive pain is caused by activation or sensitization of peripheral nociceptors in the skin, cornea, mucosa, muscles, joints, bladder, gut, digestive tract, and a variety of internal organs. Nociceptors differ from mechanoreceptors, which sense touch and pressure, in that they are responsible for signaling potential damage to the body. Nociceptors have a high threshold for activation and increase their output as the stimulus increases.

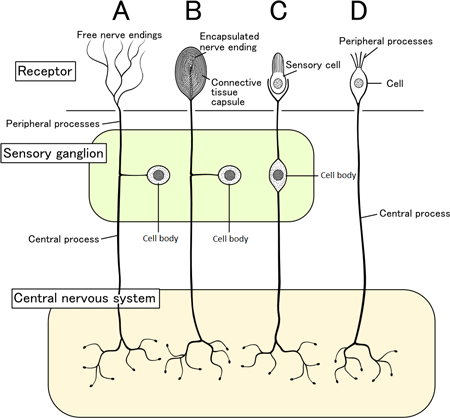

Nociceptors respond to physical stimulation or chemical stimulation. In the physical response, the free nerve endings of the nociceptor (cell A in the diagram below) will become deformed by a sufficiently strong and deep stimulus, and in response send a pain signal. An injury triggers a complex set of chemical reactions as damaged cells release certain chemicals while immune cells reacting to the damage release additional chemicals. The nociceptor is exposed to this chemical “soup,” and continues to send pain signals until the levels of these pain-generating chemicals are lowered over time as the wound heals. A very similar mechanism is at work with itching sensations (Wikiversity, 2015).

Sensory Pathways from Skin to Brain

Schematic of several representative sensory pathways leading from the skin to brain. Source: Shigeru23, Wikimedia Commons.

Neuropathic pain is “pain arising as a direct consequence of a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory system” (IASP, 2012). It is usually described as a poorly localized, electric shock-like, lancinating, shooting sensation originating from injury to a peripheral nerve, the spinal cord, or the brain. It can cause a sensation of burning, pins and needles, electricity, and numbness. Neuropathic pain can be associated with diabetic neuropathy, radiculopathy, post herpetic neuralgia, phantom limb pain, tumor-related nerve compression, neuroma, or spinal nerve compression.

Neuropathic pain is classified as central or peripheral. Central pain originates from damage to the brain or spinal cord. Peripheral pain originates from damage to the peripheral nerves or nerve plexuses, dorsal root ganglion, or nerve roots (IASP, 2012).

Neuropathic pain tends to be long-lasting and difficult to treat. Opioids can be effective, although non-opioid medications such as tricyclic antidepressants, SNRI antidepressants, and several anticonvulsant drugs are commonly used as first-line therapies. Use of SNRIs is common and frequently results in improvement, but treatment of neuropathic pain is considered an off-label use for these agents. Simple analgesics have not been shown to be effective for this type of pain (IASP, 2012).

Psychogenic pain is defined as pain that persists despite the lack of any identified underlying physical cause. Although still commonly used, the term psychogenic pain it is no longer considered an official diagnostic term. A more correct diagnostic term is persistent somatoform pain disorder (PSPD). PSPD is defined in the ICD-10 Version 2016 as

the predominant complaint is of persistent, severe, and distressing pain, which cannot be explained fully by a physiological process or a physical disorder, and which occurs in association with emotional conflict or psychosocial problems that are sufficient to allow the conclusion that they are the main causative influences. The result is usually a marked increase in support and attention, either personal or medical (ICD-10, Version 2016).

Persistent somatoform pain disorder patients suffer from persistent, severe, and distressing pain without sufficient explanatory pathology. It is believed the pain originates from emotional conflicts or psychosocial problems. This type of pain is usually nonresponsive to a variety of therapies because of its unclear pathology. The absence of effective treatment can result in excessive consumption of medical resources, in addition to social problems. Persistent somatoform pain disorder seriously impacts the quality of life of patients and brings a great burden to society (Huang et al, 2016).

The identification of PSPD as having no physiologic cause has done a great deal of damage to individuals with chronic pain. Many healthcare professionals fail to recognize the complexity of pain and believe it can be explained based on the presence or absence of physical findings, secondary gain, or prior emotional problems. As a result, countless individuals have been informed that “the pain is all in your head.” And if these same individuals react with anger and hurt, clinicians sometimes compound the problem by labeling the individual as hostile, demanding, or aggressive (VHA, 2015).

The correspondence between physical findings and pain complaints is fairly low (generally, 40%–60%). Individuals may have abnormal tests (eg, MRI shows a bulging disk) with no pain, or substantial pain with negative results. This is because chronic pain can develop in the absence of the gross skeletal changes we are able to detect with current technology (VHA, 2015).

Muscle strain and inflammation are common causes of chronic pain, yet may be extremely difficult to detect. Other conditions may be due to systemic problems, trauma to nerves, circulatory difficulties, or CNS dysfunction. Yet in each of these cases we may be unable to “see” the cause of the problem. Instead, we have to rely on the person’s report of their pain, coupled with behavioral observations and indirect medical data. This does not mean that the pain is psychogenic or has no underlying physical cause. Instead it means that we are unable to detect or understand its cause (VHA, 2015).

Actually, how often healthy individuals feign pain for secondary gain is unknowable. In addition, the presence of secondary gain does not at all indicate that an individual’s pain is less “real.” In this country most individuals with chronic pain receive at least some type of benefit (not necessarily monetary) for pain complaints. Therefore, exaggeration of pain or related problems is to be expected. Unfortunately, practitioners may use the presence of secondary gain or pain amplification as an indication that the person’s pain is not real (VHA, 2015).

Chronic Pain Syndromes

In deciding how to treat chronic pain, it is important to distinguish between chronic pain and a chronic pain syndrome. A chronic pain syndrome differs from chronic pain in that people with a syndrome over time develop a number of related life problems beyond the sensation of pain itself. It is important to distinguish between the two because they respond to different types of treatment (VHA, 2015).

Most individuals with chronic pain do not develop the more complicated and distressful chronic pain syndrome. Although they may experience the pain for the remainder of their lives, little change in their daily regimen of activities, family relationships, work, or other life components occurs. Many of these individuals never seek treatment for pain and those who do often require less intensive, single-modality interventions (VHA, 2015).

Symptoms of Chronic Pain Syndrome

Those who develop chronic pain syndrome tend to experience increasing physical, emotional, and social deterioration over time. They may abuse pain medications, and typically require more intensive, multimodal treatment to stop the cycle of increasing dysfunction (VHA, 2015).

Symptoms of Chronic Pain Syndrome

Reduced activity

Impaired sleep

Depression

Suicidal ideation

Social withdrawal

Irritability

Fatigue

Memory and cognitive impairment

Poor self-esteem

Less interest in sex

Relationship problems

Pain behaviors

Kinesophobia*

Helplessness

Hopelessness

Alcohol abuse

Medication abuse

Guilt

Anxiety

Misbehavior by children in the home

Loss of employment

* Avoidance of certain movements or activities due to fear of re-injury or re-experiencing the pain.

Source: VHA, 2015.

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) is a general term for a severe chronic neuropathic pain condition that, in the past, was referred to by several other names. Causalgia, from the Greek meaning heat and pain, was the founding term for the syndrome. Causalgia was first used to represent the burning nature of the pain, as seen within American Civil War casualties suffering traumatic bullet wounds (Dutton & Littlejohn, 2015). In the 1940s the term reflex sympathetic dystrophy was introduced when it was thought the sympathetic nervous system played a role in the disease.

In 1994 a working group for the IASP held a conference to develop a more neutral term, to address the widespread inconsistency in terminology, and to avoid unsubstantiated theory on causation and etiology. From this meeting came the officially endorsed term complex regional pain syndrome, intended to be descriptive, general, and not imply etiology. The term was further divided into “CRPS 1” and “CRPS 2.” The current terminology represents a compromise and remains a work in progress. It will likely undergo modifications in the future as specific mechanisms of causation are better defined (Dutton & Littlejohn, 2015).

CRPS I is characterized by intractable pain that is out of proportion to the trauma, while CRPS II is characterized by unrelenting pain that occurs subsequent to a nerve injury. The criteria for diagnosing CRPS is difficult because of the vast spectrum of disease presentations. They can include:

- Intractable pain out of proportion to an injury

- Intense burning pain

- Pain from non-injurious stimulation

- An exaggerated feeling of pain

- Temperature changes in the affected body part

- Edema

- Motor/trophic disturbances, or

- Changes in skin, hair, and nails; and abnormal skin color.

The pain in CRPS is regional, not in a specific nerve territory or dermatome, and it usually affects the hands or feet, with pain that is disproportionate in severity to any known trauma or underlying injury. It involves a variety of sensory and motor symptoms including swelling and edema, discoloration, joint stiffness, weakness, tremor, dystonia, sensory disturbances, abnormal patterns of sweating, and changes to the skin (O’Connell et al., 2013).

The acute phase of the condition is often characterized by edema and warmth and is thought to be supported by neurogenic inflammation. Alterations in CNS structure and function may be more important to the sustained pain and neurocognitive features of the chronic phase of the CRPS (Gallagher et al., 2013).

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) in Hand and Wrist

Source: Wikimedia Commons. Used by permission.

CRPS usually develops following trauma and is thought to involve both central and peripheral components. Continuous pain is the most devastating symptom of CRPS and has been reported to spread and worsen over time. Pain is usually disproportionate to the severity and duration of the inciting event (Alexander et al., 2013).

CRPS has high impact in terms of individual, healthcare, and economic burden, yet continues to lack a clear biologic explanation and predictable, effective treatment. Despite its sizable disease burden, its long history of identification, and a concentrated research effort, many significant challenges remain. These relate to issues of terminology, diagnostic criteria, predisposing factors, triggers, pathophysiology, and the ideal treatment path. There is also the challenge of the well-guarded notion that CRPS is not a true disease state, but rather a condition with psychological foundations (Dutton & Littlejohn, 2015).

While acute CRPS sometimes improves with early and aggressive physical therapy, CRPS present for a period of one year or more seldom spontaneously resolves. The syndrome encompasses a disparate collection of signs and symptoms involving the sensory, motor, and autonomic nervous systems, cognitive deficits, bone demineralization, skin growth changes, and vascular dysfunction (Gallagher et al., 2013).

Although numerous drugs and interventions have been tried in attempts to treat CRPS, relieve pain, and restore function, a cure remains elusive. Two analyses have attempted to develop evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of CRPS. One covers trials in the period between 1980 and June 2005; the second covers the period from June 2000 to February 2012. The earlier review identified the following treatments that had varying degrees of positive therapeutic effect:

- Sub-anesthetic ketamine intravenous infusion

- Gabapentin

- Dimethyl sulphoxide cream

- N-acetylcysteine

- Oral corticosteroids

- Bisphosphonates (eg, alendronate)

- Nifedipine

- Spinal cord stimulation (in selected patients)

- Various physical therapy regimens (Inchiosa, 2013)

Positive findings to varying degrees in the more recent analysis were as follows:

- Low-dose ketamine infusions

- Bisphosphonates

- Oral tadalafil

- Intravenous regional block with a mixture of parecoxib, lidocaine, and clonidine

- Intravenous immunoglobulin

- Memantine 40 mg per day (with morphine)

- Physical therapy

Spinal cord stimulation and transcranial magnetic stimulation improved symptoms, but only transiently (Inchiosa, 2013).

In the past it was common to explain the etiology of complex regional pain syndrome using the psychogenic model. Now however, neurocognitive deficits, neuroanatomic abnormalities, and distortions in cognitive mapping are known to be features of CRPS pathology. More important, many people who have developed CRPS have no history of mental illness. With increased education about CRPS through a biopsychosocial perspective, both physicians and mental health practitioners can better diagnose, treat, and manage CRPS symptomatology (Hill et al., 2012).

Video: What Is Chronic Pain? [2:31]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GTmE5X8NcXM