Despite low-quality evidence supporting practice change, use of chronic opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain increased dramatically over the past two decades. Concurrently, opioid analgesic overdose deaths, addiction, misuse, and diversion have increased markedly.

Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing, 2012

Opioids are chemicals that produce morphine-like effects in the body; they are commonly prescribed for the treatment of both acute and chronic pain and for pain associated with cancer. Opioids have a narcotic effect, that is, they induce sedation and are effective for the management of many types of pain.

Adverse events in opioid therapy can include nausea, vomiting, and constipation, as well as central nervous system (CNS) manifestations such as dizziness, confusion, and sleep disturbance. These directly interfere with patient adherence and are attributed to opioid discontinuation in approximately 25% of patients (Xu & Johnson, 2013).

An estimated 20% of patients presenting to physician offices with noncancer pain symptoms or pain-related diagnoses (including acute and chronic pain) receive an opioid prescription. In 2012 healthcare providers wrote 259 million prescriptions for opioid pain medication, enough for every adult in the United States to have a bottle of pills (CDC, 2016b).

Dozens of compounds fall within this class of opioid analgesics, including hydrocodone, oxycodone, morphine, fentanyl, codeine, propoxyphene (recalled in 2010), hydromorphone (Dilaudid), and meperidine (Demerol). In addition to their effective pain-relieving properties, some of these medications are used to relieve severe diarrhea (eg, Lomotil, or diphenoxylate) or severe coughs (codeine).

Opioid receptors are found throughout the nervous system, as well as in vascular, gut, lung airway, cardiac, and some immune system cells. They act by attaching to specific proteins called opioid receptors. When these drugs attach to their receptors, they reduce the perception of pain (NIDA, 2014a).

There are three types of opioid receptors, with similar protein sequences and structures: mu, delta, and kappa. The mu opioid receptors are thought to give most of their analgesic effects in the CNS, as well as many side effects including sedation, respiratory depression, euphoria, and dependence. Most analgesic opioids are agonists on mu opioid receptors. Of all the analgesics used in pain control, the most safety issues arise with the use of mu opioids, or morphine-like drugs such as morphine, etorphine, methadone, hydromorphone (Dilaudid), sufentanil, and fentanyl.

The delta opioid receptors are more prevalent for analgesia in the peripheral nervous system. The kappa opioid receptors contribute to analgesia in the spine and may cause dysphoria and sedation, but do not generally lead to dependence.

Regulatory agencies and expert groups have encouraged prescribers to rely on evidence-based guidelines when prescribing opioids. This includes:

- Use of opioid treatment agreements

- Regular monitoring for efficacy, safety, and misuse using tools such as urine drug testing and querying prescription monitoring databases and

- Provision of or referral to addiction treatment if recurrent misuse or opioid use disorder is identified (Becker et al., 2016)

In practice, many primary care providers struggle to follow these guidelines, citing lack of clinical time for opioid management, inadequate training, and low confidence. Use of opioid risk mitigation strategies has been low in primary care, even among patients at high risk for misuse. It is therefore understandable that the most complex cases—those in which individuals on long-term opioids, often at high doses, have persistently poor function, exhibit concerning behaviors such as running out of opioids early, or develop a substance use disorder to an opioid or other drug—are extremely challenging to manage in primary care. Even among experts in the field, there is no consensus regarding how to best address these clinical situations (Becker et al., 2016).

Benefits and Harms of Opioid Therapy

Balance between benefits and harm is a critical factor influencing the strength of clinical recommendations. In recent publications, CDC has considered what is known from the epidemiology research about benefits and harms related to specific opioids and formulations, high-dose therapy, co-prescription with other controlled substances, duration of use, special populations, and risk stratification and mitigation approaches (CDC, 2016b).

CDC also considered the number of persons experiencing chronic pain, numbers potentially benefiting from opioids, and numbers affected by opioid-related harms. Finally, CDC considered the effectiveness of treatments that addressed potential harms of opioid therapy (opioid use disorder) (CDC, 2016b).

Specific formulations of opioids have been shown to be harmful. Serious risks have been associated with the use of extended release/long-acting (ER/LA) opioid formulations. ER/LA opioids are used for management of pain severe enough to require daily, around-the-clock, long-term opioid treatment in patients for whom other treatment options such as non-opioid analgesics or immediate-release opioids are ineffective, not tolerated, or would be otherwise inadequate to provide sufficient management of pain. Serious risks have also been associated with time-scheduled opioid use, specifically substantially higher average daily opioid dosage than as-needed opioid use (CDC, 2016b).

Several epidemiologic studies examined the association between opioid dosage and overdose risk related to high-dose therapy. Consistent with the clinical evidence review, opioid-related overdose risk is dose-dependent, with higher opioid dosages associated with increased overdose risk. A study involving Veterans Health Administration patients with chronic pain found that patients who died of overdoses related to opioids were prescribed higher opioid dosages than controls. Another recent study of overdose deaths among state residents with and without opioid prescriptions revealed that prescription opioid-related overdose mortality rates rose rapidly up to prescribed doses of 200 MME/day, after which the mortality rates continued to increase but grew more gradually (CDC, 2016b).

Epidemiologic studies suggest that concurrent use of benzodiazepines and opioids might put patients at greater risk for potentially fatal overdose. Three studies of fatal overdose deaths found evidence of concurrent benzodiazepine use in 31% to 61% of decedents. In one of these studies, among decedents who received an opioid prescription, those whose deaths were related to opioids were more likely to have obtained opioids from multiple physicians and pharmacies than decedents whose deaths were not related to opioids (CDC, 2016b).

Regarding duration of use, patients can experience tolerance and loss of effectiveness of opioids over time. Patients who do not experience clinically meaningful pain relief early in treatment (ie, within 1 month) are unlikely to experience pain relief with longer-term use (CDC, 2016b).

Patients with sleep apnea or other causes of sleep-disordered breathing, patients with renal or hepatic insufficiency, older adults, pregnant women, patients with depression or other mental health conditions, and patients with alcohol or other substance use disorders have been found to have an increased risk for harm from opioids. Opioid therapy can decrease respiratory drive and a high percentage of patients on long-term opioid therapy have been reported to have an abnormal apnea-hypopnea index. Additionally, opioid therapy can worsen central sleep apnea in obstructive sleep apnea patients and it can cause further desaturation in obstructive sleep apnea patients not on continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) (CDC, 2016b).

Reduced renal or hepatic function can lead to a greater peak effect and longer duration of action and reduce the dose at which respiratory depression and overdose occurs. Age-related changes in patients aged ≥65 years, such as reduced renal function and medication clearance, even in the absence of renal disease, result in a smaller therapeutic window for safe dosages. Older adults might also be at increased risk for falls and fractures related to opioids (CDC, 2016b).

Opioids used during pregnancy can be associated with additional risks to both mother and fetus. Some studies have shown an association of opioid use in pregnancy with birth defects, including neural tube defects, congenital heart defects, gastroschisis, preterm delivery, poor fetal growth, and stillbirth. Moreover, in some cases opioid use during pregnancy leads to neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (CDC, 2016b).

Patients with mental health comorbidities and patients with a history of substance use disorders might be at higher risk than other patients for opioid use disorder. Recent analyses found that depressed patients were at higher risk for drug overdose than patients without depression, particularly at higher opioid dosages, although investigators were unable to distinguish unintentional overdose from suicide attempts. In case-control and case-cohort studies, substance abuse/dependence was more prevalent among patients experiencing overdose than among patients not experiencing overdose (CDC, 2016b).

Prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs) and urine drug testing provide potential benefits, including the ability to identify patients who might be at higher risk for opioid overdose or opioid use disorder. These strategies may help determine which patients will benefit from greater caution and increased monitoring or interventions when risk factors are present. One study found that most fatal overdoses could be identified retrospectively on the basis of two pieces of information: multiple prescribers and high total daily opioid dosage. Both of these important risk factors for overdose are available to prescribers in the PDMP. However, limited evaluation of PDMPs at the state level has revealed mixed effects on changes in prescribing and mortality outcomes (CDC, 2016b).

There is limited evidence available regarding the benefits and harm of risk mitigation approaches. Although no studies were found to examine prescribing of naloxone with opioid pain medication in primary care settings, naloxone distribution through community-based programs providing prevention services for substance users has been demonstrated to be associated with decreased risk for opioid overdose death at the community level (CDC, 2016b).

Concerns have been raised that prescribing changes such as dose reduction might be associated with unintended negative consequences, such as patients seeking heroin or other illicitly obtained opioids or interference with appropriate pain treatment. With the exception of a study noting an association between an abuse-deterrent formulation of OxyContin and heroin use, showing that some patients in qualitative interviews reported switching to another opioid, including heroin, for many reasons, including cost and availability as well as ease of use, CDC did not identify studies evaluating these potential outcomes (CDC, 2016b).

Finally, regarding the effectiveness of opioid use disorder treatments, methadone and buprenorphine for opioid use disorder have been found to increase retention in treatment and to decrease illicit opioid use among patients with opioid use disorder involving heroin. Although findings are mixed, some studies suggest that treatment effectiveness is enhanced when psychosocial treatments are used in conjunction with medication-assisted therapy; for example, by reducing opioid misuse and increasing retention during maintenance therapy, and improving compliance after detoxification (CDC, 2016b).

Opioid-Induced Hyperalgesia

Apart from potential side effects, tolerance, and addiction, opioid use can be associated with opioid-induced hyperalgesia, which is defined as a state of nociceptive sensitization caused by exposure to opioids. It is characterized by a paradoxical response whereby a patient receiving opioids for the treatment of pain actually becomes more sensitive to pain (Suzan et al., 2013).

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia in the post operative period has been reported following the administration of short-acting opioids during surgery. Additional evidence comes from opioid addicts on methadone maintenance therapy, in whom decreased tolerance to cold pain has been reported. Mixed results are found regarding hyperalgesia in patients with chronic pain who receive intermediate-term opioid treatment (Suzan et al., 2013).

Opioid Reassessment

In an effort to support primary care in the management of patients with complex chronic pain on long-term opioid therapy, a multi-disciplinary team designed the Opioid Reassessment Clinic (ORC) at VA Connecticut Healthcare System (Becker et al., 2016).

Located in the primary care setting, the clinic is staffed by an addiction psychiatrist, an internist with addiction and pain training, a behavioral health advanced practice nurse, and a clinical health psychologist. The clinic has served as a learning opportunity for management of complex chronic pain and opioids over the past three years. The following case highlights evidence-based practices as well as approaches based on pragmatic considerations where evidence is lacking (Becker et al., 2016).

Case

This is a 56-year-old patient with bilateral hip pain due to severe osteoarthritis that significantly interfered with functioning, for which the patient was prescribed morphine for several years. Nine months prior to Opioid Reassessment Clinic (ORC) referral, the patient successfully completed a residential treatment program for his long-standing alcohol use disorder while continuing on long-term opioid therapy. Presently, the primary care provider referred the patient to the ORC after two episodes of running out of opioid prescriptions early (without early refill) and a brief return to alcohol use.

In the ORC, clinicians facilitated engagement in outpatient alcohol treatment by making continued opioid therapy contingent upon adherence with followup, and required frequent ORC visits including breathalyzer tests and urine drug screens. Following another return to drinking, the patient was admitted to an intensive outpatient alcohol use disorder treatment program and was simultaneously tapered off morphine, transitioning to tramadol with adjuvant non-opioid medications including an NSAID, gabapentin, and topical lidocaine.

While tramadol, a weak mu receptor agonist with more prominent serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition, was still a risky medication in this patient in recovery, it is classified by the DEA as less risky (schedule V compared to oxycodone and morphine’s schedule II designation); plus the patient’s tramadol dose was markedly lower in terms of morphine-equivalent daily dose.

Additionally, orthopedics was consulted and agreed to schedule hip replacement surgery contingent upon several months of documented alcohol abstinence. This motivated the patient to adhere to appointments and monitoring as required by both ORC and addiction treatment providers.

While the patient continued to request a switch to a “stronger” opioid, the ORC repeatedly reiterated that this was not an option given the recent history of misuse, the lack of evidence of improved functioning on such medications, and benefit of being on the lowest possible opioid dose prior to surgery. After 6 months of abstinence from alcohol, safe use of tramadol, and engagement in multimodal therapy including ongoing specialty treatment, the patient was discharged from ORC to followup with primary care providers while awaiting scheduled surgery.

Epilogue: The patient underwent total hip replacement and received 2 weeks of full agonist opioid treatment (MSIR 15 mg Q6 PRN) following the surgery. After the 2-week post-operative period, the patient was transitioned back to tramadol. He remains abstinent from alcohol and participates fully in his hip rehabilitation program.

Source: Becker et al., 2016.

Tolerance, Dependence, and Addiction

Thirty years ago, I attended medical school in New York. In the key lecture on pain management, the professor told us confidently that patients who received prescription narcotics for pain would not become addicted.

While pain management remains an essential patient right, a generation of healthcare professionals, patients, and families have learned the hard way how deeply misguided that assertion was. Narcotics—both illegal and legal—are dangerous drugs that can destroy lives and communities.

Thomas Frieden, MD

Director, CDC

A number of terms and definitions are regularly used to define behaviors that are associated with the misuse and abuse of drugs. These terms are imprecise and at times confusing and can reflect societal attitudes and beliefs about drug abuse. So it is not surprising that medical terminology associated with drug use and abuse is opaque and at times unclear, particularly in the area of prescription drug abuse.

To address this issue and to clarify the terms dependence and addiction, particularly in opioid-treated patients, new definitions for drug addiction have been included in the 2013 DSM-V update. The term “substance dependence”—used in DSM-III and DSM-IV—has been replaced by the terms “substance use disorder” and “opioid use disorder” (IASP, 2013).

Additional changes in the DSM-V state that two items (not including tolerance and withdrawal) are needed from a list of behaviors suggesting compulsive use to meet the criteria for substance use disorder (SUD). Tolerance and withdrawal are not counted for those taking prescribed medications under medical supervision such as analgesics, antidepressants, anti-anxiety medications, or beta-blockers (IASP, 2013).

Tolerance

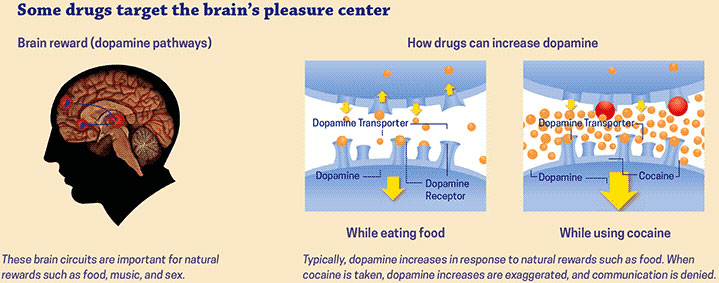

Tolerance is a state of adaptation in which a drug becomes less effective over time, which means a larger dose is needed to achieve the same effect. Tolerance occurs because some drugs cause the brain to release 2 to 10 times the amount of dopamine than natural rewards do. In some cases, this occurs almost immediately—especially when drugs are smoked or injected—and the effects can last much longer than those produced by natural means. The resulting effects on the brain’s pleasure circuit dwarfs those produced by naturally rewarding behaviors.

Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2018.

The Brain’s Reward Circuit

The limbic system—the brain’s reward circuit. Source: National Institute on Drug Abuse.

The brain adapts to these overwhelming surges in dopamine by producing less dopamine or by reducing the number of dopamine receptors in the reward circuit. This reduces the user’s ability to enjoy not only the drugs but also other events in life that previously brought pleasure. This decrease compels the person to keep abusing drugs in an attempt to bring the dopamine function back to normal, but now larger amounts of the drug are required to achieve the same dopamine high (NIDA, 2016a).

Dependence

Dependence is a state of adaptation characterized by symptoms of withdrawal when a medication is abruptly stopped, the dose is rapidly reduced, or an antagonist is administered. It is a term often misused as a synonym for addiction, but the two terms are not synonymous. The seriousness of the withdrawal symptoms depends upon the drug being used and the extent of its use (risks increase with higher doses over long periods of time). For some drugs, such as alcohol or benzodiazepines, withdrawal symptoms can be serious and life-threatening.

An example of dependence is a patient who is on morphine for several months for chronic back pain. If the morphine is discontinued all at once, a flu-like syndrome will quickly develop, accompanied by nausea, stomach pains, and malaise. These symptoms of physical dependence will disappear if the morphine is resumed. Once a person has been on opioids for a period of time, the medication must be tapered off to avoid withdrawal symptoms.

Addiction

It is often said that addiction is easy to recognize, that it rarely arises during the treatment of pain with addictive drugs, and that cases of addiction during pain treatment can be managed in much the same way as other addictions, but such generalizations grossly oversimplify the real situation.

International Association for the Study of Pain

Addiction is defined as a chronic, relapsing disease that is characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use, despite the known, harmful consequences. Addiction involves a psychological craving and is considered a brain disease because drugs change the brain’s structure and function. Brain changes can be long lasting and can lead to the harmful behaviors seen in people who abuse drugs. Although taking drugs at any age can lead to addiction, research shows that the earlier a person begins to use drugs the more likely they are to progress to more serious abuse (NIDA, 2014c).

Addiction

The term addiction may be regarded as equivalent to severe substance use disorder as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5, 2013) (NIDA, 2014c).

Opioids are highly addictive and rates of addiction among patients receiving opioids for the management of pain vary from 1% to 50%, which suggest uncertainty about what addiction really is and how often it occurs (IASP, 2013). Savage and colleagues introduced the four “Cs” criteria for identifying opioid addiction in chronic pain population:

- Impaired Control over drug use

- Compulsive use

- Continued use despite harm

- Unmanageable drug Craving (Chang & Compton, 2013).

A strategy to distinguish between aberrant or misuse behaviors and addiction in chronic pain patients is to assess the relationship between opioid dose titration and functional restoration. In this approach, in response to aberrant “drug-seeking” behaviors (ie, continued complaints of pain or requests for more medication), the clinician increases the opioid dose in an effort to provide analgesia. Improvements in functional outcomes and quality of life, with fewer problematic behaviors, indicate that active addiction is not present. In this case, drug-seeking behaviors may reflect pseudo-addiction, therapeutic dependence, or opioid tolerance. Effective dosing results in functional restoration (Chang & Compton, 2013).

Treating Patients with a History of Substance Abuse

Treating chronic pain with chronic opioid therapy in individuals with a history of a substance use disorder (SUD), whether active or in remission, presents a challenge to pain clinicians. This is, in part, due to concerns about the patient relapsing to active substance abuse. In addition, clinicians may confuse “drug-seeking” behaviors with addictive disease, resulting in poor treatment outcomes, such as premature discharge of patients from pain care (Chang & Compton, 2013).

The goal of chronic pain treatment in patients with SUDs is the same as that for patients without SUDs: specifically, to maximize functionality while providing pain relief. However, reluctance to prescribe opioids and poor understanding of the complex relationship between pain and addiction often results in undertreated pain in this population (Chang & Compton, 2013).

When estimating the presence of substance use disorder in chronic pain patients, terminology is important. It is increasingly understood that SUD cannot be defined by physical dependence and tolerance, as these are predictable physiologic consequences of chronic opioid use. Reflecting this, in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-V), tolerance and withdrawal are not counted as criteria for the substance use and addictive disorder diagnosis if a patient is taking an opioid analgesic under medical supervision (Chang & Compton, 2013).

A systematic review of literature synthesizing 21 studies published prior to February 2012 showed that the overall prevalence of current substance use disorders in chronic pain patients ranges from 3% to 48% depending on the population sampled. The lifetime prevalence of any substance use disorder ranged from 16% to 74% in patients visiting the ED, with those visiting for opioid refill having the highest rate. It has been reported that 3% to 11% of chronic pain patients with a history of substance use disorder may develop opioid addiction or abuse, whereas only less than 1% of those without a prior or current history of SUD develop the same (Chang & Compton, 2013).

When screening patients for a history of substance abuse, one of the easiest tools to use is the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Drug Use Screening Tool. It begins with a Quick Screen, which recommends that clinicians ask their patients one question: “In the past year, how often have you used alcohol, tobacco products, prescription drugs for nonmedical reasons, or illegal drugs?” Patients are asked to respond on a 5-point continuum: never, once or twice, monthly, weekly, or daily/almost daily. A response of “at least 1 time” when asked about frequency of prescription or illegal drug use is considered a positive result. Recent research has identified that this single-question screening test is highly sensitive and specific for identifying drug use and drug use disorders (NIDA, 2014a).

For those who screen positive for illicit or nonmedical prescription drug use, clinicians are directed to administer the full NIDA-modified Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (NM-ASSIST). The NM-ASSIST automatically generates a risk level to indicate the level of intervention needed and provides additional resources such as scripts on how to discuss drug use with patients and resources to link patients to specialty care (NIDA, 2016b).

|

Identifying Risk Level |

|

|---|---|

|

High risk Score ≥27 |

|

|

Moderate Risk Score 4–26 |

|

|

Low Risk Score 0–3 |

|

Untreated Addiction

In many primary care or pain management settings, the ability to provide the comprehensive services necessary to treat patients with both pain and current addiction are sorely lacking. Some clinicians strongly believe that patients with chronic pain and active addiction, regardless of type of substance abused, are not candidates for chronic opioid therapy (Chang & Compton, 2013).

Patients with an active substance use disorder should be referred to formal addiction treatment. It is incumbent upon the prescribing clinician to maintain a referral network of substance abuse treatment providers willing to collaborate on providing care to patients with co-morbid pain and substance use disorder. After referral, a pain clinician should continue to work closely with the SUD treatment provider to monitor use behaviors and pain outcomes (Chang & Compton, 2013).

Addiction in Remission

For individuals with addiction in remission, the goal of treatment is the same as that as for all chronic pain patients: to improve pain and maintain functionality. Indicators of successful pain management include:

- The patient’s ability to comply with regimens

- The ability to engage in cognitive-behavioral pain management strategies

- Utilization of positive coping skills to manage stress and

- The ability to establish better social support systems (Chang & Compton, 2013)

Management of co-morbid neuropsychiatric complications is critical to maximize functionality (Chang & Compton, 2013).

Regardless of the type of substance previously abused, exposure to psychoactive medications can lead to relapse in patients with a recently or poorly treated substance use disorder. Although concerns of relapse may contribute to clinicians’ reluctance to prescribe chronic opioid therapy for patients whose addiction is in remission, there is evidence that patients with successfully treated addiction can be effectively treated with opioids for chronic pain (Chang & Compton, 2013).

In patients with substance use disorder in remission, clinicians must assess the patient’s relative risk for relapse and monitor for its emergence. The ability to manage a relapse episode is a necessary skill of any chronic opioid therapy prescriber. To assess risk of relapse, a series of questions should be asked of the chronic pain patient regarding the status of SUD remission. Asking these questions at each visit allows for early identification of high-risk situations and potential coping responses to these stressors (Chang & Compton, 2013).

- How long you been in recovery?

- How engaged are you in addiction recovery efforts and treatment (ie, supportive counseling, 12-step program)?

- What types of drugs have you abused?

- What are current stressors that might precipitate relapse (unrelieved pain, sleep disorders, withdrawal symptoms, psychiatric symptoms, interpersonal conflicts)?

- What are your current protective factors against relapse, including improved coping responses and a social support system?

- How stable you feel in recovery? (Chang & Compton, 2013)

A relapse contract can be developed early in treatment, which is individualized to the patient and specifies steps or actions that will be taken by both the patient and clinician if relapse occurs. The patient’s behaviors with respect to the opioid analgesic regimen provide the best evidence for the presence of active addiction (Chang & Compton, 2013)

The clinician should keep in mind that seeking a higher dose of a prescribed medication does not necessarily mean that the patient is drug-seeking. However, losing or forging prescriptions, stealing or having others steal for you, visiting multiple providers for duplicate prescriptions, and injecting oral formulations are signs that the patient is not using the medication appropriately.

Management of pain requires a great degree of trust on both sides. Being consistent, open, and fair are important attributes for the provider. Providing positive feedback, reducing harm through education, and attempting to understand individual circumstances are helpful to the patient. If the patient is approaching the end of life, old habits and fears often resurface and more support may be needed.

Children and Opioids

Thankfully, not many children experience the types of cancer pain, extensive trauma, or surgeries that require long-term pain management. However, few pain management products have specific information on their label about their safety and effectiveness in pediatric patients. This even includes several new pain medications that have been approved for use in adults.

To manage pain in pediatric patients, physicians often have to rely on their own experience to interpret and translate adult data into dosing information for pediatric patients.

Sharon Hertz, MD, Director

FDA, Office of New Drugs

Center for Drug Evaluation and Research,

Division of Anesthesia, Analgesia, and Addiction Products

The use of opioids to treat pain in infants and children presents challenges. First, with rare exceptions, opioids have not been labeled for use in individuals under 18 years of age. There is a dearth of quality studies on pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, and clinical effectiveness. Acute pain problems in pediatrics have many characteristics in common with adult presentations. Persistent, recurrent, and chronic pain in infants, children, and adolescents are often qualitatively different from chronic pain problems in adults. Treatment approaches may vary accordingly (Oregon Pain Guidance, 2016).

In adults, there is a well-recognized epidemic of hospitalizations and deaths related to the increasing use of opioid analgesics. Although there are fewer studies in children, this vulnerable population also appears to be at high risk for opioid toxicity. A study of 960 randomly selected medical records from 12 children’s hospitals in the United States identified 107 adverse drug events with more than half attributable to opioid analgesics. Deaths have been reported in young children related to therapeutic use of codeine and hydrocodone in doses within or moderately exceeding recommended pediatric limits (Chung et al., 2015).

Despite their potential for serious adverse events, opioids are increasingly prescribed for adolescents. Opioid prescriptions for patients between 15 and 19 years of age doubled from 1994 to 2007, with estimates that opioids are prescribed in nearly 6% of ambulatory and emergency department visits made by adolescents in the United States (Chung et al., 2015).

Given the large number of pediatric patients receiving prescribed opioids, there is an urgent need for fundamental epidemiologic studies to inform the risk-benefit decisions of prescribers and families. An essential component of these studies is the identification of serious adverse reactions related to opioids. Epidemiologic studies in adults have developed procedures to identify hospitalizations and deaths related to opioid use. However, similar studies in children are lacking (Chung et al., 2015).

Clinical recommendations for chronic non-malignant pain in children and adolescents include (Walco, 2015):

- Prescribe opioids for acute pain in infants and children only if knowledgeable in pediatric medicine, developmental elements of pain systems, and differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in young children.

- Avoid opioids in the vast majority of chronic nonmalignant pain problems in children and adolescents, as evidence shows no indication.

- Opioids are indicated for a small number of persistent painful conditions, including those with clear pathophysiology and when an endpoint to usage may be defined.

- Opioids may be indicated for some chronic pain conditions in children and adolescents, when there is clear pathophysiology, and no definable endpoint.

- Consult or refer to a pediatric pain specialist when chronic pain problems in children and adolescents are complicated or persistent.

Managing Cancer Pain with Opioids

The use of opioids for the relief of moderate to severe cancer pain is considered necessary for most patients. For moderate pain, weak opioids such as codeine or tramadol or lower doses of strong opioids such as morphine, oxycodone, or hydromorphone are often administered and frequently combined with non-opioid analgesics. For severe pain, strong opioids are routinely used. Although no agent has shown itself to be more effective than any other agent, morphine is often considered the opioid of choice because of provider familiarity, broad availability, and lower cost. In one well-designed review, most individuals with moderate to severe cancer pain obtained significant pain relief from oral morphine (NCI, 2016).

Effective pain management requires close monitoring of patient response to treatment. In a review of 1,612 patients referred to an outpatient palliative care center, more than half of patients with moderate to severe pain did not experience pain relief after the initial palliative care consultation. In addition, one-third of patients with mild pain progressed to moderate to severe pain by the time of their first followup visit (NCI, 2016).

For patients with a poor pain prognosis, clinicians may consider discussing realistic goals for alleviating pain, focusing on function, and use of multimodality interventions. Repeated or frequent escalation of analgesic doses without improvement of pain may trigger clinicians to consider an alternative approach to pain (NCI, 2016).