Despite the difficulty in classifying and understanding various mechanisms of pain, certain pain syndromes are pervasive. Low back pain, headache pain, post operative pain, cancer pain, and pain associated with arthritis are some of the most common reasons patients seek medical care for pain. A National Health Interview Survey of adults during 1997–2014 found that in the three months prior to an interview, participants reported:

- 28% had experienced pain in the lower back

- 16% had experienced a migraine or severe headache

- 14% had experienced pain in the neck area (NCHS, 2016)

Low Back Pain

Low back pain (LBP) is one of the most common types of disability affecting individuals in Western countries. Low back pain affects approximately 80% of people at some stage in their lives, and if it becomes chronic it often results in lost wages and additional medical expenses and can increase the risk of incurring other medical conditions (Chou et al., 2016). Chronic low back pain has been estimated to cost 2% of the gross domestic product in developed countries (Sit et al., 2015).

In the United States, the total indirect and direct costs due to low back pain are estimated to be greater than $100 billion annually (Wang et al., 2012). It is the fifth most common reason for all physician visits. Approximately one-quarter of U.S. adults reported having low back pain lasting at least 1 day in the past 3 months, and 7.6% reported at least one episode of severe low back pain in the previous year.

Clinically, the natural course of low back pain is usually favorable; acute low back pain frequently disappears within 1 to 2 weeks. In some cases acute low back pain becomes chronic and difficult to treat. Any of the spinal structures, including intervertebral discs, facet joints, vertebral bodies, ligaments, or muscles could be an origin of back pain, which is, unfortunately, difficult to determine. In those cases in which the origin of back pain cannot be determined, the diagnosis given is nonspecific low back pain (Aoki et al., 2012).

Assessing Low Back Pain

The vast majority of low back pain patients who present to primary care have pain that cannot be reliably attributed to a specific disease or spinal abnormality. Spinal imaging abnormalities such as degenerative disc disease, facet joint arthropathy, and bulging or herniated intervertebral discs are extremely common in patients with or without low back pain, particularly in older adults, and such findings are poor predictors for the presence or severity of low back pain (Chou et al., 2016).

Low back pain symptoms can arise from many anatomic sources, such as nerve roots, muscle, fascia, bones, joints, intervertebral discs, and organs within the abdominal cavity. Symptoms can also be caused by aberrant neurologic pain processing, a condition called neuropathic low back pain. The diagnostic evaluation of patients with low back pain can be challenging and requires complex clinical decision-making. Nevertheless, the identification of the source of the pain is of fundamental importance in determining the therapeutic approach (Allegri et al., 2016).

The location of pain, frequency of symptoms, duration of pain, history of previous symptoms, previous treatments, and response to treatment should be assessed. The possibility of low back pain due to pancreatitis, nephrolithiasis, or aortic aneurysm, or systemic illnesses such as endocarditis or viral syndromes, should also be considered. Low back pain can be influenced by psychological factors, such as stress, depression, or anxiety. History should include substance use exposure, detailed health history, work habits, and psychosocial factors (Allegri et al., 2016).

Back pain can be referred or felt at a site distant from the source of the pain. Pain can be local or referred from a painful stimulus occurring in an internal organ. An example of referred pain is when a heart attack occurs and pain in felt in the jaw, shoulder, or arm.

Pain may also be felt in the territory of a dermatome, an area of skin supplied by a single sensory nerve. This is referred to as radiating pain and can be quite confusing for patients. If the nerve root is irritated or inflamed, pain can be evoked by any motion that stretches or compresses the root of the nerve. This is referred to as radicular pain, which can occur in patients with serious or progressive neurologic deficits or underlying conditions requiring prompt evaluation, as well as patients with other conditions that may respond to specific treatments.

Patients with back and leg pain have a fairly high sensitivity for herniated disc, with more than 90% of symptomatic lumbar disc herniation occurring at the L4/L5 and L5/S1 levels. A focused examination that includes straight leg–raise testing and a neurologic examination that includes evaluation of knee strength and reflexes (L4 nerve root), great toe and foot dorsiflexion strength (L5 nerve root), foot plantar flexion and ankle reflexes (S1 nerve root), and distribution of sensory symptoms should be done to assess the presence and severity of nerve root dysfunction.

Imaging tests such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be considered only in the presence of clinical elements that are not definitely clear or in the presence of neurologic deficits or other medical conditions. The recommendation of the American College of Radiology is to not do imaging for low back pain within the first 6 weeks unless red flags are present. Red flags include recent significant trauma or milder trauma at age older than 50 years, unexplained weight loss, unexplained fever, immunosuppression, history of cancer, intravenous drug use, prolonged use of corticosteroids, osteoporosis, age older than 70 years, and focal neurologic deficits with progressive or disabling symptoms (Allegri et al., 2016).

Treating Low Back Pain

Despite the negative impact and increasing prevalence of low back pain, patients are regularly ignored and their complaints are often misunderstood. As a result, they often do not receive timely or effective treatment. This issue poses considerable challenges and frustrations for healthcare providers and can create a feeling of mistrust among patients. Ample evidence demonstrates that clinicians’ attitudes and beliefs regarding low back pain seem to affect the beliefs of their patients. Physicians’ attitudes and beliefs also appear to influence their recommendations regarding activities and work (Sit et al., 2015).

Multiple treatment options for acute and chronic low back pain are available. Broadly, these can be classified as pharmacologic treatments, noninvasive nonpharmacologic treatments, injection therapies, and surgical treatments. Pharmacologic treatments include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) drugs, acetaminophen, opioids, muscle relaxants, anti-seizure medications, antidepressants, and corticosteroids (Chou et al., 2016).

Nonpharmacologic treatments include exercise and related interventions, complementary and alternative therapies, psychological therapies, physical modalities, low-level laser therapy, interferential therapy, superficial heat or cold, back supports, and multidisciplinary rehabilitation (Chou et al., 2016).

Migraine Headaches

A migraine is a very painful headache thought to result from vasodilation of blood vessels in the brain. Migraines cause intense, pulsing or throbbing pain on one or possibly both sides of the head. People with migraine headaches often describe pain in the temples or behind one eye or ear. Migraine sufferers may also have symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and sensitivity to light and sound. Some people see spots or flashing lights or have a temporary loss of vision that forewarn of an impending headache. If a migraine occurs more than 15 days each month for 3 months, it is considered chronic.

Migraines often start in the morning, and the pain can last from a few hours up to two days. These headaches can occur as often as several times per week for some patients or as infrequently as once or twice a year. For many with migraines, the quality of life and activity is greatly diminished during attacks, and their frequency can interfere with the ability to work or to perform activities of daily living. Migraine headaches are still under-diagnosed and under-treated because they can have features in common with other types of headache.

Over time, episodes of migraine headache afflict patients with increased frequency, longer duration, and more intense pain. While episodic migraine may be defined as 1 to 14 attacks per month, there are no clear-cut phases defined, and those patients with low frequency may progress to high frequency episodic migraine and the latter may progress into chronic daily headache (>15 attacks per month) (Maleki et al., 2011).

Numerous imaging studies of migraine patients have described multiple changes in brain functions as a result of migraine attacks: these include enhanced cortical excitability, increased gray matter volume in some regions and decreased in others, enhanced brain blood flow, and altered pain modulatory systems (Maleki et al., 2011).

Migraine has no cure. Drug therapies are broadly divided into two groups: (1) those designed to treat acute occurrences, and (2) those that are prophylactic (preventive) in nature. Many people with migraine use both forms of treatment. The goal is to treat migraine symptoms as soon as possible and to minimize the number of migraine occurrences by avoiding triggers.

The treatment of an individual migraine attack once it has occurred (“acute treatment”), is commonly referred to as abortive therapy. Four major medications are used for abortive therapy:

- The triptans

- Ergotamine

- Dihydroergotamine

- Midrin, a combination of isometheptene mucate, dichloralphenazone, and acetaminophen

Other medications include CGRP receptor antagonists and, among herbals, feverfew.

For relatively mild migraine symptoms, over-the-counter (OTC) pain medications such as aspirin, acetaminophen (Tylenol), or NSAIDs like ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), may be sufficient. Some combination medicines are sold specifically for migraines (eg, Excedrin Migraine, which contains aspirin, acetaminophen, and caffeine) but these are usually not strong enough for severe migraines. The patient needs to understand that taking migraine medications more than 3 days a week may lead to rebound headaches—headaches that keep coming back, in part because of the medications.

Many migraine medicines work by narrowing blood vessels to counteract vasodilation in the vessels of the brain. Caution is advised if the patient has risk for heart attacks or has heart disease. Ergots should not be given if the patient is pregnant or planning to become pregnant.

Pain Following Surgery

Pain following surgery is very common. In the United States, nearly 100 million surgeries take place annually—about 46 million inpatient and about 53 million outpatient procedures. Good post surgical pain management is associated with patient satisfaction, earlier mobilization, shortened hospital stays, and reduced costs.

Post operative pain can be caused by tissue damage, the presence of drains and tubes, post operative complications, prolonged time in an awkward position, or a combination of these factors. Post operative pain is often under-estimated and under-treated, leading to increased morbidity and mortality, mostly due to respiratory and thromboembolic complications, increased hospital stay, and impaired quality of life (EAU, 2013).

There is a pressing need for improvements in post operative pain management—about 70% of post surgical patients report pain that is moderate, severe, or extreme (EAU, 2013) and fewer than half of those patients report adequate post surgical pain control (IOM, 2011). Failure to adequately control post operative pain drives up costs and is thought to be a factor in the development of chronic pain (Chapman et al., 2012).

Good post operative pain management requires good pain assessment and measurement in all post operative patients. Assessment should focus on the patient’s response to surgery as well as respiratory and cardiac complications. Assessment should occur at scheduled intervals, in response to new pain, and prior to discharge (EAU, 2013).

Although much of the focus on post operative pain management is on hospitals, about 60% of surgical procedures in community hospitals are performed on an outpatient basis, and persistent problems exist with pain management after discharge (IOM, 2011). This may be because there is not enough time to assess post surgical pain prior to discharge or to establish a pain management program at home.

Psychological factors such as anxiety and depression can be important predictors in the development of post operative pain. Age has also been found as a predictor, with younger individuals being at higher risk for moderate to intense pain. Patients at high risk for severe post operative pain should be provided with special attention. Patients with good analgesia are more cooperative, recover more rapidly, and leave the hospital sooner. They also have a lower risk for prolonged pain after surgery (Ene et al., 2008).

Persistent Post Surgical Pain

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) refers to post operative pain that continues for more than 2 months and cannot be explained by other causes “persistent post surgical pain” (Kehlet & Rathmell, 2010). A percentage of post operative patients (10%–50%) develop persistent pain following common surgical procedures such as groin hernia repair, breast and thoracic surgery, leg amputation, and coronary artery bypass surgery, often due to nerve damage during the procedure (IOM, 2011).

Many patients suffer from moderate to severe post operative pain despite recent improvements in pain treatment. Severe pain is associated with decreased patient satisfaction, delayed post operative ambulation, the development of chronic or persistent post operative pain, increased incidence of pulmonary and cardiac complications, and increased morbidity and mortality (Ghoneim & O’Hara, 2016).

Chronic or persistent post surgical pain is a serious clinical problem. It is a common reason for early retirement and unemployment and represents an extensive drain on societies’ resources. The factors that seem to affect its incidence include the extent of preoperative pain, trauma during surgery, and anxiety and depression. Cancer patients seem particularly susceptible (Ghoneim & O’Hara, 2016).

In a systematic review of the psychosocial predictors and correlates for chronic post surgical pain, depression was a strong predictor. Comorbidity of pain and depression provokes worsening of both conditions. It is important therefore to identify patients at high risk for its development and optimize their management (Ghoneim & O’Hara, 2016).

Chronic, persistent post surgical pain influences patients’ quality of life (even after minor surgical procedures) and is currently regarded as an important outcome reflecting the quality of perioperative care provided to patients. A recent study just confirmed that moderate-to-severe persistent post surgical pain is common after outpatient surgery (ie, ambulatory and short-stay procedures), and inguinal hernia repair is a very common surgical procedure, often performed on an ambulatory base (Bugada et al., 2016).

Among risk factors for persistent post surgical pain development, the severity of acute post operative pain is often mentioned, which implies that individuals prone to suffer intense post operative pain may be the most vulnerable to persistent post surgical pain. However, not every patient with severe post operative pain will later develop persistent post surgical pain (Bugada et al., 2016).

To identify the scope of a person’s pain following surgery, especially pain persisting more than 2 to 3 months after surgery, a careful clinical evaluation is needed. This includes history, physical examination, and appropriate special tests in order to identify or exclude reversible underlying conditions (Gilron & Kehlet, 2014). Be aware of risk of persistent pain following surgery in the following instances:

- If the patient was previously pain free but has now developed a new chronic pain syndrome

- If previous pain at the site of surgery still remains

- If the patient previously suffered from a chronic pain syndrome—unrelated to the surgery—and the pain persists (Gilron & Kehlet, 2014)

Pain in the ICU

Most, if not all, patients in intensive care units (ICUs) will experience pain at some point during their ICU stay. Pain can be related to injury, surgery, burns, or comorbidities, such as cancer, or from procedures performed for diagnostic or treatment purposes. Some patients may even experience substantial pain at rest. Despite increased attention to assessment and pain management, pain remains a significant problem for ICU patients (Kyranou & Puntillo, 2012).

Unrelieved pain in adult ICU patients is far from benign. Medical and surgical ICU patients who recalled pain and other traumatic situations while in the ICU had a higher incidence of chronic pain and post traumatic stress disorder symptoms than did a comparative group of ICU patients. Concurrent or past pain may be the greatest risk factor for development of chronic pain (Kyranou & Puntillo, 2012).

Pain Associated with Cancer

Pain occurs in 20% to 50% of patients with cancer (NCI, 2016). It is one of the most severe, feared, and common symptoms of a variety of cancers and is a primary determinant of the poor quality of life in cancer patients (Bali et al., 2013). Cancer-associated pain—particularly neuropathic pain—has been shown to be resistant to conventional therapeutics whose application may be severely limited due to widespread side effects (Bali et al., 2013).

Pain from cancer tends to increase in severity as the cancer advances, and patients often experience pain at multiple sites concurrently. The highest prevalence of severe pain occurs in adult patients with advanced cancer. There may be multiple mechanisms with distinct patterns, such as continuous pain, movement-related pain, and spontaneous breakthrough pain.

As cancer reaches the advanced stage, moderate to severe pain affects roughly 80% of patients. Younger patients are more likely to experience cancer pain and pain flares than are older patients (NCI, 2016).

Research from Europe, Asia, Australia, and the United States indicates that cancer patients are repeatedly undertreated for pain, both as inpatients and outpatients—sometimes receiving no analgesia at all. Regardless of what stage the cancer has reached, it is necessary to determine the prevalence of pain in specific cancer types, both to raise awareness among clinicians and to improve patient management (Kuo et al., 2011).

Classifying Cancer Pain

Classifying cancer pain can be a challenge because the pain often does not have a single cause. Pain can be acute or chronic and can vary in intensity over time. Acute pain is typically induced by tissue injury and diminishes over time as the tissue heals. Chronic pain persists after an injury has healed or becomes recurrent over months; or results from lesions unlikely to regress or heal (NCI, 2016). Tumors, which occupy space, can also cause pain by pressing on skin, nerves, bones, and organs.

Breakthrough pain is common in cancer patients. It is a temporary increase or flare of pain that occurs in the setting of relatively well-controlled acute or chronic pain. Incident pain is a type of breakthrough pain related to certain activities or factors such as vertebral body pain from metastatic disease. Breakthrough and incident pain are often difficult to treat effectively because of their episodic nature. In one study, 75% of patients experienced breakthrough pain; 30% of this pain was incidental, 26% was non-incidental, 16% was caused by end-of-dose failure, and the rest had mixed etiologies (NCI, 2016).

Pain can be a side-effect of therapies used to treat cancer. A systematic review of the literature identified reports of pain occurring in 59% of patients receiving anti-cancer treatment and in 33% of patients after curative treatments (NCI, 2016). Some pain syndromes that can be caused by cancer therapies include:

- Infusion-related pain syndromes (venous spasm, chemical phlebitis, vesicant extravasation, and anthracycline-associated flare)

- Treatment-related mucositis

- Chemotherapy-related musculoskeletal pain (diffuse arthralgias and myalgias in 10% to 20% of patients)

- Dermatologic complications and chemotherapy (acute herpetic neuralgia, tingling or burning in their palms and soles, rash)

- Pain from supportive care therapies (osteonecrosis, avascular necrosis)

- Radiation-induced pain (mucositis, mucosal inflammation in areas receiving radiation, pain flares, and radiation dermatitis) (NCI, 2016)

The Pain Ladder

Although cancer pain or other symptoms often cannot be entirely eliminated, available therapies can effectively relieve pain in most patients. Good pain management improves a patient’s quality of life throughout all stages of the disease. Patients with advanced cancer may experience multiple concurrent symptoms with pain. In these patients, a thorough assessment of symptoms and appropriate management is needed for optimal quality of life (NCI, 2016).

The Pain Ladder was developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) in the context of cancer care. The WHO three-step analgesic ladder presents a stepped approach based on pain severity. If the pain is mild, begin with Step 1. This involves the use of analgesics such as acetaminophen or an NSAID, while keeping in mind potential renal and gastrointestinal adverse effects (WHO, 2016).

If pain persists or worsens despite appropriate dose increases, a change to a Step 2 or Step 3 analgesic is indicated. Most patients with cancer pain will require a Step 2 or Step 3 analgesic. Step 1 can be skipped in favor of Step 2 or Step 3 in patients presenting at the onset with moderate-to-severe pain. At each step, an adjuvant drug or modality such as radiation therapy may be considered in selected patients. World Health Organization recommendations are based on worldwide availability of drugs and not strictly on pharmacology (WHO, 2016).

In general, analgesics should be given “by mouth, by the clock, by the ladder, and for the individual” and should include regular scheduling of the analgesic, not just on an as-needed basis. In addition, rescue doses for breakthrough pain should be added. The oral route is preferred as long as a patient is able to swallow. Each analgesic regimen should be adjusted for the patient’s individual circumstances and physical condition (NCI, 2013).

World Health Organization Analgesic Ladder

Source: Adapted from WHO, 1986. Used with permission.

Clinical management of cancer pain is complex, driven by patient’s response, and the need to have both shorter and longer acting preparations and equi-analgesic dose ratios. The process of combining or switching opioids is complex for the clinician, who must understand the different half-life, receptors, and conversion ratios of these opioids, which can vary greatly among individuals, opioids, and even by opioid dose (Gao et al., 2014).

Adjuvants medications can enhance the analgesic effect of opioid drugs in patients with cancer. Concurrent use of adjuvants is recommended by the World Health Organization and has been recognized as one of the effective strategies in improving the balance between analgesia and side effects. However, consistent evidence suggests an under-utilization of adjuvants in cancer pain management, which may contribute to unnecessary opioid switching or rotation (Gao et al., 2014).

Pain Associated with Arthritis

Arthritis and other rheumatic conditions are a leading cause of disability in adults in the United States. The negative consequences of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions, including pain, reduced physical ability, depression, and reduced quality of life, can impact the physical functioning and psychological well-being of those living with the conditions (Schoffman et al., 2013).

Treatment of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions is costly, and given the growing number of people in the United States over the age of 65, arthritis and other rheumatic conditions are expected to be a large burden on the healthcare system in the coming years. The number of Americans with arthritis and other rheumatic conditions is expected to reach about 67 million by 2030, meaning that 25% of Americans will have arthritis and other rheumatic conditions (Schoffman et al., 2013).

Osteoarthritis

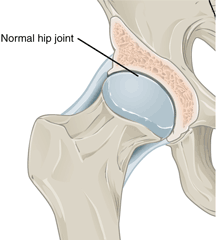

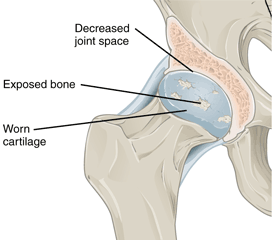

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a joint disorder, characterized by degeneration of joint cartilage. It causes joint pain and stiffness that worsens over time. OA is the most common form of arthritis and affects close to 27 million Americans. After the age of 65, 60% of men and 70% of women experience OA (Van Liew et al., 2013).

In a healthy joint, the ends of bones are encased in smooth cartilage. They are protected by a joint capsule lined with a synovial membrane that produces synovial fluid. The capsule and fluid protect the cartilage, muscles, and connective tissues. With osteoarthritis, the cartilage becomes worn away. Spurs grow out from the edge of the bone, and synovial fluid increases, causing stiffness and pain (NIAMS, 2015).

Hip Joint Showing Osteoarthritis Progression

Left: Normal hip joint. Right: Hip joint with osteoarthritis. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Osteoarthritis most often occurs in the hands (at the ends of the fingers and thumbs), spine (neck and lower back), knees, and hips. Source: NIAMS, 2015.

Although the prevalence of osteoarthritis increases with age, younger people can also develop it, usually as the result of a joint injury, a joint malformation, or a genetic defect in joint cartilage. Before age 45, more men than women have osteoarthritis; after age 45, it is more common in women. OA is more likely to occur in people who are overweight and in those with jobs that stress particular joints. The joints most commonly affected by OA are those at the ends of the fingers, thumbs, neck, lower back, knees, and hips (NIAMS, 2015).

Best practice guidelines for chronic osteoarthritis focus on self-management: weight control, physical activity, and pharmacologic support for inflammation and pain. Although low-grade inflammation underlies chronic osteoarthritis, it has not been a focus of best practice guidelines, particularly of its nonpharmacologic management. Obesity is an independent risk factor for osteoarthritis and there is an interactive relationship among osteoarthritis, obesity, and physical inactivity. Although the mechanisms for this association are not completely understood, biomechanical loading and metabolic inflammation associated with excess adipose tissue and lipids may have a role (Dean & Hansen, 2012).

Pain associated with osteoarthritis can lead to decreased physical activity, which is an independent risk factor for inflammation, likely due to the reduced expression of anti-inflammatory mediators. Physical inactivity also reduces daily energy expenditure and promotes weight gain (Dean & Hansen, 2012).

Approximately 80% of adults with OA have some movement limitations that affect daily activities; this is related to reduced quality of life and lower self-confidence. Having high levels of self-confidence is associated with higher quality of life, decreased pain, and increased activity for all people including those with OA (Van Liew et al., 2013).

Physical exercise is widely recommended for individuals with OA. A meta-analysis on treatments for OA found that exercise programs reduced pain, improved physical functioning, and enhanced quality of life among individuals with OA (Van Liew et al., 2013). Despite this, close to 44% of adults with arthritis report not engaging in exercise.

Psychological distress is an important factor associated with exercise and quality of life among people with OA. Evidence suggests that anxiety and depression lead to reduced functioning and to lower levels of physical activity. Although depression may pose barriers to activity engagement, physical activity has been shown to improve its symptoms and is a common focus of behavioral therapies. Conversely, improvements in depression are also likely to lead to increases in activity levels and quality of life (Van Liew et al., 2013).

Rheumatoid Arthritis

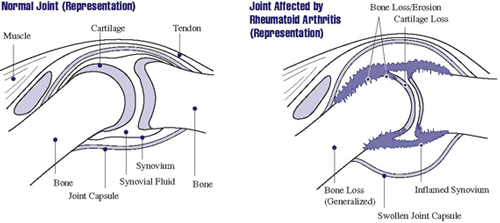

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is among the most disabling forms of arthritis and it affects about 1% of the U.S. adult population (about 2 million people). RA is an autoimmune disease that involves inflammation of the synovium, a thin layer of tissue lining the joint space. As the disease worsens, there is a progressive erosion of bone, leading to misalignment of the affected joint, loss of function, and disability. Rheumatoid arthritis tends to affect the small joints of the hands and feet in a symmetric pattern, but other joint patterns are often seen.

Because of its systemic pro-inflammatory state, RA can damage virtually any extra-articular tissue. Cardiovascular disease is considered an extra-articular manifestation and a major predictor of poor prognosis. Traditional risk factors such as obesity, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, hypertension, physical inactivity, advanced age, male gender, family history of cardiovascular disease, hyperhomocysteinemia, and tobacco use have been associated with cardiovascular disease in RA patients. In fact, seropositive RA may, like diabetes, act as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (Sarmiento-Monroy et al., 2012).

Joint Affected by Rheumatoid Arthritis

In rheumatoid arthritis, the synovium becomes inflamed, causing warmth, redness, swelling, and pain. As the disease progresses, the inflamed synovium invades and damages the cartilage and bone of the joint. Surrounding muscles, ligaments, and tendons become weakened. Rheumatoid arthritis can also cause more generalized bone loss that may lead to osteoporosis (fragile bones that are prone to fracture). Source: NIAMS, 2016.

Women are nearly three times more likely than men to develop rheumatoid arthritis—it can start at any age (mean age at the onset is 40 to 60 years). The precise cause of rheumatoid arthritis is unknown; like other autoimmune diseases it arises from a variable combination of genetic susceptibility, environmental factors, and the inappropriate activation of the immune responses. Multiple genes are associated with disease susceptibility, with the HLA locus accounting for 30% to 50% of the overall genetic risk (Fattahi & Mirshafiey, 2012).

Despite the well-documented negative impact of chronic pain on quality of life and functional outcomes, the best way to measure pain in patients with RA has not been adequately studied. Most research on the measurement of pain in RA focuses on the reliability of measures rather than their utility in predicting the course of illness. Therefore, there is little evidence to help guide clinicians and researchers on how best to assess RA pain with a focus on treatment and intervention in patients who are most likely to have impaired function over time (Santiago et al., 2016).

Studies that explore the role of pain as a predictor of functional disability typically focus on concurrent pain, or treat pain as a variable when examining predictors of future function. Since factors other than pain are the main predictors of interest, these studies fail to fully characterize the association of pain with future function and, more important, do not explore how different measures of pain and the time periods they reference may impact results (Santiago et al., 2016).

In the context of clinical trials for pain in general, the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) recommendations outline pain intensity as one key outcome measure, recommending primarily the use of a 0 to 10 numerical scale for rating pain. Recommendations also suggest use of a verbal rating scale that may be easier for some patients to complete (Santiago et al., 2016).

Psoriatic Arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is an inflammatory joint disease characterized by stiffness, pain, swelling, and tenderness of the joints as well as the surrounding ligaments and tendons. It affects men and women equally, typically presents at the age of 30 to 50 years, and is associated with psoriasis in approximately 25% of patients. Cutaneous disease usually precedes the onset of psoriatic arthritis by an average of 10 years in the majority of patients but 14% to 21% of patients with psoriatic arthritis develop symptoms of arthritis prior to the development of skin disease. The presentation is variable and can range from a mild, nondestructive arthritis to a severe, debilitating, erosive joint disease (Lloyd et al., 2012).

Psoriatic arthritis affects fewer people in the United States than rheumatoid arthritis. It has a highly variable presentation, which generally involves pain and inflammation in joints and progressive joint involvement and damage. There are multiple clinical subsets of psoriatic arthritis:

- Monoarthritis of the large joints

- Distal interphalangeal arthritis

- Spondyloarthritis, or a symmetrical deforming polyarthropathy similar to that of rheumatoid arthritis (Lloyd et al., 2012)

Left untreated, a proportion of patients may develop persistent inflammation with deforming progressive joint damage which leads to severe physical limitation and disability (Lloyd et al., 2012).

In many patients articular patterns change or overlap in time. Enthesitis (an inflammation of the area where tendons, ligaments, joint capsules, or fascia attach to bone) may occur at any site, but more commonly at the insertion sites of the plantar fascia, the Achilles tendons, and ligamentous attachments to the ribs, spine, and pelvis (Lloyd et al., 2012).

Dactylitis, an important feature of psoriatic arthritis, is a combination of enthesitis of the tendons and ligaments and synovitis involving all joints in the digit. The severity of the skin and joint disease frequently does not correlate with each other. Other manifestations of psoriatic arthritis include conjunctivitis, iritis, and urethritis (Lloyd et al., 2012).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs help with symptomatic relief, but they do not alter the disease course or prevent disease progression. Intra-articular steroid injections can be used for symptomatic relief. Physical or occupational therapy may also be helpful in symptomatic relief (Lloyd et al., 2012).

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs are the mainstay of treatment for patients suffering from psoriatic arthritis. Currently, the most effective class of therapeutic agents for treating psoriatic arthritis is the TNF-α inhibitors; however, these drugs show a 30% to 40% primary failure rate in both randomized clinical trials and registry-based longitudinal studies (Lloyd et al., 2012).