Blood flows from the heart to the brain via two large arterial systems: the carotid and the vertebrobasilar arterial systems. The vast majority of strokes—both ischemic and hemorrhagic—occur in the part of the brain supplied by the carotid circulation, which channels blood to most of the cerebral hemispheres.

The middle cerebral artery, the anterior cerebral artery, and the ophthalmic artery are the three clinically important branches of the carotid circulation. The middle cerebral artery supplies blood to the lateral part of the cerebral cortex, to most of the basal ganglia, and parts of the internal capsule. At the base of the brain, the carotid and vertebrobasilar arteries form a circle of communicating arteries known as the circle of Willis.

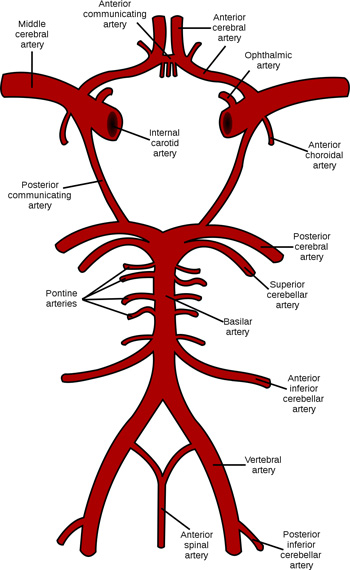

The Circle of Willis

Schematic representation of the circle of Willis showing the arteries of the brain and brain stem. Source: Wikimedia Commons. Used with permission.

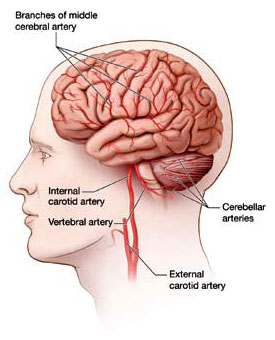

Carotid and Vertebral Arteries

The carotid and vertebral arteries ascend through the neck and divide into branches that supply blood to different parts of the brain. Source: NINDS, Stroke Challenge Brochure, p. 18.

Anterior Cerebral Artery

Medial surface of the brain showing the areas perfused by the anterior cerebral artery. Source: Lauren Robertson. Used by permission.

The middle cerebral artery, which supplies blood to the lateral surface of each hemisphere, is the largest of the cerebral arteries and the most common artery involved with stroke; embolism is the most common cause of blockage (Slater, 2014). Men are affected by middle cerebral artery stroke more often than women at a male-to-female ratio of 3 to 1 (Slater, 2014).

Because the middle cerebral artery is the area most commonly affected by ischemic stroke, its symptoms are the most familiar to healthcare providers: contralateral weakness and sensory loss in the face, neck, and arm (and to a lesser degree in the leg) and homonymous hemianopsia (loss of half of the visual fields of both eyes), as well as cognitive deficits that affect speech, language, and comprehension.

The anterior cerebral artery supplies the medial surfaceof the brain, and the ophthalmic artery supplies blood to the eye and adjacent structures of the face. Deep branches from the carotid system also supply blood to the regions of the brain below the cerebral cortex—the basal ganglia and the thalamus, together sometimes referred to as the extrapyramidal system, as noted earlier.

Blood traveling through the two vertebral arteries joins at the level of the brainstem to form the basilar artery. The vertebrobasilar artery supplies blood to the posterior part of the cerebral hemispheres, including the occipital lobes and the posterior portions of the temporal lobes, the cerebellum, and the brainstem. This is referred to as the vertebrobasilar or posterior circulation.

Carotid (Anterior) Circulation Disorders

[For more on this topic, see Module 15, Cognitive changes after a Stroke.]

Neurology’s favorite word is “deficit,” denoting an impairment or incapacity of neurological function: loss of speech, loss of language, loss of memory, loss of vision, loss of dexterity, loss of identity, and myriad other lacks and losses of specific function (or faculties). For all of these dysfunctions (another favorite term), we have privative words of every sort—aphonia, aphemia, aphasia, alexia, apraxia, agnosia, ataxia—a word for every specific neural or mental function of which patients, through disease or injury, or failure to develop, may find themselves partly or wholly deprived.

Oliver Sachs

The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat

A stroke in any of the major arteries within the carotid circulation (middle cerebral, anterior cerebral, and ophthalmic artery) disrupts higher cognitive, motor, and sensory processing. The most common problems—aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, and hemi-neglect, and other cognitive losses—occur in the areas of the brain supplied by the middle cerebral artery. Similar problems can occur with occlusions of the anterior cerebral artery, in which case the lower extremities and proximal upper extremities are more affected.

A stroke occurring as a result of a blockage in the middle cerebral artery on the left side of the brain can lead to a type of language impairment called aphasia. There are different types of aphasia, which are typically defined by the region of the brain that has been damaged.

Wernicke’s aphasia is caused by damage to the lateral surface of the left temporal lobe. It is sometimes referred to as receptive or fluent aphasia because a patient’s is fluent but the words carry no meaning. Sentences can be long and meandering—usually longer than seven words.

Areas Related to Broca’s and Wernicke’s Aphasia

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Broca’s aphasia is caused by damage to the lateral surface of the left frontal lobe. It is sometimes referred to as expressive or non-fluent aphasia because a patient is unable to communicate and sentences are short and choppy—usually less than seven words. Global aphasia is a combination of Wernicke’s and Broca’s aphasia in which a person is unable to understand the spoken word or communicate with speech. A severe stroke may begin with global deficits then slowly resolve to a lesser deficit.

If damage occurs on the right side of the brain, speech and comprehension are usually unaffected but other high-level cognitive deficits occur, including behavioral changes, general confusion and disinhibition, unintentional fabrication of information, memory deficits, attentional deficits, apraxia, and neglect.

Apraxia is another common cognitive problem caused by damage from a stroke in the carotid circulation. Apraxia is the loss of the ability to organize a movement or perform a purposeful act. It is a disorder of the execution of movement that cannot be attributed to weakness, incoordination, sensory loss, poor language comprehension, or attention deficit. Apraxia is a weakening of the top-down formulation of an action—the inability to sustain the intent to complete a movement. As a result, the nervous system is easily influenced by irrelevant input—a sort of pathologic absent-mindedness.

Apraxia affects all modalities including speech, writing, gesturing, dressing, and all activities of daily living (ADLs). It is difficult to for caregivers to understand and identify. Examples of apraxia are: picking up a telephone and beginning to talk without dialing, lighting a candle and trying to smoke it as if it were a cigarette, using a knife to brush one’s hair, using a pencil to butter bread. In all these examples the brain commands the body to perform a movement but the command fades before the movement is completed. The patient tries to complete the movement but has already forgotten what the task was. Nevertheless, an attempt is made to complete the task—perhaps by guessing.

A Stroke Patient’s Experience

Barbara is a 73-year-old woman who recently had a stroke and is in the rehabilitation unit of a large nursing home. She has been diagnosed with severe apraxia but has no weakness or trouble with her mobility. She is sitting at the side of the bed and, with the help of a nursing assistant, is trying to get dressed. She picks up a sock and moves to put the sock on her right foot. Instead, she places the sock next to the phone. The nursing assistant, in a hurry, hands the sock back to Barbara and tells her to finish getting dressed. Barbara again moves to put the sock on her right foot but slips it over her right hand. The nursing assistant grabs the sock and puts it on Barbara’s foot, thinking Barbara is being intentionally uncooperative. After she gets Barbara dressed, the nursing assistant reports to the charge nurse that Barbara is uncooperative and refused to get dressed.

In fact, Barbara is not being uncooperative or refusing to follow instructions. She wants to do what she is asked but can’t seem to remember how to do anything. Unfortunately, her apraxia will show up in every activity she attempts—from eating to bathing to dressing. If the nursing assistant understood the nature of Barbara’s difficulties she could ask for help in dealing with apraxia. The most obvious tactic is to break tasks down for Barbara and understand that she very quickly forgets what she is trying to do. Lots of verbal reinforcement and patience is needed to help Barbara complete her daily activities.

Agnosia is a sensory disorder in which a person is unable to recognize an object by sight, touch, or hearing in the absence of defects in the sensory apparatus of these systems. The person can touch, hear, and see but cannot recognize or identify the object. Agnosia is usually tested by asking a person to identify a series of objects that are placed out of sight in a bag or behind a partition. The person with agnosia will be unable to name an object by touch alone but will be able to identify the object using vision.

Anosognosia (hemi-neglect) is a sensory disorder caused by damage to the parietal lobe in which a person is unaware of the contralateral (opposite) side of the body including half of the visual field. It causes a disruption of a person’s body schema and spatial orientation and affects balance and safety awareness. The person is often unaware that the second half of the body exists and will deny that anything is wrong. Those with hemi-neglect may ignore food on the left side of a plate, walk into objects in the left half of the visual field, and completely ignore the left extremities. They may even claim that the affected arm or leg belongs to another person.

A stroke in the ACA circulation affects the medial surface of the brain. It can cause contralateral weakness and sensory loss, primarily in the leg. There may be some weakness in the contralateral arm, especially proximally. It affects the lower extremities more than the upper extremities, leading to difficulties with balance, gait, and mobility. Behavioral disturbances and confusion may be present, and urinary incontinence is not uncommon.

A small clot (microembolus) in the ophthalmic artery, the first branch of the internal carotid artery, can cause partial or complete loss of vision in one eye lasting seconds to minutes; this is called temporary monocular blindness or amaurosis fugax (fleeting blindness). It is caused by temporary loss of blood flow to the retina and can be a sign of an impending stroke. It is often described as a gray or black shade that comes down over the eye or as blurring, fogging, or dimming of vision. A clot lodged in the ophthalmicartery can also lead to a sudden and brief bilateral symmetric loss of vision in half of the visual fields that is called homonymous hemianopsia.

Loss of Visual Fields in Homonymous Hemianopsia

Paris as seen with right homonymous hemianopsia. The right visual field is missing in both eyes. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Thalamic Disorders

After a stroke affecting the thalamus, a person may become hypersensitive to pain. This syndrome, called thalamic pain or “central pain syndrome,” is due to damage to the spinal tracts that carry pain and temperature sensation from the periphery to the thalamus. Damage to these tracts, called the spinothalamic or trigeminothalamic tracts result in severe, spontaneous pain in the parts of the body connected to the damaged tracts. Thalamic pain starts several weeks after the stroke and presents as an intense burning pain on the side of the body affected by the stroke; it is often worsened by cutaneous stimulation.

Pain is typically constant, may be moderate to severe in intensity, and is often made worse by touch, movement, emotions, and temperature changes, usually cold temperatures. One or more types of pain sensations may be present—the most prominent being burning. Mingled with the burning may be sensations of pins and needles; pressing, lacerating, or aching pain; and brief, intolerable bursts of sharp pain similar to the pain caused by a dental probe on an exposed nerve. Individuals may have numbness in the areas affected by the pain. The burning and loss of touch sensations are usually most severe on the distant parts of the body, such as the feet or hands.

Basal Ganglia Disorders

In addition to the lateral surface of the cerebral cortex, the middle cerebral artery also supplies blood to the basal ganglia. A stroke affecting the basal ganglia usually causes motor control problems rather than hemiparesis. Damage typically causes too much movement (hyperkinesia) or too little movement (hypokinesia).

Hyperkinesia

What then is the opposite of deficit—an excess or superabundance of function? Neurology has no word for this—because it has no concept. A function, or functional system, works—or it does not; these are the only possibilities it allows. Thus a disease which is “ebullient” or “productive” in character challenges the basic mechanistic concepts of neurology, and this is doubtless one reason why such disorders—common, important, and intriguing as they are—never have received the attention they deserve. And this alone suggests that our basic concept or vision of the nervous system—as a sort of machine or computer—is radically inadequate, and needs to be supplemented by concepts more dynamic, more alive.

Oliver Sachs

The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat

Hyperkinesia is too much movement, and although our understanding of its cause may be unclear, we have many words to describe such disorders. Chorea is a hyperkinetic movement disorder characterized by arrhythmic, rapid, involuntary movement that flows from one part of the body to another. The most common type of non-drug-related chorea is Huntington’s chorea. Dystonia is a hyperkinetic movement disorder characterized by involuntary movement that is twisting, sustained, and repetitive. Over time, the affected body part may assume a fixed posture involving one joint (focal dystonia), two joints (segmental dystonia), or several joints (generalized dystonia).

Athetosis is a hyperkinetic movement disorder characterized by spontaneous writhing movements of the hand, arm, neck, or face. Tardive dyskinesia is a slow-onset, drug-induced hyperkinetic movement disorder characterized by rhythmic, unwanted movements of the face and extremities such as facial grimacing, tongue movements, and pill-rolling motions with the fingers. Tourette syndrome is characterized by excessive energy, tics, jerks, verbal noises, compulsive behavior, and grimaces. It is also associated with other behavioral disorders such as attention deficit disorder.

Hypokinesia

Hypokinesis is too little movement. Parkinson’s disease (paralysis agitans) is one of the most common hypokinetic movement disorders and is characterized by resting tremor, rigidity, masked faces, bradykinesia, and festinating gait. Parkinson’s disease is caused by widespread destruction of a portion of the brainstem (the substantia nigra), which is responsible for sending dopamine to the basal ganglia. Although Parkinson’s disease is not caused by stroke it is mentioned here as an example of a hypokinetic movement disorder.

Vertebrobasilar (Posterior) Circulation Disorders

Recall that the vertebrobasilar artery supplies blood to the posterior part of the cerebral hemispheres, including the occipital lobes and the posterior portions of the temporal lobes, the cerebellum, and the brainstem. Posterior circulation ischemia causes a variety of symptoms that are distinctly different from those found with carotid artery strokes. If the damage is in the area of the brainstem there may be loss of brainstem function, cranial nerve abnormalities (with or without hemiparesis), or hemi-sensory deficits.

If damage is in the area of the cerebellum, you can expect to see ataxia, intention tremor, and hypotonia. Ataxia is motor incoordination due to irregularities in the timing, rate, and force of a muscular contraction. Ataxia causes unsteady, grossly uncoordinated, or “drunken” gait, loss of balance, and a tendency to fall. It also affects the ability to judge the distance or scale of a movement, typified by overshooting or undershooting an object (dysmetria). As a result, vertigo, nausea, vomiting, and nystagmus are common occurrences following a cerebellar stroke.

Intention or action tremor is another common type of abnormal movement associated with cerebellar damage. The tremor is not present at rest (as with Parkinson’s) but occurs as soon as a movement is initiated. For example, a person may reach for a glass of water but be unable to control the force and range of the movement, especially at the end of the movement. While reaching for the glass the tremor increases and the individual may overshoot the glass entirely, touch the glass with too much force, or lift it too rapidly.

Hypotonia is a decreased resistance to the passive stretch of a joint. Muscles feel soft to the touch and lack normal tone. Hypotonia can be tested by tapping the patellar tendon reflex with a reflex hammer. A tap on the patellar tendon will normally produce a quick extension of the lower leg, which will come to rest after one or two swings. If cerebellar damage is present, a tap on the patellar tendon will cause the lower leg to oscillate 6 or 7 times before coming to rest. This is called a pendular swing and is typical of cerebellar damage.