[Material from this section is from CDC, 2005a.]

It was recommended that patients who met the criteria for potential SARS be admitted to the hospital when indicated. Close contacts and healthcare workers were encouraged to seek medical care for symptoms of respiratory illness.

Body Fluids

Respiratory Tract Specimens

Respiratory specimens were collected as soon as possible in the course of the illness. The likelihood of recovering most viruses diminishes markedly >72 hours after symptom onset. Some respiratory pathogens may be isolated after longer periods.

Three types of specimens were collected for viral or bacterial isolation and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing to identify the causative pathogen. These included:

- Nasopharyngeal wash/aspirates

- Nasopharyngeal swabs

- Oropharyngeal swabs

Nasopharyngeal aspirates were the specimen of choice for detection of respiratory viruses and the preferred collection method among children aged <2 years.

Blood Components

Acute serum specimens were collected and submitted as soon as possible. If the patient met the case definition, convalescent specimens were collected and submitted no sooner than 22 days after the onset of fever. Pediatric patients required a minimum of 1ml of whole blood for testing.

Stool

Stool (10–50 ml) was placed in a stool cup or urine container, capped securely, sealed and bagged. Specimens were then shipped with cold packs.

Tissue Specimens (postmortem)

Fixed

Fixed tissues (formalin fixed or paraffin embedded) from all major organs (e.g. lung, trachea, heart, spleen, liver, brain, kidney, adrenals) were stored and shipped at room temperature. Formalin fixed tissue was not considered a biohazard or chemical hazard.

Fresh Frozen

Fresh frozen tissues from lung and upper airway (e.g. trachea, bronchus) were collected aseptically as soon as possible after death. Technique and time impact risk of post-mortem contamination.

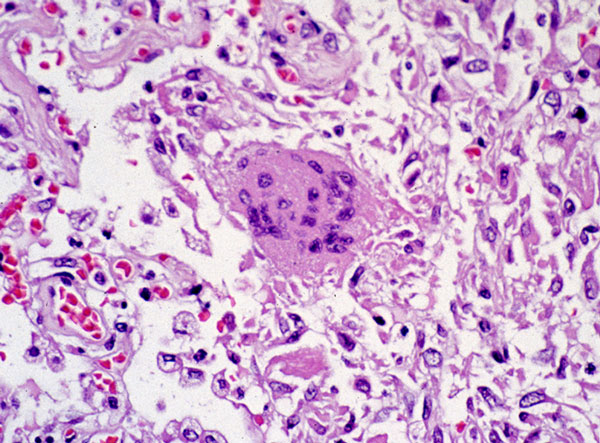

Frozen Section of Lung Tissue Infected with SARS

This photomicrograph reveals lung tissue pathology due to SARS. Source: CDC.

Radiologic Imaging

The radiology department at the Prince of Wales Hospital in Hong Kong issued a number of findings and recommendations for radiologic evaluation of people with suspected SARS infection.

The following radiologic imaging protocol was recommended:

- If SARS was clinically suspected, a chest x-ray was recommended.

- If the chest x-ray was abnormal, then no further imaging investigation was required other than serial x-rays for follow-up.

- If the chest x-ray was normal, a high-resolution CAT scan (HRCT) was performed. This could show changes 1 to 2 days before they became radiographically apparent.

According to hospital radiologists, peripheral/pleural–based opacity was sometimes the only abnormality in the early stages of disease and could range from ground-glass to consolidation in appearance. In suspected SARS cases with normal radiographs, the paraspinal region behind the heart was where lung lesions were frequently detected on HRCT.

Ground glass or consolidative opacification could affect large areas of the lungs in more advanced cases, especially in the lower zones and often bilaterally. Ground glass describes the appearance of partial filling of air spaces in the lungs with fluid. Lung consolidation occurs when the air that usually fills the small airways in the lungs is replaced with something else, such as pus or fluid (Healthline, 2020).

Calcification, cavitation, pleural effusion, and/or lymphadenopathy were not features of SARS.

High-Resolution CT (HRCT)

Computed Tomography examination was limited to HRCT only. Initially, conventional and high-resolution CT scans were performed on the thorax of all patients. With experience, it became apparent that pleural effusion or lymphadenopathy was not a feature of SARS.

The following features were found on HRCT in SARS patients at Prince of Wales Hospital and tended to occupy a sub-pleural position rather than axial:

- Solitary or multiple patchy area(s) of

- Ground-glass opacification

- Consolidation

- A combination of opacification and consolidation.

Reported Cases

On November 16, 2002, the first case of atypical pneumonia was reported in the Guangdong province in southern China. On March 24, 2003, CDC laboratory analysis suggested a new coronavirus may be the cause of SARS. It was thought that the SARS coronavirus jumped from bats to civets to people.

A five-year study of coronaviruses found in horseshoe bats that ended in 2017 was led by Ben Hu of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Wuhan, China. The researchers found SARS viruses in multiple species of horseshoe bats living in a single cave in Yunnan Province, China. In the study, they identified 11 new strains of the SARS virus and sequenced their full genomes to uncover their evolutionary relationships (Hu et al., 2017).

Although these SARS viruses were similar to the 2003 human SARS virus, they never found a virus that was exactly the same. They have hypothesized that genetic recombination occurred to create the SARS virus that caused the 2003 epidemic. The researchers also found other coronaviruses in the cave that are capable of being transmitted directly to humans from bats without an animal intermediary (Hu et al., 2017).