People who have Alzheimer’s or other dementias are themselves our best teachers about their needs and level of care. This course presents fifteen common sense guidelines based on what these individuals taught me over the twenty years I worked as a dementia care nurse.

Looking for Guidance

In the 1980s, when little was known about dementia and memory care units did not exist, we were hungry for knowledge about this fragile population. Standards of care for nurses and physicians had existed for a good many years. They combined usual practices with the minimal level of care needed for patients to have an optimal outcome (good quality of life and the ability to reach their highest level of functioning).

Then, in 1987, the Omnibus Reconciliation Budget Act (OBRA) published federal standards for nursing homes that are commonly referred to as OBRA-87 (Turnham, 2009). Those that did not comply by October 1990 were at risk for losing Medicaid reimbursements (Hawes et al., 1997). In order to judge the quality of the care given in nursing homes, surveyors looked to see if the facility met all of these standards.

For those residents with dementia who were in long-term care settings, however, the OBRA regulations fell far short of ensuring an optimal outcome. When this became obvious somewhere around 1990, interest grew in the creation of dementia care units, which evolved eventually to become memory care settings. Since that time, long-term care professionals have been struggling to understand the needs and behaviors of residents with dementia.

The provision of care for this population is more complex than for residents needing just physical care; cognitive decline requires an additional level of support. This includes care plans designed to preserve the skills for activities of daily living (ADLs) and additional provisions for the socialization, stimulation, and safety of residents who wander or cannot call for help when needed. Additional training for staff members was developed that includes the causes of dementia and what to expect in the various stages of the disease.

Good dementia care also includes the recognition that there can be major differences in each person residing on a dementia unit. The type of dementia, the stage of dementia—and even the fact that several different dementias may exist in an individual at the same time—can be an issue. Additionally, most people with dementia are elders who may be suffering from multiple chronic diseases.

Simply put, good dementia care must be flexible. Dementia is not a “one size fits all” disease. For this reason, I created guidelines—not rules—based on common sense. These guidelines go further to meet the needs of dementia patients than the OBRA regulations, which are inflexible and not directed at long-term care residents with cognitive disabilities.

Understanding Human Needs

People do not consist of memory alone. They have feeling, will, sensibility, moral being. It is here that you may touch them, and see a profound change.

Alexander Rossinovich Luria

Founder of Russian Neuropsychology

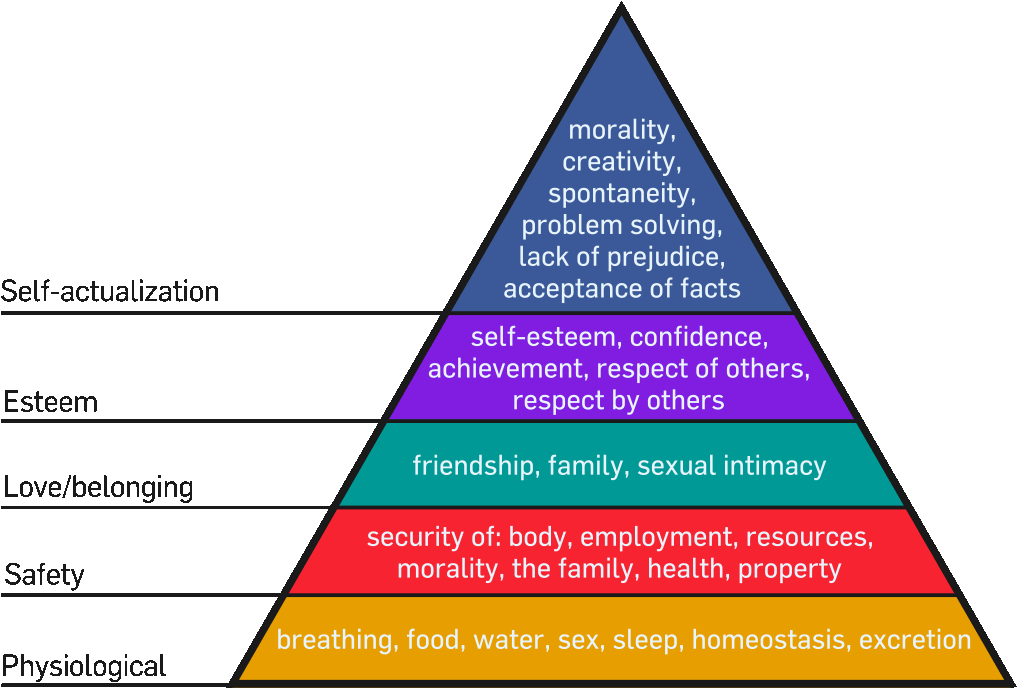

In 1943 Abraham Maslow introduced his hierarchy of needs as a framework to help us understand the stages of human development. Maslow laid out the stages in the shape of a pyramid (see below) to illustrate that we move successively from the base toward the top as our needs are met. We cannot progress if our basic needs (the base) are not met. Similarly, each level must be achieved before we can move higher in the pyramid.

The base of the pyramid shows that humans all have the same needs at birth; these include food, water, clothing, and shelter. Once bodily needs are met, we become concerned with safety. When we feel safe, we tend to seek love and a sense of belonging. Later, as we mature, we develop a need for respect and self-esteem. The top of Maslow’s pyramid represents self-actualization, the need to meet one’s potential. As human needs are successively met, self-actualization becomes the ultimate goal.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Source: Maslow, 1943; image from Wikipedia Commons.

It is often said that individuals suffering from dementia become more and more childlike as their disease progresses. This is wrong. While children are moving up the developmental pyramid, they gain experience where none existed before. People who have dementia are moving down the developmental pyramid as they lose memory of their life experiences. Even though they are declining, they are still adults with memories, experiences, and skills. What remains still affects who they are and how they relate to their families and caregivers.

Never Treat Adults As If They Are Children

Individuals who have dementia are not becoming childlike. Although they are losing memories, they remain adults and must be considered to be, and treated as, adults.

With each stage of dementia, major losses occur, and the caregiver must work to support and preserve the person’s skills as long as possible. Before dementia, a person filled many roles in life, and may have achieved—or come close to—their full potential. Dementia takes this away.

Despite these losses, families and dementia care staff have the ability to help trigger memories and bits of information. Even late-stage dementia patients have been known to experience moments of clarity, recognizing loved ones and remembering bits of information believed to have been erased by their disease.

As caregivers it would be helpful for us to imagine what it is like for the person with dementia to suffer so many losses and what it does to a person’s quality of life. Our ability to do this is the basis for common sense dementia care.

The Guidelines

Here are the guidelines that I have developed over my years of working with people who have Alzheimer’s or other dementias. Each one of them is explained further in its own module.

Guideline 1. Imagine yourself in the place of the person with dementia.

Guideline 2. Learn good dementia care communication skills.

Guideline 3. Do not argue with or say no to the person with dementia.

Guideline 4. Validate the feelings of the person with dementia.

Guideline 5. Consider the whole person, not just the dementia.

Guideline 6. Learn to use “feel goods.”

Guideline 7. Don’t use reality orientation except for early-stage dementia.

Guideline 8. Encourage independence.

Guideline 9. Arrange for appropriate activities.

Guideline 10. Everyone needs to love and be loved.

Guideline 11. We all need something important to do each day.

Guideline 12. Don’t be judgmental.

Guideline 13. Keep your sense of humor. Use it wisely.

Guideline 14. Religion is a comfort even for people with dementia.

Guideline 15. Expect the unexpected.

Try answering the boldfaced blue questions found in each of the modules. They are designed to help you engage more fully with the person who has dementia.