As the number of older Americans increases, so will the number of caregivers needed to provide care. . . .Currently, there are seven potential family caregivers per adult. By 2030 there will be only four potential family caregivers per adult.

CDC, 2019b

A caregiver is a person who provides direct care to another who requires assistance with everyday tasks to function in daily life. Care recipients can include children, people with disabling conditions, and older adults. Formal caregivers are members of a formal service system, whether paid or unpaid.

Informal (family) caregivers are “any relative, partner, friend or neighbor who has a significant personal relationship with, and provides a broad range of assistance” to the recipient . Informal caregivers can be primary or secondary caregivers and may or may not live with the recipient (FCA, 2014). Almost always unpaid, informal caregivers make up the vast majority of their cohort.

Family caregivers share certain responsibilities, challenges, and rewards regardless of the conditions or illnesses of their loved one but caregivers of patients with dementia face a number of additional challenges and potential stressors.

Nearly half of all caregivers of older adults do so for someone with Alzheimer’s or another dementia. While 1 in 5 caregivers of older adults reports a decline in their own health due to caregiving responsibilities, among those caring for someone with Alzheimer’s the proportion is 1 in 3 (CDC, 2019).

In 2017, 16 million family members and friends provided 18.4 billion hours of unpaid care to people with Alzheimer’s and other dementias, at an economic value of more than $232 billion. In just the next year those figures increased to more than 16 million family members, 18.5 billion hours, and $234 billion, respectively (CDC, 2019; AlzA, 2019b).

Approximately two-thirds of dementia caregivers are women, 34% are age 65 or older, and about 25% are also caring for children under age 18. Dementia caregivers provide care for a longer time period than do caregivers for those with other conditions—more than 50% provide care for 4 years or longer (CDC, 2019c).

As the population ages and the number of people with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias increases so too will the need for more caregivers (CDC, 2019b,d). Although some research suggests that in the United States and other higher-income Western countries the prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer’s has declined in the last 25 years, globally the total number of people with Alzheimer’s and related dementias is increasing. And low- and middle-income countries will bear the brunt (68%) of the projected increase in the global prevalence and burden of dementia by 2050. In those countries there is no evidence that the risk of Alzheimer’s and other dementias has been declining (AlzA, 2019b).

Estimating Future Caregiving

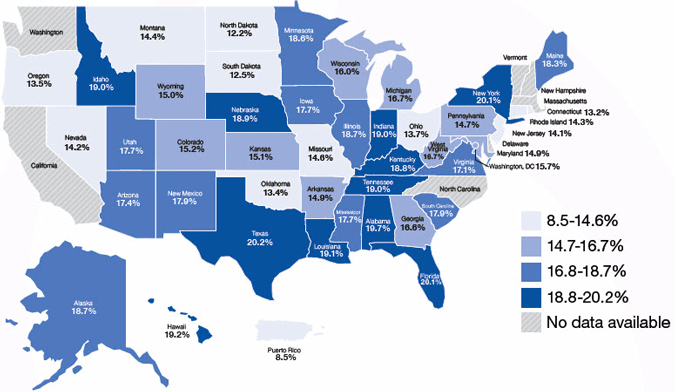

The map shows percentage rates for non-caregivers aged 45 years or older who expect to be caregivers within the next two years.

Source: CDC, 2019d.

Challenges and Rewards of Caregiving

Caregiving can be both challenging and rewarding, often at the same time. Caregiving can result in emotional stress, depression, and negative effects on employment, income, and financial security for caregivers. Yet, caregiving proves to be a rewarding experience for many and can bring family members closer together (CDC, 2019, 2019b,c; Robinson et al., 2019).

The challenges of caregiving for a person with Alzheimer’s or other dementia (ADRD) often include:

- Overwhelming emotions as the patient’s capabilities decrease

- Fatigue and exhaustion

- Isolation and loneliness

- Financial and work complications

While rewards for caregivers can include:

- Bonding with patient deepened through care, companionship, and service

- Improved problem-solving and relationship skills

- Formation of new relationships through support groups

- Unexpected rewards that develop through compassion and acceptance (Robinson et al, 2019)

Acquiring more knowledge about the disease and its expected progress can reduce caregiver frustration by allowing for planning and preparation supported by reasonable expectations. Information about disease progression is one of the things caregivers are most interested in receiving (Slaboda et al., 2018; Robinson, 2019).

For healthcare professionals who would like more statistics for themselves or to support action by or in their practice, facility, or community, the CDC provides broad access to data about caregivers and their situations, most recently from 2015–2017 through the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). Information is available for the United States as a whole, as well as by region and state, and reports can be generated and viewed through the Alzheimer’s Disease and Healthy Aging Data Portal (CDC, 2019d,e).

Caregiving and Public Health

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) notes public health can play an important role in supporting caregivers by helping to expand, promote, and tailor resources in these areas:

- Community-based programs for physical activity, chronic disease self-care, and caregiver education;

- Peer support groups and social gatherings for people affected by dementia;

- Online support and information resource centers;

- Apps for caregivers and persons living with dementia and GPS tracking devices;

- Home healthcare services and home modification programs;

- Adult day and respite care;

- Advanced care and advanced financial planning;

- Transportation services; and

- Information and referral services (CDC, 2019)

According to the Alzheimer’s Association, more and more communities in the United States are taking a public health approach to Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias because:

- The burden is large.

- The impact is major.

- There are ways to intervene. (AlzA, 2019)

The number of Americans living with Alzheimer’s is expected to grow, so that by 2050 there may be as many as 14 million living with the disease. The financial burden could exceed $1 trillion and two-thirds of that would be borne by federal and state governments through Medicaid and Medicare (AlzA, 2019).

While Alzheimer’s and other dementias are not preventable at this time, some impacts are. Research shows that more than one-quarter of all hospitalizations of people with dementia are preventable, and that 95% of those with Alzheimer’s and other dementias have another chronic condition like heart disease, diabetes, or stroke. The complications arising in management of this situation often result in poorer health outcomes and higher costs (AlzA, 2019).

The potential impacts of Alzheimer’s and other dementias can be mitigated with a strong public health response. This response can help support early detection and diagnosis, reduce risky health behaviors, collect and use surveillance data, develop workforce competencies, and mobilize community partnerships (AlzA, 2019).

The CDC and the Alzheimer’s Association have worked together to develop the Healthy Brain Initiative (HBI). The initiative’s guidebook—State and Local Public Health Partnerships to Address Dementia, the 2018–2023 Road Map—offers a detailed plan that state and local public health agencies and their partners can use. Many of the twenty-five actions in the Road Map can help meet the needs of caregivers, and it also promotes education and support for healthcare providers as they work with caregivers (AlzA, 2019; CDC, 2019).

The Road Map section entitled “Assure a Competent Workforce” includes:

- W-2 Ensure that health promotion and chronic disease interventions include messaging for healthcare providers that underscores the essential role of caregivers and the importance of maintaining their health and well-being.

- W-3 Educate public health professionals about the best available evidence on dementia (including detection) and dementia caregiving, the role of public health, and sources of information, tools, and assistance to support public health action.

- W-4 Foster continuing education to improve healthcare professionals’ ability and willingness to support early diagnoses and disclosure of dementia, provide effective care planning at all stages of dementia, offer counseling and referral, and engage caregivers, as appropriate, in care management.

- W-7 Educate healthcare professionals to be mindful of the health risks for caregivers, encourage caregivers’ use of available information and tools, and make referrals to supportive programs and services. (CDC, 2019)

It is critical that our perception of caregiving encompass the joint roles and importance of family caregivers and healthcare providers in working toward the best possible outcome for a patient. Research has demonstrated the critical value of training for both caregivers and healthcare providers.

Test Your Knowledge

Caregivers for patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias can include:

- Formal and informal (family) caregivers.

- Only formal caregivers working for an agency.

- Only informal (family) caregivers.

- Only healthcare providers.

Supporting caregivers is a public health concern because:

- The burden is large, the impact major, and intervention is impossible.

- The burden is large, the impact major, and intervention is possible.

- The burden is small, the impact major, and intervention is possible.

- The burden is large, the impact minor, and intervention is possible.

Answers: A,B